Over and over, in Tayari Jones’s darkly comic and vividly heartbreaking novel The Untelling, the main character’s mother asks with inherent disapproval, “Is this what Dr. King died for?”

Atlanta is the novel’s setting, and the memories of Dr. Martin Luther King are everywhere—as street signs, as physical markers, and as a heavy presence of expectation for Aria, the narrator, whose real name is Ariadne, and whose mother has very specific designs for all three of her girls. “Her gifts to the three of us were lush, extravagant, roomy names. Names that fit us like oversized coats, trimmed in seed pearls, gold braid, and the hides of baby seals. My father had wanted us to have family names, with at least one of us girls named after his mother, Lula. My mother, who indulged my father in many things, could not give him this. Why, she wondered, would someone in this day and age give a child a name that was so Mississippi? ‘That is not what Dr. King died for.’”

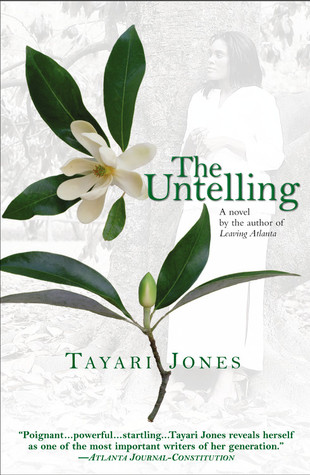

Ariadne’s life, and her family’s very existence, is fragmented like a broken windshield when her father’s burgundy Buick crashes into a hundred-year-old magnolia tree. Ariadne’s mother, clutching baby sister Genevieve in the front seat, thinks she has saved her. But she hasn’t. Older sister Hermione climbs unharmed from the wreck, while her father, trapped behind the steering wheel, bleeding internally, asks nine-year-old Ariadne to stay with him. But Ariadne, in her childhood coldness and fear, cannot. “My sweet Daddy who gave me two-dollar bills for every A on my report card. To the only man who had ever loved me I said, ‘I’m not listening. I can’t hear you.’”

Left to their own descent into lower middle-class existence, Aria, her sister Hermione, and their mother live with hate and guilt carried like grocery bags soldered onto their forearms. Her mother works at the Institute for The Blind. Hermione marries her father’s best friend and leaves the house at seventeen. And Aria attends Spelman, but doesn’t meet a Morehouse man like her father.

By her adulthood, the only other man to have loved her is Dwayne, a locksmith, and though they are not truly in love, not yet, Aria believes she is pregnant, and Dwayne asks her to marry him in response and obligation which turns to actual love. But Aria, having been raised with her mother’s anger and regret and borderline insanity, believes she isn’t worthy of love. During her brief stint working for her mother, she meets an angry blind client. He says,“I don’t mean you no harm. It’s hard not being able to see things. Waiting for somebody to tell you what’s in front of your face.” When he tries to assault Aria, her mother asks him to leave, and turns to Aria: “It’s you. Only you could almost be raped by a blind man in a public place. Is this what Dr. King died for?” To Aria’s mother, Dr. King died so that her daughters could live the lives she expects for them: educated, equal, upper middle class, and perfect. But neither of her daughters fulfills her “I have a dream” expectations.

Atlanta is a fully-realized and vibrant character in the novel. The road where Aria’s father died has been renamed for Martin Luther King, and the fork in that road for Ralph David Abernathy. Tayari Jones is so talented with metaphor and with dialogue that each house and neighborhood and room came alive for me: the seedy West End where Aria lives with her college friend Rochelle, the house turned into a literacy center where Aria and Rochelle work. Aria tutors a roomful of girls: “All of them seemed to be wearing silver bracelets or multiple pairs of gold earrings. Their acrylic nails ticked together as they guided their pens across lined paper. The din was like every religious noise I have ever experienced or heard of. Like rosary beads clicking, the clanging of finger cymbals.”

The first person Aria tells about her condition is Keisha, a pregnant teen trying to pass her GED test: “The words slipped from between my teeth easily, like oiled melon seeds. It was a dumb thing to do. I knew this before I finished my sentence, just like you know when you’ve locked your keys in the car even before the door slams, but there is nothing you can do but watch.” As the novel moves forward, and Aria tells Dwayne the truth of what doctors discover about her, and as Aria discovers truths about her own mother and sister, Jones never falters with her impressive combinations of lush description and deadpan humor: “The crackhead neighbor Cynthia, who has had three children and raised none, looks for a lost rock of cocaine in Aria’s driveway and says sardonically, ‘Keep hope alive.’”

Tayari Jones writes of Fashion Fair lipstick as a relic of a particular time, of the hard-edged optimism of black women like her mother, and of the contradictions of now, perfectly expressed by Dwayne when he disapproves of Aria’s neighborhood: “It’s the worst of both worlds. You live in the ghetto with a bunch of bourgie Negroes.” What happens to Aria, when the truth is told and the lies are untold, when her mother confesses and her sister holds her, is never sentimental or false, to Jones’s credit. What Aria reaffirms for herself at the end of this amazing novel, is this:“The past is a dark vast lake and we just tread on its delicate skin.”