Scouts and Indians and Frustrated Austrian Painters

My father says there were nine of them, mostly boys. Some carried bows and arrows whittled from willow twigs. Others brandished sticks trussed with broken cobblestones. Feathers poked from blond skulls. It was a weekday in a small German city in early 1945, and school was officially disbanded for weeks, maybe years.

The Indians whooped and danced around a lone captive tied to a lamppost. He was the scout, a surveyor who’d come to the American Wild West to make his fortune and fallen into the hands of people with fantastic leather outfits and feathered weaponry. He strained at the knots. He needed to break free and fight them and win.

All of a sudden, above their howls, the children heard an unmistakable shrieking. Tomahawks faltered as they looked up to see a low-flying British fighter plane streaking over their heads.

The Indians had a split second to choose. Some glanced at the boy at the stake before sprinting away. Others simply ran. Weapons clattered to the ground as they hurried into the closest house and jostled up the stairs. They huddled together behind a window, waiting for the plane to fly back and fire its bullets. No one looked at the boy now. They had left him behind.

The plane roared past and swung away. The boy blinked in its wake, alive. The city would be smashed by bombs three weeks later, then surrendered, then occupied. Yet the children’s imaginary America did not change even after real U.S. soldiers filled their streets, posing in photographs and doling out chocolate bars. That faraway country—of beautiful mesas, brave escapes, and colorful tribes—would always belong solely to the German people, and to an author of adventure stories named Karl May.

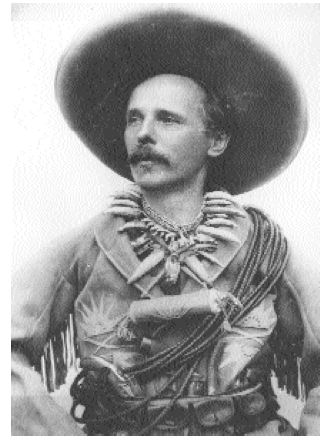

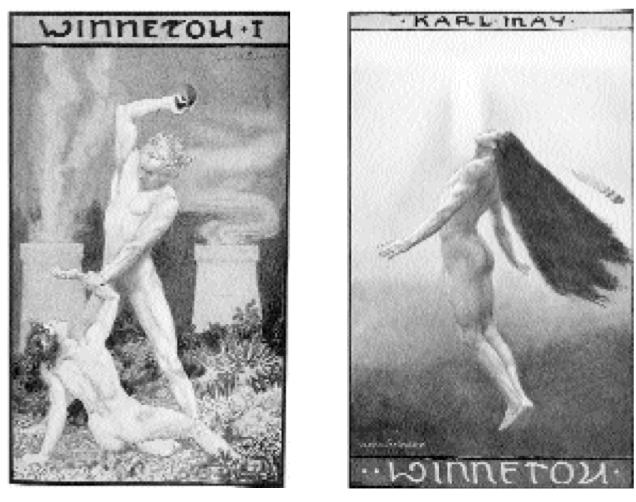

Although Karl May (pronounced “My”) remains, ironically, unknown in America, he was—and still is—one of the world’s most popular adventure writers, penning more than sixty books between 1875 and 1910. From Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany all the way through the Third Reich and beyond, May captivated adults and children alike with the exploits of Old Shatterhand, a German scout who’d traveled to the West as a surveyor, and Winnetou, the velvet-eyed Apache prince who becomes his blood brother.

May’s stories have been translated into two dozen languages and have sold more than 100 million copies. His books feature back-cover blurbs from Albert Schweitzer, Herman Hesse, and even Albert Einstein, who claims, simply, “My whole adolescence stood under his sign.” Over thousands of best-selling pages, Old Shatterhand and Winnetou gallop about on Mustangs and gun down grizzlies, spy from secret hiding places and try to stop...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in