In 1998, Sonallah Ibrahim reportedly feigned illness to avoid receiving Egypt’s best-novel prize. In 2000, he quietly turned down the American University in Cairo’s Naguib Mahfouz Medal. But in 2003, when offered the Egyptian government’s prestigious Novelist of the Year award, Ibrahim could no longer keep his silence. The sixty-six-year-old author took the stage and ended his brief speech by saying he would not accept a literary prize from “a government that, in my opinion, does not possess the credibility to grant it.” He left the prize and walked out.

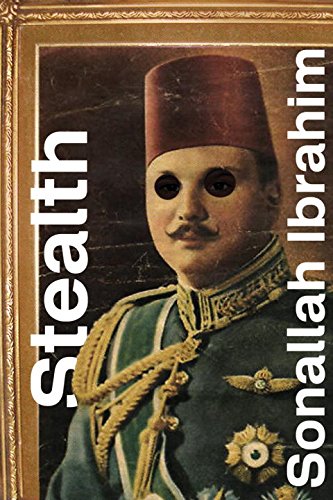

Sonallah Ibrahim has spent a lifetime clipping newspaper articles, quietly defying regimes, and writing clear, unsentimental fiction that is at times absurdist and at times difficult to distinguish from daily Cairo realities. His latest novel, Al Talassus—which could be Eavesdropping or Sneaking, but is translated by Hosam Aboul-Ela as Stealth—is perhaps Ibrahim’s least overtly political work.

Stealth follows a young boy through Cairo in 1948, during the turbulent period between World War II and independence. As with many of Ibrahim’s other novels, the line between fiction and reality is difficult to locate. Many have surmised that this is the story of Ibrahim’s own childhood. He is, after all, the son of a much-older father; he had an impoverished upbringing and wealthy half siblings; his young mother was absent. But Stealth is not a memoir. One of the book’s most gripping moments is when the narrator holds stock-still, watching a bedbug but unable to kill it because, were he to move, his father would notice his wakefulness and stop telling his deepest secrets to a friend. Ibrahim’s sister apparently called him after the novel was first released to argue that their father did not have bedbugs.

The narrator, whom Ibrahim says is “between six and eight years old,” is curious but not precocious. He doesn’t know what questions he should ask to turn up the information he needs. He has the occasional astute query, such as “How old is mother?” which he asks after overhearing someone mock men who take young brides. (Twenty-six, we discover. His father is in his middle sixties.) But even if the narrator can’t shape his questions into language, we sense them along with him. What has happened to his mother? Will she come back? Will his father marry again? Why are they so poor when his adult half sister, Nabila, has everything she wants?

The novel’s...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in