(1) Kelly Clarkson, “Already Gone” (from All I Ever Wanted, Sony BMG). Sometimes you want singers to wear their hearts on their sleeves. Especially when they sound like Sarah McLachlan.

(2) The Missing Person, written and directed by Noah Buschel (The 7th Floor). Matching its center of gravity—the way that with every scowl directed outward at the world Michael Shannon’s private eye pulls more deeply into himself, as if he can make himself his own black hole—the movie itself is dark and muffled. It’s hard to see and hard to hear. The plot is full of dead ends. But there is one moment of clarity, so full of unguarded warmth it seems to be from another film altogether, or another life: the detective and a woman who’s picked him up in a bar dancing in a crummy Los Angeles hotel room as the radio plays the Jive Five’s 1961 “My True Story.” “But we must cry, cry, cry,” Eugene Pitt sings, going up high, turning the swamp of the past into at least a hint of a future, and you think, yes, tell this story—while at the same time you’re wondering, OK, a thirty-five-year old Jive Five fan, he’s from New York, I can believe that, but how did he find a doo-wop station in California?

(3) Punk shoes from Giovanna Zanella (Castello 5641, Calle Carminati, Venice). Six-inch heels on black pumps with a Doc Martens sole and a red Mohawk that looks more like a weapon than a haircut coming out of the back.

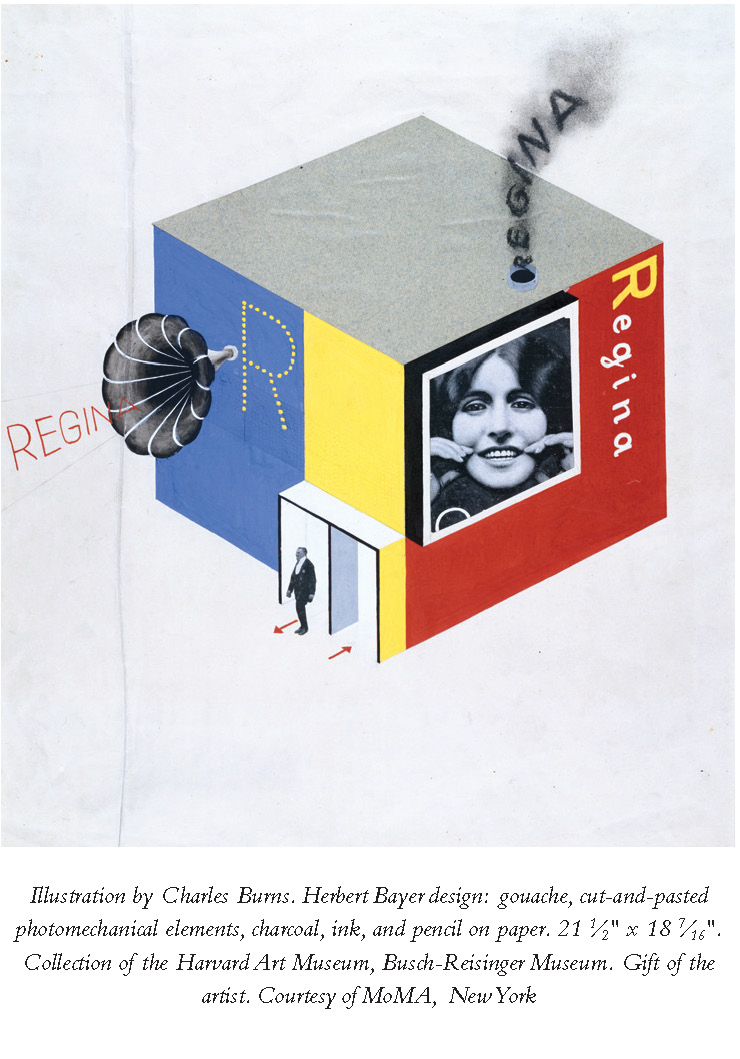

(4) Herbert Bayer, Design for a Multimedia Building, in Bauhaus 1919– 1933: Workshops for Modernity (Museum of Modern Art, New York, through January 25). It’s all Regina all the time: on one face of the rectangular box, a fi lm projected from inside showing Ms. R. pulling her lips apart in a happy if brainless smile; on another, a huge gramophone horn protruding, broadcasting the new hit “Regina.” On the roof, a smoke hole emitting small black clouds that spell out… you guessed it. To the side of the horn, under an overhang, a man exiting, while the diagram helpfully indicates the In and Out. The whole looks like a valentine from Bayer to his girlfriend Regina, a modernist treehouse, or a De Stijl–infl uenced mock-up of an ad for a freestanding one-woman brothel. The playfulness and glee of the design perfectly catches the thrust of the exhibition as a whole: the story of adventurous, questing, ambitious people with their lives and a world to change before them, about to be crushed.

(5) Jenny Diski, The Sixties (Picador). If you liked An Education and were wondering what happened next…

(6/7) Bob Dylan and Dion, United Palace Theater (New York, November 17, 2009). The stage was pure House of Blue lights before Dylan came on: deep velvet background, upside-down electric candles ringing the top of the stage. In that setting “Beyond Here Lies Nothin,’” from Together Through Life last spring, was a sultry vamp from a ’40s supper club. Clearly the song was still opening itself up to Dylan; he sang with heart, as if looking to find how much it might tell him. “Dedicated to our troops,” Dion had said earlier, for “Abraham, Martin and John,” and the mood Dylan was creating was already too fi ne for “Masters of War”; instead he sang the mom-sends-son-off-to-glory-and-then-he-comes-back folk song “John Brown” in a hard-boiled voice, the Continental Op running down the murders in Red Harvest. Most striking of all was “Ballad of a Thin Man.” In Todd Haynes’s film I’m Not There, Cate Blanchett, as Dylan in London in 1966, acts out the song standing alone behind a mic stand like a nightclub singer, no protection of a guitar between performer and audience. It was something Bob Dylan had never done, but that was precisely the posture he assumed now, as if the movie had taught him something new about his own song: how to make it more intimate, more direct, so that it was the audience, not the singer, that was left more naked, more defenseless. For all that, Dion stole the show. He opened with Buddy Holly’s “Rave On”—and that had to be to remind both Dylan and the crowd of the night in early 1959, just days before Holly died, when a seventeen-year-old Robert Zimmerman sat in the Duluth National Guard Armory, Holly himself sang “Rave On,” and Dion was an opening act at that show, too. Now he was seventy, and his voice grew, opened, gained in suppleness and reach with every song. One by one, he put the oldies behind him, so that it all came to a head with “King of the New York Streets,” from 1989. It’s a gorgeous, panoramic song: a strutting brag that in the end turns back on itself, a Bronx match for the Geto Boys’ “Mind Playing Tricks on Me.” It opens with huge, doomy chords, wide silences between the notes, creating a sense of wonder and suspension, and you don’t want the moment to break, for the music to take a single step forward—just as, after the song has gone on and on, you can’t bear the idea that it’s going to end. From that almost-frozen beginning, the pace seemed to speed up with every verse, but it wasn’t the beat that was doubling, it was the intensity and the drama. Dion’s wails were as fierce as ever, but never so full of wide-open spaces, the voice itself an undiscovered country, and it was impossible to imagine that he had ever sung better.

(8) Gov’t Mule, “Railroad Boy,” from By a Thread (Evil Teen). Upsetting a trainload of expert grind-it-out, the centuries-old melody and story of “Railroad Boy” (a.k.a. “The Butcher’s Boy”), which sounds like the precursor of the Teen Death Song: “Tell Laura I Love Her,” “Last Kiss,” “Teen Angel,” but perhaps more to the point, “I Don’t Like Mondays,” “Endless Sleep,” and most of all “Ode to Billie Joe.” Ruth Gerson made the connection explicit in 2008 with her Deceived; in Gov’t Mule’s hands, or hooves, it sneaks up on you like a villain in a Scream movie.

(9) Malcolm McLaren, Shallow (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, October 24, 2009-January 3, 2010). Twenty-one “musical paintings”—which is to say, loops of found footage depicting people gearing up to have sex with soundtracks made up of smeared pop songs, snatches of interviews or spoken-word performances, and swirls of movie tunes. “No matter how shallow people say pop music is,” McLaren writes in his exhibition note, “it continues to confound, astound, and seduce something deep in all of us—the desire to change the culture and possibly, if it be only for a moment, change life itself. No matter how shallow people say sex is, it continues to occupy and post-occupy everyone’s thoughts, forcing us to be irresponsible, childish and everything this society hates, and why not?” A topless blonde woman descending a staircase and dragging a fur coat behind her as Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” answers Captain and Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together” is a joke that never comes to life. There’s a shaggy, fleshy guy with his arm draped around a grinning beanpole; they don’t seem to be listening to the bits of the Staple Singers’ “Respect Yourself” floating in and out of a disco version of an old country blues, and when the camera pulls back to show a handgun jammed into the front of the second man’s pants, you don’t hear the music either, because now the man’s faraway resemblance to Timothy McVeigh is undeniable. Best of all is a dressed-up seventies couple, seated on a couch, apparently watching a movie on TV, both smoking, with fragments of the Zombies’ “She’s Not There” circling their heads. It’s super-slow motion; the slightest change in expression becomes an event that you follow in a state of suspense. As the man steals glances at the woman with a self-satisfied smile crawling over his mouth, her eyes widen in an expression of surprise or fright that imperceptibly but definitively changes into arousal, and then the sequence begins from the beginning. You watch them again and again—and then fi nally McLaren allows the fi lm to go a step further. The man is still contemplating his conquest, the woman is still lost in her own world, until she turns her head and sees him, her eyes as clear as if she were speaking out loud: Who is this guy? Where did he come from?

(10) Ed Sullivan’s Rock and Roll Classics: The 60s (PBS, November 29). Fund-raising break commentary by host TJ Lubinsky: “Public television has always been there as an alternative to”—the Ed Sullivan Show?