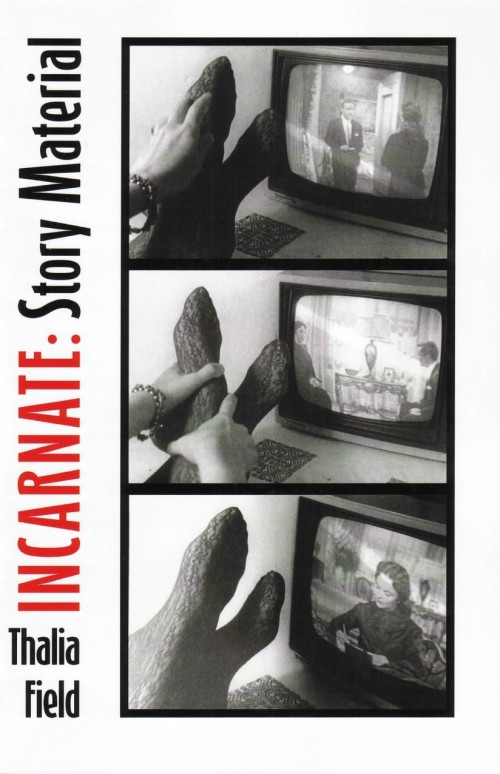

Thalia Field’s Incarnate: Story Material is comprised of fourteen texts differing markedly in voice, style and genre, yet it coheres internally through thematic recursions and aesthetic inventiveness throughout. In the poem “Autocartography,” Field has searched her proper name on the web and “found herself” elsewhere, discovering alter-egos in all manner of “thalia fields and related sites.” Woven throughout the poem is the story of Comanche captive Cynthia Anne Parker, as well as percussive directives—Make a Rain of This, Make a Dwelling, Make a Hunt, Make a Video Game—which read as both playful invitations and pedagogical assignments. (Field is a professor and a practitioner of page performance. Among other things she teaches a class on page-as-proscenium called “Performance Dimensions of Text” at Brown University.) In “Flickering,” a swarm of parentheses surface like newts or water insects encircling and splitting off from each other. The haunting title poem “Incarnate,” defines hell as prison. The numerology of suffering and abjection is figured: 44,435,556 are the number of demons in hell—more than the number of humans incarcerated on earth: approximately eight million.

“Story Material,” the subtitle piece, is printed vertically (as was “Seven Veils” in Field’s first book, Point and Line). “Story Material” performs an energetic cut-up of The Odyssey. Epic melodrama and lyric beauty is renewed, but lyrically reconfigured by Field-as-interlocutor. “Pine,” which deals with an ugly land dispute, is parsed into a series of wry reflections:“hopes up / hopes was up / what you read / when it becomes / clear you are / reading into it.”

The final text, the clear-sighted and, to my mind, effectively activist play “Zoologic,” is an exemplar of Field’s powers and preoccupations. Anxieties about overdetermined terrains—“You can’t write because it’s already written” and “I went to become an individual but everyone had already become it”—are related to loss of habitat, read against the ecological catastrophe of human-centrism, as exemplified by zoos, displays of “only a few live examples.”

In this tour de force, Thalia Field’s aesthetics and ethics converge in a passionate chorus:

that individuals live mosaically

that free-living animals don’t stand in silhouette

against man-shaped backgrounds

that prison cells do not overlap (the fighting!)

that at the end of individuals: (individuals!)

that we think thinking stays congruent with thinking

each species to its world a mere technical mimicry

ours for minds under overarching regimes

ours for the identity of numbers.

...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in