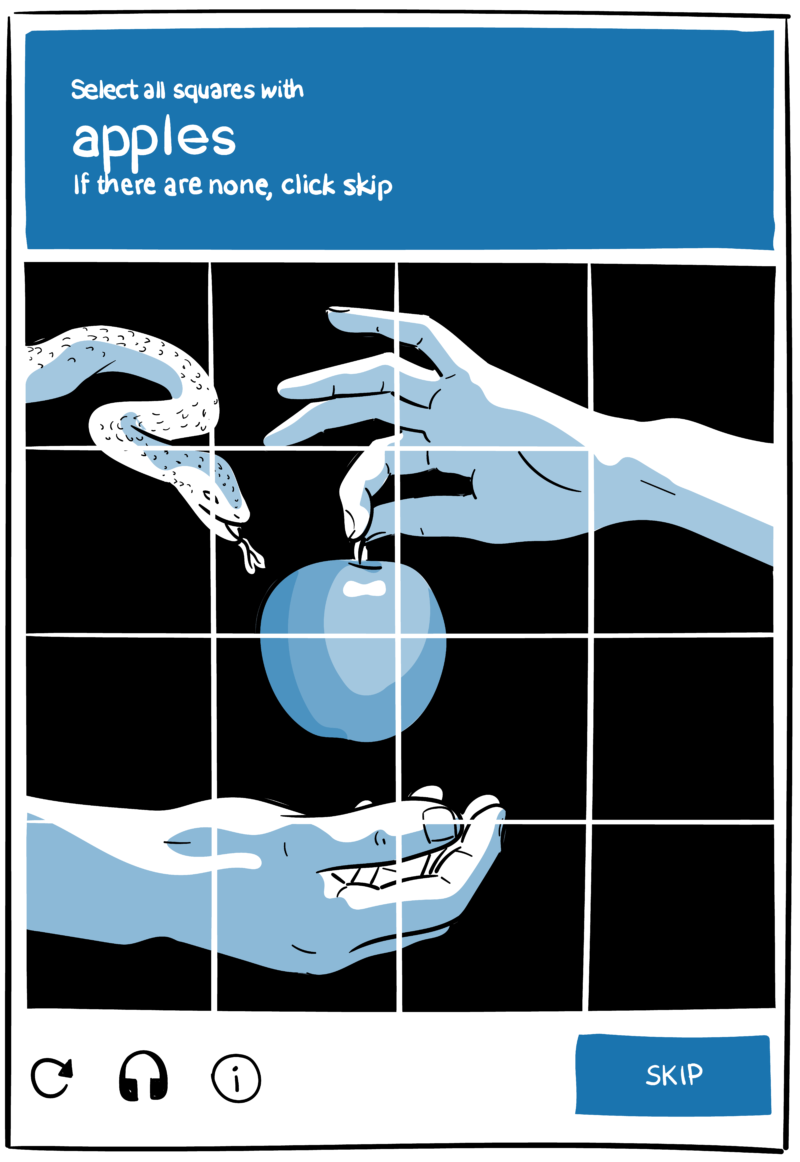

The exhibition began, like the fall of mankind did, with an apple. Or rather, it began with a glut of photographs of apples: red apples, green apples, yellow apples, sliced apples, bushels of apples, an apple with the word “Google” carved into it. These images were pinned to a wall and clustered around a label featuring a single, simple noun: “apple.”

This was From ‘Apple’ to ‘Anomaly,’ on display at the Barbican Centre in London in 2020. For the project, the American artist Trevor Paglen culled around thirty thousand images from the online database ImageNet, printed out small-scale versions, and pinned them to a lengthy curved wall, categorized by noun: “soil,” “valley,” “syringe,” “pizza,” “mascot.” The result was breathtakingly expansive: seen from a distance of a few feet, it resembled a shimmering mirage of animals, plants, minerals, and people.

The near-infinite visual library was possible because ImageNet is one of the largest publicly available libraries of images. It is also the pioneering dataset for much of the world’s image-recognition technology. Everything from Facebook’s self-tagging feature to self-driving cars to drones is trained to see the world using massive datasets like ImageNet. It was amassed over the course of nearly a decade, largely by workers who, for pennies, matched images to associated words on the task website Amazon Mechanical Turk. The result was a dataset of more than fourteen million images, cataloged and labeled so machines could learn to match an image of a rose to the word “rose.” Paglen made visible this wild, freewheeling taxonomy of everything under the sun, including the sun itself.

In 1668, an English clergyman and natural philosopher named John Wilkins unveiled a similarly vast project: he renamed the world. In his masterwork, “An Essay towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language,” which ran to almost seven hundred pages, Wilkins laid out a template for a universal language, one that would be so perfect in its powers of expression that it would bring humans closer to God and “not signifie words, but things and notions.”

Wilkins was writing against the backdrop of the English Civil War and the loss of Latin as a common Christian language. He was also grappling with an enduring human problem—the gap between words and their meanings. In an essay about Wilkins...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in