I.

I just went to take a picture of the detachable penis. Several factors motivated me. I’ll explain.

II.

It’s well-known that Mark David Chapman carried a copy of The Catcher in the Rye on the night he murdered John Lennon. Richard Halpern, in his sharp new study, Norman Rockwell: The Underside of Innocence (University of Chicago Press), reminds us of another, even weirder pop culture connection—one that literally brought Chapman to New York and infamy. To pay for the death trip (and the fatal firearm), “Chapman sold his beloved lithograph of Norman Rockwell’s Triple Self-Portrait for $7,500.” “I find it suggestive that one icon of innocence was used to fund the assassination of another,” Halpern writes.

A passionate Rockwell fan, Halpern (a Shakespeare scholar by trade) suggests that “under the guise of innocence,” the paintings “often present potentially disturbing materials that they then dare the viewer to see and recognize.” In other words, sex is everywhere. The sanitized, sentimental scenes—a description critics and partisans can agree on—reveal darker material under this close reading. (Biographer Laura Claridge has noted that Rockwell, once a patient of Erik Erikson’s, “had always developed his narrative line through… an almost classical, psychoanalytically oriented process of free association.”) Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter sports a strap-on. Christmas heralds sexual awakening. Dolls are disturbingly spread-eagled. In a dazzling deconstruction of 1955’s Art Critic (in which a snooty young painter stands before the portrait of an ample woman, peering at a piece of jewelry), Halpern not only highlights the real-life Oedipal tensions present (Rockwell’s wife Mary posed as the painted lady, and his son Jarvis, an aspiring artist, stood in as the museumgoer), but also compares the effete connoisseur’s hunched pose to that of Ingres’s famous Oedipus and the Sphinx.

III.

On a block of the Upper West Side, not far from the Hotel des Artistes, where Rockwell briefly lived (itself a little south of Lennon’s home, the Dakota), a fancy retail-condo building is going up. Over the summer, the boards surrounding the site bore a mural depicting what the shiny new block would look like, with tiny photo-realistic New Yorkers strolling around an antiseptically lit stretch of sidewalk. The first time

I saw it, pen-wielding wags had already struck. Energized by reading British graf god Banksy’s recent volume, Wall and Piece (Century), I took a closer look. The little people were saying things like, “I’m glad they tore down the florist’s to put up a new BANK!” and “Bank bank bank.” (The Upper West Side’s high rents have stimulated a surfeit of new bank branches.) Another artist had drawn crude, disembodied male members floating around some of the mouths—think of the graffito that adorns Carrie Bradshaw’s side-of-bus book ad in Sex and the City. These were little phalluses, instant and impotent and hilarious, going head-to-head with the still-developing big one behind the boards.

IV.

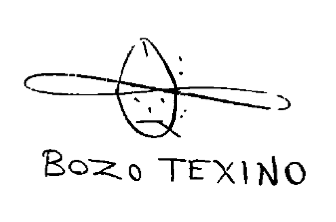

Who Is Bozo Texino?, Bill Daniel’s brief, evocative black-and-white doc (which recently screened at New York’s Anthology Film Archives), looks at the ancient American way of the hobo, and the distinct signatures these men leave on trains. The original, clean-lined “Bozo Texino” drawings, depicting a pipe-smoking dude in a ten-gallon hat, appeared on more than a quarter million boxcars, beginning in the ’20s. They were the work J. H. McKinley—not a hobo at all but an engine man for the MoPac line. Here was an interesting twist: a company man who couldn’t resist the urge to decorate/deface.

V.

McKinley died in 1967, so who was executing the drawings in the ’90s, when filmmaker Daniel first spotted them? The more recent iterations differ slightly from McKinley’s originals: a cigarette instead of a pipe; no Lone Star insignia on the hat, nor any shoulders; and, in a tantalizing twist, the brim now describes an infinity symbol.

VI.

Norman Rockwell’s middle name was Percevel, the odd spelling a link to his mother’s one illustrious ancestor. As a boy, Rockwell hated the name, which, as an already scrawny child, he saw as sissifying (according to friend Donald Walton’s 1978 A Rockwell Portrait). He disliked the name so much that he even deleted the initial from legal documents. He removed his P.

VII.

Sir Norman Percevel’s claim to fame: he was supposedly the man who caught protoanarchist Guy Fawkes trying to blow up parliament in 1605 (Walton’s account says “Tower of London”), and kicked him down the stairs.

VIII.

Triple Self-Portrait, the killer’s favorite, plays a delirious, Magrittean game of representation. The painting shows Rockwell with his back toward us, sitting at an easel (on which he’s tacked a slip of paper bearing small studies of himself), brush poised above an already quite detailed self-likeness. We see Rockwell’s reflection in the mirror he’s studying, a little to his left, but glare on his spectacles obliterates our view of his eyes. The painting he’s working on clearly does not have eyeglasses. This is a view of the infinite (imagine Rockwell qua Rockwell working on these three-plus Rockwells), and of the unreliable narrator.

IX.

Like Bozo Texino, this painted Rockwell smokes a pipe—in the mirror, in the “real” portrait of him as the self-portraitist, and in the eyeglassless depiction on canvas. Though he doesn’t wear a ten-gallon hat with a lemniscate brim, one of the Rockwells has headgear: an antique (Percevelian?) helmet is inexplicably perched on top of the easel.

X.

Back to Norman’s detachable P and the capture of Guy Fawkes: I find it suggestive that one icon of innocence has a nostalgic link to an icon of social disruption. This seems entirely in keeping with Halpern’s provocative Rockwell, who practices an art of disavowal in which unsettling forces dwell in the most innocuous of scenes. By suppressing Percevel—i.e., the man who suppressed the violent Fawkes—“Norman Rockwell” is not only masculinized, but a conduit for darker, disruptive elements.

XI.

One photo in Banksy’s Wall and Piece shows a spray-painted beefeater spray-painting the anarchy symbol on the side of a London building. With the Dark Rockwell, Banksy, and Bozo Texino on the brain, I thought it would be fun to revisit the scurrilous bits of Upper West Side graffiti I’d seen earlier. But when I arrived, the entire defaced mural had been replaced. There was a street scene, as before, and a larger-scale depiction of the interior of one of the posh units under construction. I studied the entire length of the boards. The futuristic minnikins uttered no criticism of the new building, nor were they in the company of primitive airborne wieners. It crossed my law-abiding mind that perhaps I might add my two cents to the illustration, but then I saw that a security guard had been installed.