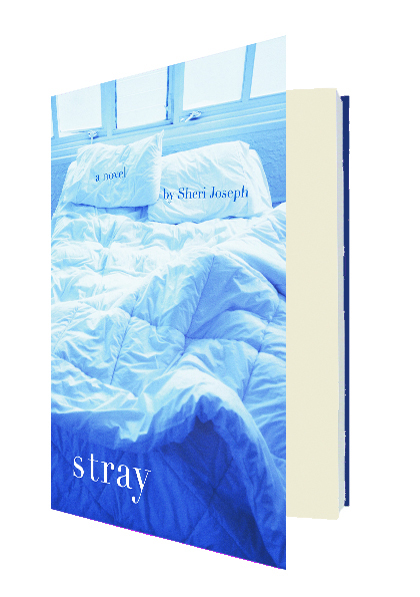

The cover of Sheri Joseph’s first novel, Stray, features a bed in disarray, still bearing the imprint of absent bodies, the white comforter awash in blue light. The image suggests something delicious and probably untoward; there is the hint of a hasty retreat.

No surprise, then, that the novel opens with a post-coital conversation between two men at a borrowed condo in Florida in which twenty-one-year-old Paul raises the specter of his lover Kent’s marriage, accusingly, “as if the marriage and not his presence in this bed were the character flaw that Kent should examine.” Paul goes on to pose an impossible question: “When you’re with her, do you think about me?” Kent, a thirty-three-year-old musician who is dangerously far gone in his love for Paul, commits the sin that will ultimately bring the two halves of his life together: “with a word, he opened the first door on his marriage.”

Paul and Kent made their first appearance in Joseph’s critically acclaimed story cycle, Bear Me Safely Over, which ends four years prior to the beginning of Stray. Now Kent is happily married to Maggie, a Mennonite who is devoted to her work as a public defender and who knows very little about her husband’s previous life. Kent has relegated Paul to an uneasy part of his memory, where he might have safely remained had the two not bumped into each other one Sunday night at a university library. The trip to Florida is Kent’s attempt to end the relationship for good, but first loves have a habit of hanging on inconveniently, and this one is no exception.

The third-person narrative shifts chapter by chapter among four characters: Maggie, Paul, Kent, and Bernard, the ailing professor of drama with whom Paul lives and who cast Paul in his first significant role—Hamlet. Fittingly, Bernard played the ghost of Hamlet’s father. The shifting third person allows us to see Paul’s intimate and often destructive influence on the lives of those he loves. In a teeth-gritting plot twist, Paul secretly meets and befriends Maggie, whose affection for the young, aspiring actor is maternal but not entirely asexual, and whose conversations with him reveal Paul’s vulnerability, which Kent is largely unable to see.

In fiction as in life, a love triangle can be a mightily dangerous thing, and a reader might be tempted to turn pages faster than one usually does in a literary novel, anticipating the inevitable train wreck. If the plot makes you want to speed through the book, the descriptions will make you want to slow down. Atlanta, the author’s adopted hometown, is rendered in sharp observations. Kent and Maggie’s street is “narrow, lined with close-set, one-story wooden houses that had been shabby ten years ago but were now loved again… With its rocking-chair porches and arty wind chimes and flags, the neighborhood exuded an air of determined cheer, a hint of self-congratulation.”

Determined cheer, or cheer of any kind, for that matter, is absent from the novel’s closing scenes, which provide no quick solutions for the complex questions of intimacy, infidelity, and sexual identity that are raised in the opening pages. No characters end up happier than they were at the beginning of the book. One even ends up dead. Which is to say that Joseph offers a realistic, if grim, perspective on the risks we take when we succumb to that most human weakness—desire.