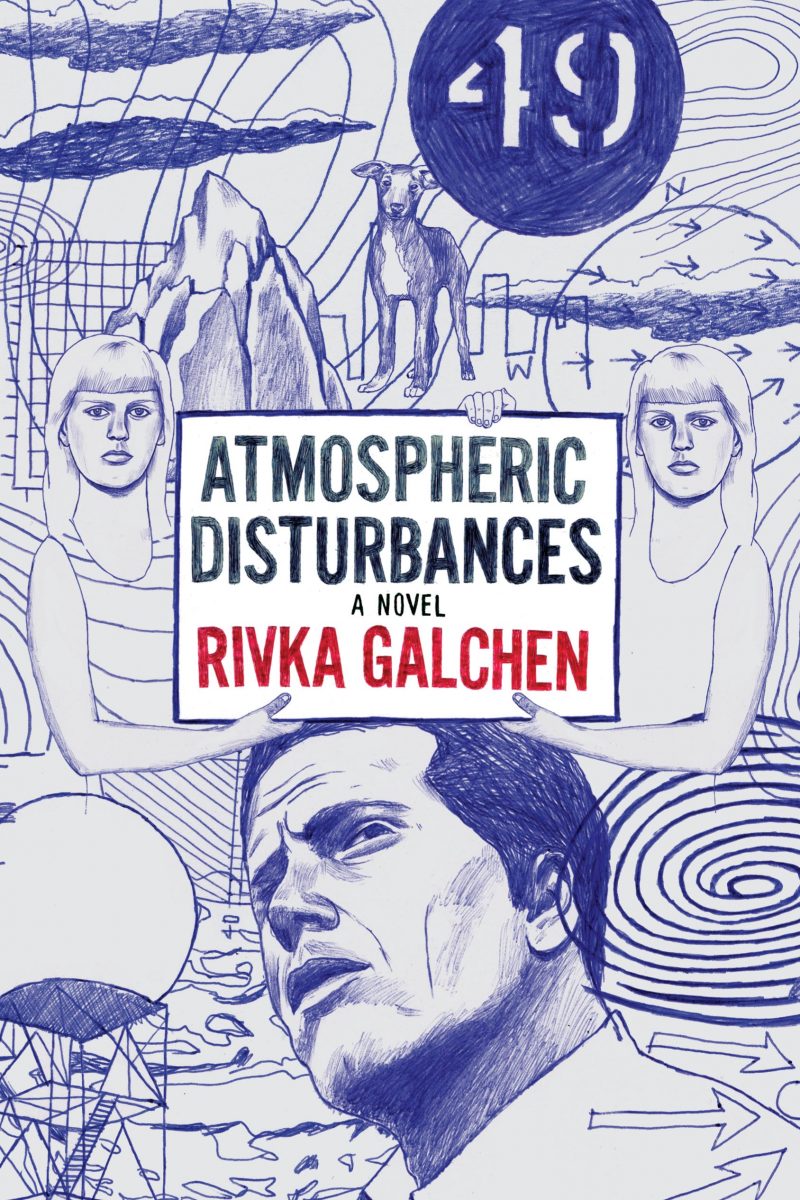

Rivka Galchen’s riveting debut, Atmospheric Disturbances, toys with many of the traditional mystery-novel tropes and makes us question, yet again, what distinctions exist, if any, between so-called “literary” and “genre” fiction. Between art and not art. But this is no ordinary whodunit: there’s a whole lot more at work here, intellectually speaking, than you’ll find in those airport potboilers. Maybe it’s a kind of anti-mystery. As in some of Paul Auster’s most mind bending, early fiction, Atmospheric Disturbances brilliantly raises more questions than it answers. If anything, we know even less when it’s all over than we did when we started. But Galchen is no Paul Auster nor is she meant to be—she might be even better.

Our hero is Leo Liebenstein, a fifty-one-year-old New York psychiatrist “with no previous hospitalizations, and no relevant past medical, social, or family history” and an excessive fondness for cookies. His Argentine wife, Rema, has disappeared and been replaced by a nearly identical “impostress” or “simulacrum.” Only he can tell them apart, and the novel follows his tilting-at-windmills efforts to find the “real” Rema. He turns for help to one of his patients, an absinthe junkie named Harvey who believes himself to possess “special skills for controlling weather phenomena” and to work for a secret society known as the Royal Academy of Meteorology. Liebenstein does little to disavow him of these notions. The science of meteorology looms large in the novel, both literally and metaphorically. The noted meteorologist Dr. Gal-Chen—a relation of the author’s own fictional Doppelgänger?—could very well be involved in whatever has happened to Rema. He may also be dead, but that doesn’t prevent him from occasionally answering his email. As Liebenstein digs deeper into the apparent plot, it turns out that he may have bigger problems to deal with than a missing wife. His sleuthing takes him to Buenos Aires, where he rents a room from Rema’s estranged mother, Magda. His “fake” wife soon follows him, and she’s so convincing in her verisimilitude that, to Liebenstein’s consternation, Magda doesn’t even realize there’s been a switcheroo:

“I had miscalculated the internal error of the other observer I was observing; I should have know that a mother who has not seen her daughter for years, who so desperately wants to see her, well, one could put Kim Novak in front of her and she would likely ‘recognize’ her as her daughter,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in