Friday, April 7, 2006: poolside at the ancient Egypt–themed Luxor Hotel & Casino—the third-largest hotel on the planet—264 regional rock paper scissors champions and their guests are whipped to a frenzy by Too White Crew, a late-’80s/early-’90s tribute band promising “old school hip hop served hot with crackers.” The band composed a theme song for the USA Rock Paper Scissors League and now, Biz Markie and Tone Loc covers having set the mood, the crowd sings along with “Raise ’em Up”:

[Chorus (sung to the beat from House of Pain’s “Jump Around”)]:

Raise ’em up… throw your rocks up

Raise ’em up… throw your papers up

Raise ’em up… throw your scissors up…

[Sample Verse (sung in the style of your favorite Beastie Boy)]:

I’ve trained for years, I know all

the tricksStep inside my circle and take your licks

’Cause when you lay your sheet, the crowd will watch

Me cut you with scissors, and say, “Peace out, beeyotch”

After dropping “da bomb,” C-note, Professor Milk, the Fly Girls, and the rest of the Too White posse pose a not-so-rhetorical question, given the flailing audience of roshambo geeksters: “Are you ready to get your Bud Light on?” But in this demographically eccentric beer commercial come to life, the answer is always yes.

Over the past few years, competitive rock paper scissors leagues have been popping up around the country—mostly in bars, on college campuses, or in bars on college campuses. Anyone who’s played RPS, also known as roshambo, thinks they know the game: two combatants square off and deliver one of three legal throws—rock, paper, or scissors—where rock smashes scissors, scissors cuts paper, and paper covers rock. Street-style play calls for anything from a single-throw death match to a marathon best-of-five hundred series, but tournaments usually follow a format where the first player to win two best-of-three sets takes the match.

For the novice or the purely disinterested, the game never rises beyond the very superficial notion that rock paper scissors is a game of chance. “It’s just random,” the naysayer might say, perhaps just before making a dim-witted coin-toss comparison. But according to Douglas and Graham Walker, authors of The Official Rock Paper Scissors Strategy Guide, the differences could not be more striking: tossing a coin is by its very nature a passive act, simply letting fate take its course; but during the “Dance of Hands” that is rock paper scissors, the player actively influences the outcome not only by his choice of throws, but by the ability to interpret or ignore the signals provided by an opponent. Like poker, rock paper scissors involves “tells,” subtle body-language-based clues that can tip off a player’s intended throw.

While some players can track these tells over the course of a match (like the nervous twitching of fingers preceding a scissors toss), there’s a wealth of information that can be gleaned about an opponent before even stepping into the ring: Is he standing with shoulders slumped, staring down at his loafers? Do you suspect he still lives with his mother? This guy is textbook paper, so have your scissors locked and loaded, my friend. Is your adversary wearing a do rag or muscle T-shirt and prone to high fives? Chances are this douchebag is gonna favor rock, the most aggressive (and common) of the three throws. Finally, are you playing someone you once slept with, a filthy liar who won’t return your calls? Look out for scissors!—the go-to throw of devious bastards.

Beyond archetype recognition, advanced rock paper scissors players employ very specific psychological strategies, like baiting a throw via visual or verbal cues (masking a throw of paper as rock until the very last second, or simply yelling, “Here comes rock!”); some rely on probability to track tendencies and keep a mental tally of a challenger’s throws. One up-and-comer I spoke with at last spring’s 2006 USARPS League championships in Vegas claimed he slugged his way through two regional tournaments throwing nothing but paper. He dared more than a dozen competitors to call his bluff… and for a while, no one did.1

That’s the beauty of competitive RPS: layer upon layer of simplicity add up to something much more cerebral—if you open up your mind and let it go there. Drinking definitely helps, which explains why so many events happen where alcohol is readily served—and why major beer brands have replaced mining operations, paper mills, and office supply companies as the sport’s primary sponsors. But can rock paper scissors truly be considered a sport? Or, like when Garth Brooks released that record as Chris Gaines, is the semiseriousness being attached to RPS just another elaborate postmodern hoax?

Spend a few minutes with one who achieved the title of “master,” and it’s a short leap to start believing there’s something very real going on here. As Graham Walker, cofounder of the World Rock Paper Scissors Society (a rival to the USARPS League), says: “The game is simple. It’s the gamesmanship that makes it complex.” Think about it… Poker? Competitive eating? Cherry-pit spitting? Golf? These are marginal activities created to pass the time or sell advertising. But rock paper scissors is played around the world in different variations, has a real history as a conflict-resolution device, and its champions are as mentally disciplined as any professional athlete. It sure feels like a sport to me.

Today’s big-time tournaments feature trained referees and official rules (strictly forbidden are both the controversial “fourth throw” of dynamite,2 and the blatantly illegal vertical paper, or “the handshake”3), and have created legends like C. Urbanus (he of the Urbanus Defense, a strategy where one intentionally loses the first throw),4 and historic moments such as Pete Lovering’s 2002 “rock heard round the world.” For those of us whose life-or-death college decisions (like who had to clean the bong) hinged on rock paper scissors proficiency, the allure of competitive RPS is too strong to resist. But along with the pageantry, there’s a visceral energy that in part explains why so many are being drawn to the sport. Over the past few months, I’ve personally witnessed dozens of extended stalemates (identical throws that result in a tie), all of which made a marathon volley between Agassi and Sampras look like a game of patty-cake.5 While stalemates are infinitely exciting during street matches—my cousin claims he and a chum once tied twenty-seven straight times in a Rome back alley to determine who would get the last piece of a particularly delicious pizza—they are even more rousing under the bright lights as hundreds (or a handful) of spectators gaze on slack-jawed, punch-drunk with delight.

But how did this grand sport come to be? According to various sources, the origins can be traced to somewhere between pre–Homo sapiens (where it was called “rock-rock-rock”) and various ancient Asian cultures. The book Children’s Games in Street and Playground (Oxford University Press, 1969) by Iona and Peter Opie hypothesizes that RPS came to London by way of “Jan Ken Pon,” a Japanese game based on sansukumi: a nontransitive system where the snake fears the slug, the slug fears the frog, and the frog fears the snake.

Children’s Games also references a London traveler who discovered a version called “earwig man elephant” in Indonesia, as well as a scene in a tomb in Egypt that points to the existence of finger-flashing games as early as 2000 BCE. And the reason for the commonly used term roshambo? The most popular (but unsubstantiated) theory credits Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, also known as le comte de Rochambeau, the lieutentant general of the French forces during the American Revolution and the man thought to have first brought RPS to the United States.

*

Regardless of whether the weapon is rock, slug, or earwig, in modern times our brightest and least-laid computer programmers are using advanced technology to devise strategies for RPS success. RPS is often used to prove the game theory of nontransitivity, which rebukes the more logical theorem of transitivity, namely: if A beats B, and B beats C, then A also beats C. Notice the contrast with the rules of RPS: rock beats scissors, scissors beats paper, but then rock loses to paper.

This nontransitive neutrality can be compared to chess, in which both sides have the same number of identical pieces and the same number of potential moves. Because of the bluffing that can occur, some draw parallels between RPS and poker, and, not surprisingly, RPS has become a popular pastime on the World Series of Poker circuit. But there’s a major difference: in poker, you ultimately have to show your hand; in RPS, your bluff is your hand.

Looking at RPS from a mathematical perspective, playing the game in its purest form would mean making throws that were totally random. But alas, we humans are utterly incapable of random behavior. What we’re wearing, what we’ve had for breakfast, our mood, how much we can bench press… these all influence our choice of throws, and a keen opponent can pick up our tendencies rather easily.

In an effort to remove this psychological element, some computer geeks have developed programs that simulate random throws. But truly random play would make for a truly boring game: one third of the time you’ll win, one third you’ll lose, and one third you’ll tie…. In the long run, you’ll break even. That won’t get you very far in tournament play, as demonstrated in the 2003 International World RPS Championships, when a computer program called Deep Mauve was used to feed a player random throws—and was summarily ousted in the qualifying round.

Other, more advanced nerds have created algorithms that track past throws to detect patterns that may predict future throws. One program, Iocane Powder from Dan Egnor, devises throws based on the concept of Sicilian Reasoning, which uses six levels of metareasoning to make predictions. Subsequent programs have used this concept to create new strategies, such as Stratmove, which looks at the history of competing bots6 to find the longest same patterns played. Another, Bayesmove (named for mathematician Thomas Bayes), looks for any strange numbers to determine whether the competing bot is using random moves or employing specific strategies.

If both Iocane Powder and Sicilian Reasoning sound familiar, you’re probably a fan of the 1987 movie The Princess Bride. In the following scene, Cary Elwes (Westley) challenges Wallace Shawn (the Sicilian Vizzini) to a battle of wits to gain the freedom of Princess Buttercup. Two glasses are placed on the table, each containing wine and one containing poison:

WESTLEY: The battle of wits has begun. It ends when you decide and we both drink, and find out who is right and who is dead.

VIZZINI: But it’s so simple. All I have to do is divine from what I know of you. Are you the sort of man who would put the poison into his own goblet, or his enemy’s? Now, a clever man would put the poison into his own goblet, because he would know that only a great fool would reach for what he was given. I’m not a great fool, so I can clearly not choose the wine in front of you. But you must have known I was not a great fool; you would have counted on it, so I can clearly not choose the wine in front of me.

WESTLEY: You’ve made your decision, then?

VIZZINI: Not remotely. Because iocane comes from Australia, as everyone knows. And Australia is entirely peopled with criminals. And criminals are used to having people not trust them, as you are not trusted by me. So I can clearly not choose the wine in front of you.

WESTLEY: Truly, you have a dizzying intellect.

[After more back and forth, the two raise a cup to drink.]

VIZZINI: Let’s drink—me from my glass, and you from yours.

WESTLEY: You guessed wrong.

VIZZINI: [howling with laughter] You only think I guessed wrong—that’s what’s so funny! I switched glasses when your back was turned. You fool. You fell victim to one of the classic blunders. The most famous is “Never get involved in a land war in Asia.” But only slightly less well known is this: “Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line.”

[He laughs and laughs before falling over dead.]

BUTTERCUP: To think—all that time it was your cup that was poisoned.

WESTLEY: They were both poisoned. I spent the last few years building up an immunity to iocane powder.

It’s no surprise that RPS devotees pay homage to The Princess Bride, for this exchange perfectly captures the essence of Sicilian Reasoning—a deduction based on multiple levels of “if you know, that I know, that you know,” and a fundamental element of game strategy. An example: Even novice players know that rock is the most common opening throw. So if you’re playing someone beyond novice, chances are he will not throw rock… Or will he? Maybe he knows that you know he is not a beginner, and therefore he will throw rock because you least expect it.

The challenge is not to overestimate or underestimate the intellect of your opponent; essentially, one needs to know when to stop thinking and just throw. In 2005, a single-throw match was used between Sotheby’s and Christie’s to determine the rights to a pricey art collection; a Christie’s employee’s daughter employed flawless Sicilian Reasoning to offer this advice: “Everybody knows you always start with scissors. Rock is way too obvious, and scissors beats paper.” As reported in Fortune magazine and other major media outlets: Christie’s threw scissors and beat Sotheby’s paper.

*

Last spring, I attended my first competitive RPS event—the Chicago regional finals of the new Bud Light–sponsored USARPS League. Regional winners received a free trip to Vegas to compete for fifty thousand dollars and the chance to be crowned USARPS League champion. While all the other participants at Duffy’s bar qualified by winning tournaments at other bars, I somehow found my way into that night’s bracket. In the weeks prior, I built up my hand strength using a squishy stress-reliever ball and studied The Official Rock Paper Scissors Strategy Guide, written by the aforementioned Douglas and Graham Walker of the World RPS Society. Not surprisingly, the two sides don’t like each other much.

Since 2002, the Walkers have been hosting the Rock Paper Scissors International World Championships in Toronto; until the Vegas event came along, it was by far the biggest RPS event of the year in regards to cash prizes7 and media coverage. It certainly can be argued that the Walkers are responsible for planting the seed for this entire renaissance—these are the men who dusted off the long-forgotten World RPS Society (originally founded in London in 1842 as the Paper Scissors Stone Club) and brought it into the modern era with the launch of their website in 1995. And while the World Championships have grown from a wacky idea into a sizable and inspired geekfest—drawing contestants from all over the globe—the brothers were unsuccessful in one area: major corporate sponsorships.

Meanwhile, in 2005, USARPS League founders and co-commissioners Matti Leshem, forty-three, and Andrew Golder, forty-five, who produced a one-hour special on the 2004 World Championships for Fox Sports Net, sold the idea of a national RPS tournament to Anheuser-Busch. In a March 3, 2006, article in the Wall Street Journal, Golder says they were inspired to start the new league and apply more “show business” to the sport. The L.A.-based Leshem claims they tried to reach an agreement with the Walkers prior to the formation of the new league, to no avail. Graham Walker, a thirty-eight-year-old ad exec living in Prague, counters there was no real partnership offer, and even if there had been, he doubts the two parties would be able to resolve that age-old bugaboo “creative differences.”

According to the Walkers, the USARPS League is an insult, pointing to the website’s cheesy graphics and Playboy models posing as real RPS players. On Canada’s CBC television, Douglas Walker, thirty-four, a Toronto-based web consultant, said the USARPS League had the benefit of “standing on the shoulders of giants… and pissing downward.” During the buildup to the Vegas finals in April 2006, the World RPS Society site posted complaints of sloppy officiating at poorly run USARPS League events. It’s apparent the Walker brothers are concerned that either (a) Leshem, Golder, and Anheuser-Busch will run the sport into the ground, or (b) the USARPS League will be a success and overshadow nearly a decade of blood, sweat, and tears.

In the same Wall Street Journal article, Leshem, who clearly believes his league is the future of the sport, called the USARPS League “more rock and roll.” In a separate interview, he dismissed the World RPS Society’s highbrow claims: “No one owns RPS. RPS is a gift from God to the world…. We’re the purists because we’re a real league and they’re just a couple of guys with a funny idea.”

At the core of the rivalry is a fundamental difference in approach: while the Toronto World Championships were created as the ultimate road trip for fanatics and curiosity-seekers, the USARPS League was designed as a promotional vehicle to take RPS, and Bud Light, directly to the masses. And while there’s no denying Leshem’s love of the game—he often speaks of his childhood in Israel, when he and his brothers would play rock paper scissors to determine who would have to sleep next to the door during the bloody Six-Day War—according to the Walkers and their disciples, his hyped-up version is taking something eccentric and culty and forcing it into the frat-boy, spring-break-bacchanalia mainstream.

Back at Duffy’s, no one knows or cares about this rivalry—in fact, a few of the contestants are convinced I fabricated the whole story to gain insight into their strategy. While waiting for my first match, I order a Guinness at the bar, flip through my dog-eared copy of the RPS strategy guide, and memorize a few gambits, defined as “three pre-scripted throws made with strategic intention.”

Standing across from my first-ever competitive RPS opponent, I’m strangely nervous. My palms are dripping. The event is low-key—in fact, most bar patrons are more interested in the American Idol premiere on the TV than a RPS showdown—but along with thirty or so people in the corner of the bar, I’m sucked in to the pure energy of the moment. Ready, set, “Ro-sham-bo”—I begin with a gambit called “the crescendo,” a classy series that builds from paper to scissors to rock. My opponent, a cocky financial trader in his mid-twenties, is left reeling, so in the next set, after a few scissor ties, I finish him with the “denouement,” a mind-blowing cool-down of rock-scissors-paper (and the crescendo’s mirror image), earning myself a commemorative Bud Light RPS hand towel and a trip to the next round.

Round two, feeling confident and somewhat enlightened, I add a little glitz to my game. I perform elaborate arm stretches before the match. After we begin, I repeatedly call for time and slowly wipe my brow with my new commemorative hand towel. But soon I’m on the ropes. I never did catch her name, but I remember she wore

all black and didn’t blink once.

Her eyes locked on mine like a laser beam and I could feel her setting up camp inside my skull. Suddenly I’m making throws without any plan: no gambits, no instinct… rock, then paper, then rock again. I can still recall the steely aftertaste of her triumphant series: paper, followed by scissors, followed by another paper… The goddamn scissors sandwich.

*

At the Luxor, the poolside crowd is dominated by backward-baseball-hat-wearing twentysomething white males, all treated to a weekend’s worth of partying thanks to their friends at Anheuser-Busch. But a closer examination betrays a demographic divergence from this beer marketer’s wet dream: there’s a smattering of fiftyish guys in khakis on the periphery, looking slightly confused, like maybe they’re at the wrong trade show mixer. I chat with Mike, an insurance salesman from St. Louis. He says his wife still doesn’t believe he really won a trip to Vegas for playing RPS, even after he showed her the official winner’s voucher.

Plenty of young women are here too—some girlfriends, many champions in their own right. Also, it appears a few winners brought their parents. In less than thirty-six hours, this whole mass of humanity will reconvene at the House of Blues in the adjoining Mandalay Bay Hotel Casino, where they will glue giant plastic scissors to their heads, dress in ridiculous costumes to resemble Vikings or oversize ketchup and mustard bottles, and compete for fifty thousand dollars and RPS glory.

USARPS League co-commissioner Matti Leshem is a lanky and intense man. He sports a freshly shaven head and Hollywood facial fuzz and paces the party like a puma, giving direction to various film crews capturing the weekend for an A&E network special. I notice him pause for a moment during Too White Crew’s set to savor the pandemonium he’s created. Later that night, he introduces me to Jason Simmons, thirty-five, known in RPS circles as Master Roshambollah, the sport’s top ambassador. According to Simmons, he’s in Vegas to provide his “spiritual protection,” and his attendance at the tournament has angered many in the World RPS Society camp, with which he had a longtime alliance. Leading up to the USARPS League event, postings on the World RPS Society website referred to him as a turncoat and traitor.8

Bald and pensive, Simmons looks and feels like RPS’s version of David Carradine from Kung Fu. He created the Master Roshambollah character in 2001 while working at consulting giant Arthur Andersen; when the company was going down the shitter, he stumbled across the World RPS Society site, thought it was funny, and started posting messages under the guise of this “spiritual con man… part Baptist minister, part used-car salesman.” Soon, he hosted his own tournament at the Burning Man festival, and, as the Toronto World RPS tournaments started to attract media attention, Master Rosh, as he’s often called, was featured prominently. While he positions himself as the number one player in the world, he has never won the World Championships in Toronto (he finished fifth in 2003). But in RPS, sometimes simply saying you’re a champion, and acting like a champion, are enough to make it so.

But there’s no denying Master Rosh’s magnetism, and Leshem was wise to enlist his help. And you can’t blame Simmons for wanting to perform on a larger stage. In a 2004 Washington Post article about a local tournament, Simmons said his ultimate goal was to serve as a commentator for the sport. It sounded ridiculous at the time, but here in Vegas he was providing just that service for A&E.

Leshem suggested I play Master Roshambollah in a match, which proved humiliating. After a few stalemates, he beat me without breaking a sweat. It happened so fast I can’t recall any of my throws. Was I offering tells? He didn’t elaborate, except to say that he picked up on a pretty common algorithm. There was something in his calm confidence that made me believe him, and I did notice a momentum change, a point where I was suddenly put on the defensive. Master Rosh chuckled politely, and likened it to the hunt, where the hunter doesn’t let the hunted know he is being hunted until… or something like that. He then showed me how a slight twitch of the finger (call it a muscle spasm) can throw off a hand-watching opponent: “With a receptive opponent, if they see the scissors, chances are they’ll throw scissors,” he said. Master Rosh refers to this as an ancient Hindu technique called “subliminal advertising.”

After my time with the master, I make my way into the crowd and test my skills on a spunky young blond from Toledo, Illinois, named Ashley. She lifts her shirt to expose a long scar on her midsection and explains she could really use the fifty thousand dollars to pay her medical debts. Locked in, and not nearly as drunk as Ashley, I dominate our match. I was done with gambits—this was all instinct. I lean heavily on scissors, forcing stalemate after stalemate, and then drop in a rock to close the show. Wandering the casino over the weekend, I meet more contestants and consistently beat them by just opening my mind and feeling what I should throw next. Was I finding my way on what Master Rosh called “the path”?

*

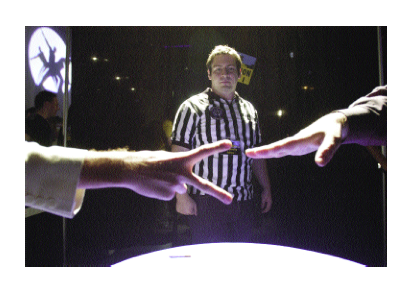

Contrary to reports from the regional tournament rounds, the officiating in Vegas is crisp, overseen by legendary boxing referee Richard Steele. But now the pool is down to the final two. Gone is Amber, the former child runaway whose pen-scrawled message “scissors first” across her bare midriff foiled many an adversary. Gone is Dave, the young hippie from Boulder who favored rock and carried a notepad to tally the throws of his next-round opponent. Even the costume contest winners are done, a father and son dressed as Barney Fife and Otis the Town Drunk from the old Andy Griffith Show. (Fan favorite Otis made it all the way to the Sweet Sixteen, but now he’s crumpled into a heartbreaking ball of seersucker.) All of them, once untouchable, are reduced to bystanders. Some pick at the remnants of the complimentary buffet; most continue to hoard Bud Light as this magical weekend of free beer and RPS-inspired craziness nears last call.

The ladies of RPS, including former Playmate of the Year Brande “Rock” Roderick, saunter provocatively along the stage to let everyone get one last look at them before the climactic match gets under way. The host, comedian Dave Attell, makes a few wisecracks to lighten the mood. He refers to RPS as the second-best drinking sport, behind cockfighting. Most of the audience is exhausted, and there’s an almost eerie silence in the room. Is it anticipation? Or does everyone just want to go home and take a nap?

And now, here we go, Robert “Fast-Twitch” Twitchell head-to-head versus Dave “The Drill” McGill. The winner goes home fifty grand richer; the loser is cursed to spend the rest of his days second-guessing his strategy, knowing he’d come oh-so-close to immortality.

On the surface, both these Midwestern white guys look like prototypical rock tossers. St. Louis–bred Twitchell works in construction and is built like a beanpole, his blond crew cut and fidgety attitude calling to mind a young Vanilla Ice. He stood out among the field for his textbook form, and for a propensity for throwing scissors when backed into a corner. McGill is a compact, wholesome-looking thirty-year-old college sophomore from Omaha who likes to lift weights. He leaned on rock in earlier rounds, but his sly smile betrays a devious nature: like Twitchell, he won his previous match wielding scissors.

I found it interesting that among all the over-the-top costumed characters and pseudosavant Mensa members, these two regular Joes were the last ones standing. Talking with both, I didn’t get the impression they’d thought much about RPS until that fateful night a few months prior when a cute Bud Light girl tapped each on the shoulder at their respective local watering holes and asked: “Hey, you wanna play rock paper scissors?” These guys weren’t intimidating. Hell, after having spent some time with Master Rosh I felt like, on a good day, I could take either one.

Unlike the computer nerds who try to program victory or the satiric Zen Buddhists who’re making careers out of RPS, they were both real-life Cinderella stories, and watching them eyeball each other here in a mini boxing ring—both thinking they knew something the other didn’t, each feeling there was a legitimate reason that they had just won seven matches in a row—made me believe more than ever that, yes, RPS is a sport, and a glorious one at that. Whether the game is poker or water polo, winning breeds confidence. And these two warriors had it in spades.

It wasn’t bullshit when Graham Walker told me that the best thing about RPS is that anyone can compete at the game’s highest level: “You have to train all your life to be in the Olympics,” he said. “But with rock paper scissors, as long as you have one functioning hand—actually, even if you didn’t have any hands, we’d make some allowance.” Indeed, despite their differences, this democratic approach is one area where the World RPS Society and the USARPS League are undeniably on the same page. Both believe RPS is a game of the people, a game where anyone can get in the zone, find enlightenment, and walk away a champion.

The real fun of competitive RPS—and the reason fifty-year-old insurance salesmen are having the time of their lives here in Vegas alongside twenty-two-year-old frat boys—is the fact that once you spend a bit of time in this world, once you take a sip of the Kool-Aid, you can’t help taking it all very seriously… even if that seriousness is expressed in a very tongue-in-cheek way. Like any sport, there are rules you must follow and various strategies that may or may not lead to success. But unlike so-called “real sports” like boxing or baseball, there’s a magical innocence to RPS. Or at least there should be.

Yes, there’s bravado and shit-talking, but everyone who agrees to take part shares a strange reverence for this game most of us first played as children or in college. Competitive RPS brings us back to those carefree days; we feel nostalgia and amusement when we compete against other adults for big money on a very big stage, or for free beers in the back of a corner bar, but we also feel a sense of pride. The game has moved beyond the schoolyard and dorm room. Like us, RPS is all grown up.

And while some may argue that the forced fun of this Spring Break in Vegas atmosphere lacks the purity of the groundbreaking International World Championships in Toronto, the flashiness provided by Leshem and Big Beer has taken RPS beyond an inside joke and introduced this competitive version of the game to thousands of new fans. For better or worse, pumping RPS full of steroids has legitimized it as a sport in the modern era. With slam-dunking mascots and anthropomorphic sausages running the bases between innings, sporting events in America have become ridiculous spectacles. And was there ever a game so perfectly suited to ridiculous spectacle as RPS?

The Walker brothers of the World RPS Society were the pioneers and should be revered accordingly, but the increased competition supplied by the USARPS League, which also plans on holding its tournament annually (the 2007 championship is scheduled for May 2007), will challenge all of these very creative people to up the ante even further… to make each event bigger and better than the last. If the Walkers are the “inventors” of modern RPS, the Abner Doubledays, as it were, then maybe history will view Leshem as the Bill Veeck, that shameless baseball promoter who built the exploding scoreboard and once sent a midget to the plate. There’s an American League and a National League in baseball… why can’t there be two leagues for RPS?

Finally, the moment everyone’s been waiting for. It’s go time.

Ready, set, “engage”—McGill’s in charge early with a first-set victory, but Twitchell digs deep and takes the second set with a commanding rock. We’re all tied up. Interestingly, Twitchell avoided rock the entire previous round, but either due to fatigue or a mental shift back to his true tendency, he favored it when the match was on the line. But in a brilliant move, McGill goes against type in the defining third set and wins the tournament and fifty thousand dollars with the ultimate in passive-aggressive play: with a gambit known as “the bureaucrat” (paper-paper-paper), McGill’s final throw of paper beats Twitchell’s rock to take the crown.

Immediately following his victory, McGill is already acting the part of reluctant hero. There’s something a little vacant in this, the pinnacle moment of RPS history. When asked what it feels like to represent the sport of RPS, he scoffs, referring to himself as a natural, a savant, the best, anything but a role model. The film crew is having a hard time securing a postvictory sound bite that doesn’t include the word fuck. During this acknowledged apex of his existence, McGill is already bitter, barking about his distrust of the media and how God liked him better than the other guy. Maybe he’s joking around. Or maybe it’s because he has been drinking for five hours straight. But he has just won a rather significant amount of money for playing rock paper scissors, and he should be happier.

The rise of RPS as a big-time sport and the camera glare of ESPN and countless other media had created an unwelcome by-product: the gifted athlete who doesn’t appreciate the game that made him a star. I guess that’s the chance a league takes when it plucks tournament participants from among the masses and transforms an everyman into a luminary. RPS lost its innocence on this day, joining the ranks of other once-proud pastimes. Here was the irrefutable evidence that RPS was indeed a real sport: Unfortunately, RPS now has its own mirthless Barry Bonds, its own ungrateful and belligerent superstar. Like most sports heroes, Dave McGill was already acting like an asshole.