When you meet a Galápagos tortoise, as I did recently, it will do one of three things. If annoyed, it will turn and lumber off across the volcanic tuff. If afraid, it will thud onto the lava and pull in its head, like a toddler who thinks she becomes invisible when she covers her eyes. Or, if it is feeling comfortable, it will fix you with Triassic eyes. It can do this for ten minutes without getting bored. Possibly longer. I challenged several to a staring contest, but I always blinked first.

To meet the gaze of a Galápagos tortoise is thrilling and slightly unnerving. True, it has the vacuousness appropriate to an animal with a brain the size of a walnut. And yet in its eye is a quality absent from, say, the stare of its neighbor and distant relation, the marine iguana. The tortoise has a sentience, an alertness and seeming comprehension that marks the line between ignorance and indifference. It’s not that the tortoise doesn’t get it, one feels; it’s that he just doesn’t care.

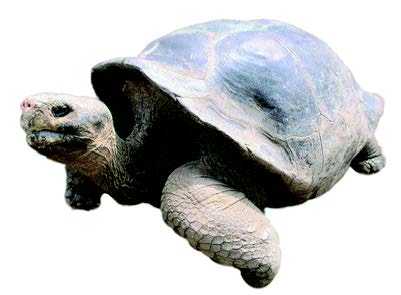

This attitude is understandable. The giant tortoise can weigh up to 600 lbs. Its carapace, or topshell, can be 4.5 feet across and is thick and heavy. Its scaly skin protects its limbs like a motorcycle jacket. Its ancestors have trod the rugged, lunar landscape of the Galápagos since before chimpanzees split off from protohumans. For three million years, giant tortoises have stumped, peglegged, across the lava, eating whatever plants happened to have evolved recently. Charles Darwin once clocked one at two tenths of a mile per hour. It is believed to be the longest-lived animal on earth, yet no one knows its lifespan. It may live 200 years.

Tortoises float. They have a built-in life jacket made of fat on their backs, under the carapace. Once in a while, a tortoise stumbles off a cliff, is driven offshore by the weather, or simply gets confused, and ends up in the ocean. It can survive for a year or more without water, so its only maritime concern is breathing. The tortoise’s patience is a real virtue at sea. The first colonists tumbled in from the coast of South America, riding the currents some 600 miles west to the Galápagos, which sits sidesaddle on the equator. My Galápagos guide told me that fishermen have reported seeing tortoises floating peacefully in the open ocean.

Thus, tortoises have colonized all the major islands of the Galápagos. Biologists now recognize eleven different kinds of Galápagos tortoise. Some of the farthest-flung varieties are the most closely related. The shells vary from island to island. On moist islands, they tend toward a domeshape. On more arid islands, with less succulent vegetation, one finds the so-called “saddleback” form. The saddleback shell comes to a high ridge just behind the tortoise’s head. Saddleback tortoises also have a long neck and legs, adaptations that give them a greater reach. Tortoises eat leaves, grass, and cactus pads. Their softball-size droppings often contain still-sharp spines. On islands with saddleback tortoises, the cacti try to lift their juicy pads out of tortoise reach, with a treelike trunk covered with scaly bark. It is an evolutionary race at a tortoise’s pace. The front of the saddleback carapace looks just like an old Spanish riding-saddle called a galápago. In the sixteenth century, the Spanish Bishop of Panama thought so, too. Becalmed, drifting tortoiselike, his ship bumped into the islands. He found little or no water there, but muchos galápagos. The name stuck.

For 2.9995 million years, the adult tortoise had no enemies. (Tortoise eggs and babies fell prey to birds. After that, for millennia, they were home free.) Recently, though, its remarkable adaptations have turned into liabilities. For the last 500 years, its principal enemies have been pirates, adventurers, and scientists.Tortoise back-fat can be rendered into a clear, cleanburning oil. Tortoise meat meant the difference between life and death for many sailors and colonists. Sailors discovered the tortoise’s ability to survive without food or water. They stacked the silently suffering animals upside-down in the hold of a ship for fresh meat at sea. A large ship might have taken 200 or more. It is estimated that 700,000 tortoises were killed by buccaneers, whalers, and other seafarers before the animals were protected. About 2 percent of that number survive today.

Charles Darwin, the father of evolution, ate his way through many varieties of Galápagos tortoise. During his visit to the Galápagos in 1835, as part of the voyage of the Beagle, he lived on tortoise meat for weeks on end, collected a few for scientific purposes, and filled his ship’s hold with live tortoises, over easy. Darwin was not yet an evolutionist, and the tortoises did not make him one. He realized their evolutionary importance only later, back in England. In the Galápagos, they mainly supplied food and entertainment. Darwin thought the (dome-shaped) tortoises of James Island, also called Santiago, tasted best. As the crew ate their catch, they threw the carapaces overboard. Darwin tried to ride tortoises, making them giddyap by rapping on the back of the shell, but the stiff-backed Victorian kept falling off. At some point last century, someone exported two Galápagos tortoises to the Knowland Park Zoo, in Oakland, California, where, as a child, I delighted in riding them around their little pen. It wasn’t that hard.

You can no longer remove tortoises (or anything else) from the Galápagos. In 1959, the centennial of Darwin’s Origin of Species, Ecuador established the Galápagos National Park. Five years later, the Charles Darwin Research Center was founded. These two institutions work together, mostly, to preserve the delicate ecology of the Galápagos. In 1965, the Darwin Center began a tortoise captive-breeding and repatriation program. Females lay from seven to twenty eggs—many fewer than most turtles—then walk away. Biologists dig up the eggs and bring them back to the Darwin Center. Eggs incubated above twenty-nine degrees Celsius become females; below that, males. They hatch in four to eight months. The baby tortoises toddle around in bird- and rat-proof enclosures. At about the age of five years, they can fend for themselves and return to their home island. So far, the Darwin Center has repatriated about 3,000 tortoises.

Today, the tortoise’s number-one enemies are goats. Once released freely as a source of meat for colonists and visiting sailors, goats now devastate the vegetation, starving the tortoises and robbing birds of nesting sites. The Galápagos National Park runs a goat-eradication project. One technique they use is the Judas Goat.The Judas Goat is tracked until it finds a population of goats. The biologists shoot all but the Judas Goat, who is left to find another group. The GNP always gets their goat.

In in a few spots, you can still see tortoises in something like their former numbers. My group visited one, called Galapaguera, on San Cristóbal Island. It is a giant, shallow collection-bowl for precious rainwater. Tortoises gather there like butterflies at a rain puddle. Fifteen of us made the long, hot, lava-strewn hike, single file. In the annals of our voyage, this leg is known as the Death March. On we trudged, chanting dirges, sucking Gatorade. The skulls of murdered goats adorned the trees, like grisly love-children of Charles Darwin and Georgia O’Keefe. After ninety minutes, we spotted reptile tortoise tracks.Two hours in, we glimpsed dome-shaped forms in the brush. The farther we walked, the closer they got to our path. Many have a number painted in white on the back of their carapaces, a reminder that these animals are wild, but monitored. At two and a half hours, one blocked our way, an object lesson in the subtle difference between arrogance and oblivion. He yawned. Someone took a picture of his tongue.

When at last we achieved Galapaguera, we saw what appeared to be a Martian lake. It was empty, dry, and, it seemed, tortoise-free. Then someone spotted a lone dome. And another. Out on the heat-shimmered, bone-dry lake, tortoises appeared spontaneously, like bad special effects. Under the trees, there were three—no, five—just a few feet away, staring at us. We were on the edge of a field of perhaps thirty tortoises. When rainwater collects here, there may be a hundred. They have been gathering here for millions of years.

My Gatorade ration, too, was drying up. I retreated into the mottled shade, where I tried to catch a tortoise’s eye. Three animals were in the heat of a slow-motion battle over squatter’s rights to a spot under a leafy tree. One hissed and growled at the others. One took evasive action. One raised his neck in defiance. None paid me any mind.