Destroy This Mad Brute: The African Roots of World War I

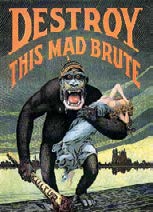

The hundredth anniversary of the start of the First World War, currently being observed pretty much everywhere, has poured forth a whole variety of stark and sobering images, but the one that really startled me the other day was that of a US Army enlistment poster from 1917, fashioned by the noted stage designer H. R. Hopps and in turn based, we are told, on a whole slew of British propaganda images from earlier in the war: a huge, hulking, drooling man-ape, capped by a pointed Kaiser-helmet (labeled MILITARISM), with one arm wielding a mammoth club (labeled KULTUR) and the other gripping a half-naked, fainting maiden, lumbering out of the sea onto dry land (labeled AMERICA). The abject ruins of his European depredations smolder in the far distance behind him: “DESTROY THIS MAD BRUTE” implores the none-too-subtle poster’s none-too-subtle headline. And we are off: welcome to the rest of the century.

It was the sheer incongruity of the Germany-as-African-gorilla motif that first got to me, but as the weeks passed, the twisted visual rhyme came to seem somewhat more apt: I’ve been thinking a lot about the African roots of the First World War, or rather the ways in which Europe’s ever more grotesque and monstrous depredations across that continent, especially toward the end of the nineteenth century, set the tone for everything that was to follow back in Europe during the next. World War I can be seen in this light as an instance of karmic blowback, with Europeans simply starting to do to each other what they had already been doing to Africans for some time—which is to say, starting to see each other in the same kinds of barbarian, subhuman terms they’d once lavished upon their colonial subjects (the sort of terms that had in turn allowed them to innovate in Africa the barbed-wire trench warfare, mass machine-gun embankments, concentration camps, and the like that now made their way back to the home continent). In this regard, things weren’t altogether unlike what had happened earlier, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially during the unbelievably gruesome Thirty Years’ War, when Europeans simply took to launching the kinds of religious crusades against each other that they had earlier foisted upon the Muslim Arabs of the Middle East.

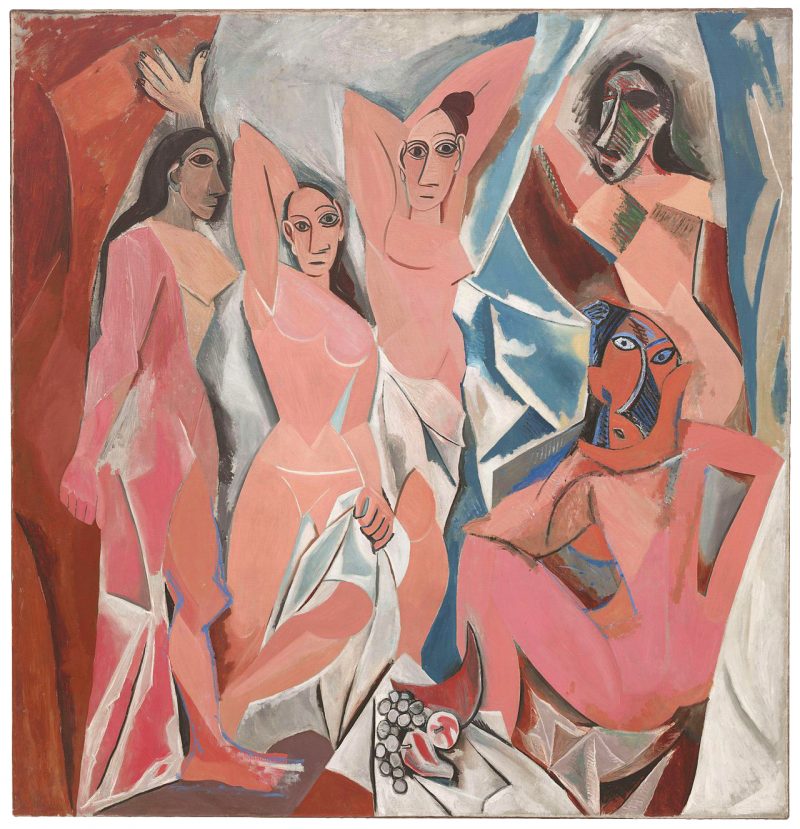

For that matter, much of the moldering cultural and even scientific ferment that characterized the first decade and a half of the twentieth century, and that laid the foundations for much of what we consider “modern” today, can be traced back to the ways in which Europe was already wrestling with its bad-faith (and often strenuously repressed) knowledge of what it had been doing in Africa. The example of Picasso virtually launching cubism with his 1907 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, in response to the sorts of African masks and other colonial booty he was encountering in Paris’s Musée de l’Homme, is obvious.

Not so much so, perhaps—though every bit as pertinent—was the occasion for Einstein’s derivation of the theory of relativity at almost exactly the same time. Until recently, the sense most people had of the young Einstein during his late twenties was of a secret genius wasting away the hours in a stultifying day job in the Swiss patent office, following which, in the evenings, he set his mind to revolutionizing the history of science. But a few years ago, historian Peter Galison, at Harvard, had the wit to investigate what exactly had been coming over the young Einstein’s desk there in the Bern patent office, and it turned out that the hot technological challenge of the time, especially there in clock-obsessed Switzerland, was the determination of simultaneity.

It wasn’t enough for clocks to become ever more exact; the goal was to find a way of making sure that the time on one clock registered absolutely identically with that on another clock at a considerable distance from it (by no means a simple matter, since even a near-instantaneous electrical signal took a certain amount of time to travel from one to the other), dozens of patents were being filed for devices claiming to calibrate that minimal disjunction to ever more exacting degrees—and it was precisely reviewing those claims that was the young Einstein’s daytime job. In the evenings he merely continued puzzling over the dilemma, presently coming to realize that the very concept of absolute simultaneity

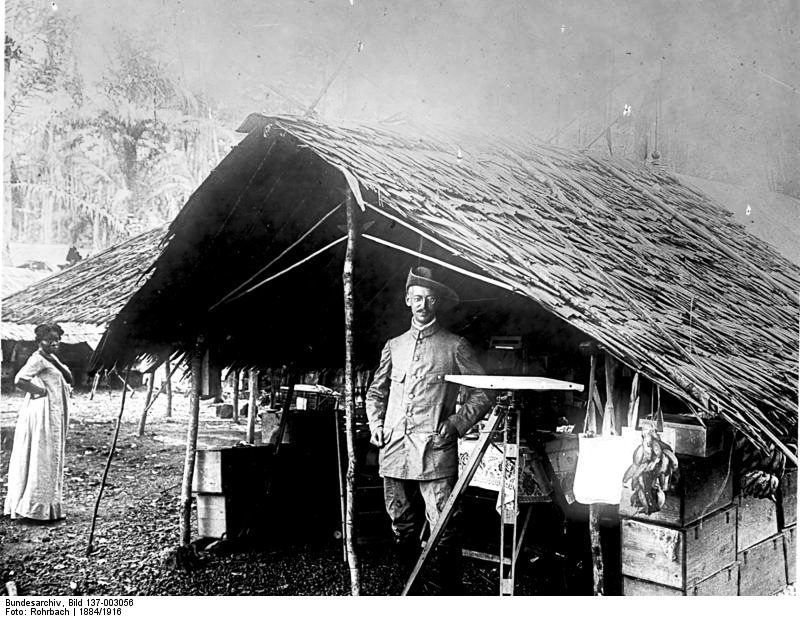

was an impossibility; that all such claims needed to be made relative to some specific point of vantage… and so forth. But the point here is: what was the technological urgency around the need for such simultaneous calibrations at that particular historical moment? And there, as Galison demonstrates in his 2003 book, Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps: Empires of Time, the answer was the race among Europe’s colonial aspirants to partition Africa (and other far-flung territories more generally), a race in which all surveyors operated on Greenwich mean time, but therefore needed to make sure their watches, deep in the almost-impenetrable jungle, were synchronized with the master clock in Greenwich, at the risk of otherwise getting the resultant borders wrong, errors regarding which (especially in the context of the rush for mineral rights) could easily lead to bloodshed.

Or Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring—and here we get closer and closer to the outbreak of the European war—with its calamitous Paris premiere, in May 1913.

In the past, musicologists have been fond of insisting that those pounding, pulsing, percussive syncopations at the outset of the Rite, and later on during the “virgin sacrifice” passage, merely referenced Russian folk melodies from Stravinsky’s youth. But more recently, and especially at a “Reassessing the Rite” conference held at the University of North Carolina on the occasion of that one-hundredth anniversary, younger scholars such as Annegret Fauser and Brigid Cohen have suggested that those passages were directed at a more localized Parisian and cosmopolitan taste for exotic primitivism, which is to say the lurid fantasy of naked, polymorphous, pagan Africa bleeding through.

“Black and hideous to me,” a seventy-one-year-old Henry James wrote his friend Rhoda Broughton on August 10, 1914, “is the tragedy that gathers, and I’m sick beyond cure to have lived on to see it. You and I, the ornaments of our generation, should have been spared this wreck of our belief that through the long years we had seen civilization grow and the worst become impossible. The tide that bore us along was then all the while moving to this as its grand Niagara—yet what a blessing we didn’t know it.”

Which is fine as far as it goes—but really? “…we had seen civilization grow and the worst become impossible.” How blinkered did one have to be not to see how that glorious civilization was grounded in and permeated through and through with the hideous violence visited upon the outlying millions of its colonial subjects, especially in Africa? And yet James was hardly alone in such willfully maintained obliviousness. In fact he and Broughton were unusual, there in 1914, only in being appalled by the nationalist (tribal) bloodlust suddenly surging through the respective body politics all around Europe. Almost everyone else, it seemed, whether in Vienna or Paris or Berlin or London, seemed positively ecstatic at the approach of war, likening the prospect to a good, swift, purging summer storm, one that would quickly wipe all the brooding, stultifying moral languor (over what, exactly?) clean away—and this was a mood, a temper, a distemper, that cut clear across class and political lines (each separate party in the supposedly pacifist Socialist International rushing to the support of its respective national war machine right alongside everyone else).

My Viennese grandmother, Lilly, used to marvel at it, recalling the war hysteria into which she herself had been lifted, “exalted,” as she put it, during those first few months of the war. And her Viennese husband, the (subsequent) Weimar-era and then Hollywood émigré composer Ernst Toch, years later would record his own exaltation as a fervent inductee and its consequent shattering as he frog-marched into the debacle of the Austro-Italian front (in what is now Slovenia, the same front across the lines of which Hemingway spent his ambulance-volunteering months in A Farewell to Arms) in his autobiographical 1954 Third Symphony. I wish I could play it for you (in fact, I can: find a link to it at blvr.org/toch): the rousing martial parade, the surge toward battle, the calamitous engagement, and the final descent into an agony of dissonance.

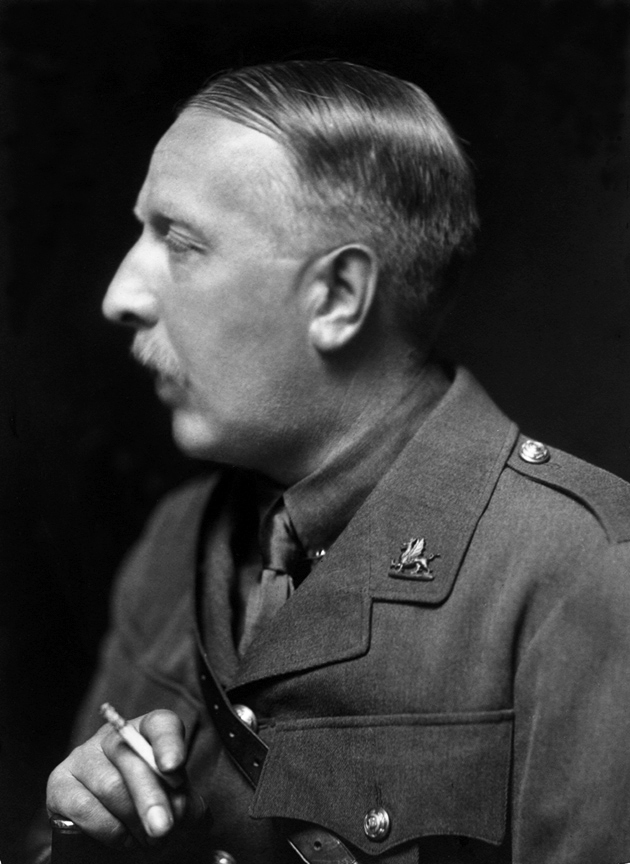

Ford Madox Ford, James’s friend, though thirty years his junior, got it exactly right, both in his The Good Soldier, written before the war but not published till 1915, with its eviscerating portrayal of the moral obtuseness of the very same prewar, spa-languoring class James so lauded in his fantasy of compounding civility, and then, even more so, in his Parade’s End tetralogy, especially in the first volume, Some Do Not…, with its limning of a social class veritably crawling out of its own skin at its suffocating conventions and insufferable pieties, just waiting, desperately, longingly, for something, anything, to happen.

But then again it was Ford Madox Ford, several years later, in Great Trade Route, his 1937 volume of miscellaneous thoughts, surmises, and recollections (written immediately following Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, and clear-eyed about all that that development portended), who retrospectively nailed it when it came to what had truly brought on that August 1914 conflagration (curdled social longings notwithstanding). Typically, he inched toward his thesis tangentially, first recalling a story about how Walter Raleigh had once told Lord Chancellor Francis Bacon (“who was a grafter compared with whom many of our overlords today were mere beginners”) about his intention to set out on a last expedition to “the Indies” (i.e., the Americas), and how “if he failed to find the famous and fabled gold mine of the Orinoco that he purposed finding, he intended to set about the Spanish treasure ships in returning” so as to be able to lay at the feet of their sovereign, James I, untold troves of riches. “Lord Bacon,” Ford continues, “expressing the utmost horror, exclaimed that it would be rankest piracy…. ‘The rankest piracy,’ said the Lord Chancellor. But no, answered Raleigh, if you take millions it is not piracy.”

And with that speech, Ford went on to observe, “Raleigh withdrew the curtain that concealed the New World from the Old”—by which, he says, he doesn’t mean the Western from the Eastern Hemisphere, but rather “the millions of years that preceded from the three centuries that have since lapsed,” which he goes on to characterize as the age of mass production and of the “Moloch Machine” (Moloch having been a human-sacrifice-demanding idol referenced in the Old Testament) with its “stealing-a-million-isn’t-piracy psychology” that was “bringing about our ruin. We appear, as a civilization,” he concludes—and remember, this is 1937—“to be about to go down in flames. The immediate cause seems to be that our Italian kinsmen think that, sheltered behind the Machine, they will be able to do what no other race ever accomplished… steal millions with impunity from Africa. It can’t be done.”

Line break. And then a simple one-sentence assertion:

“The partition of Africa which went on between 1882 and 1914 was the occasion of what happened in that latter year… and ever since.”

After another line break and a bit farther on, there follows one of the meatiest, most revealing footnotes I’ve ever encountered, over half a page long, in which Ford lays out “the salient dates as follows,” with one leapfrogging incident following the next, from March 1883 through the Berlin Conference of 1885 and the mad scramble it both codified and further sanctioned, through the French annexation of Madagascar, in 1896, the Fashoda Incident of June 1898, which set Britain and France “within an inch of War,” the Transvaal’s October 1899 invasion of Britain’s South African possessions and the three-year war it provoked… and on to 1911, when “for several months France and Germany at Agadir were within an inch of War over Morocco. Under cover of that tension, Italy declared war on Turkey with the intention of annexing Turkish N. Africa. This led directly to the first and second Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913… And those wars, by bottling up Germany from the Near East, led directly to her invasion of Belgium of 1914.” And that’s barely the half of it.

Germany’s invasion of neutral Belgium, in 1914, was a necessary component of its army’s all-encompassing, preemptive Schlieffen Plan, with its sweeping, right-flanking maneuver, albeit one that thereupon forced treaty-bound Britain’s entry into the war, or so the British propaganda office preferred to frame matters thereafter. “The Rape of Belgium,” “Poor, pure, innocent Belgium,” and so forth. Hence much of the imagery (including the fainted damsel in the monster’s grip) that would come to find its way into Hopps’s US Army recruitment poster a few years later. The exact degree and character of all that violence have been matters of heated dispute among historians over the decades since: for her part, the historian Nicoletta Gullace parsed matters with near-Solomonic even-temperedness in 2002 when she wrote that “the invasion of Belgium, with its very real suffering, was nevertheless represented in a highly stylized way that dwelt on perverse sexual acts, lurid mutilations, and graphic accounts of child abuse of often dubious veracity.”

Suddenly Hopps’s 1917 poster, with its no longer quite so incongruous Gorilla Hun, begins to ramify in all sorts of directions, welling up a veritable tantrum of associations.

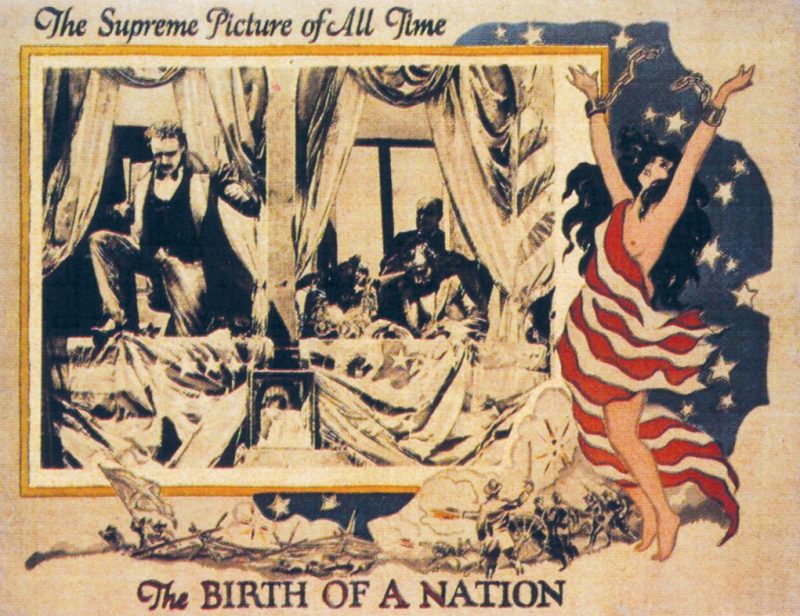

For starters, to the specifically American racist tradition of portraying black people—the descendants, that is, of African slaves (our own African depredations several generations removed)—as themselves lumbering apes. And from there of course to that other signal milestone of modernism, D. W. Griffith’s rabidly racist The Birth of a Nation, from 1915, only two years earlier. A favorite of that good Southern president Woodrow Wilson’s, Griffith’s film climaxes with phalanxes of white-hooded Klansmen riding to the rescue of embattled white women, pure flowers of a resurgent South, to the rousing accompaniment of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries,” of all things—Kultur, indeed. All of which sort of short-circuits Hopps’s iconography, while at the same time grounding it.

And then, as well, to the cinematic spectacle King Kong of a few years later, 1933, veritably pullulating in its own psycho-racial-sexual confusions, quoting Hopps’s poster almost verbatim in its own most memorable moment:

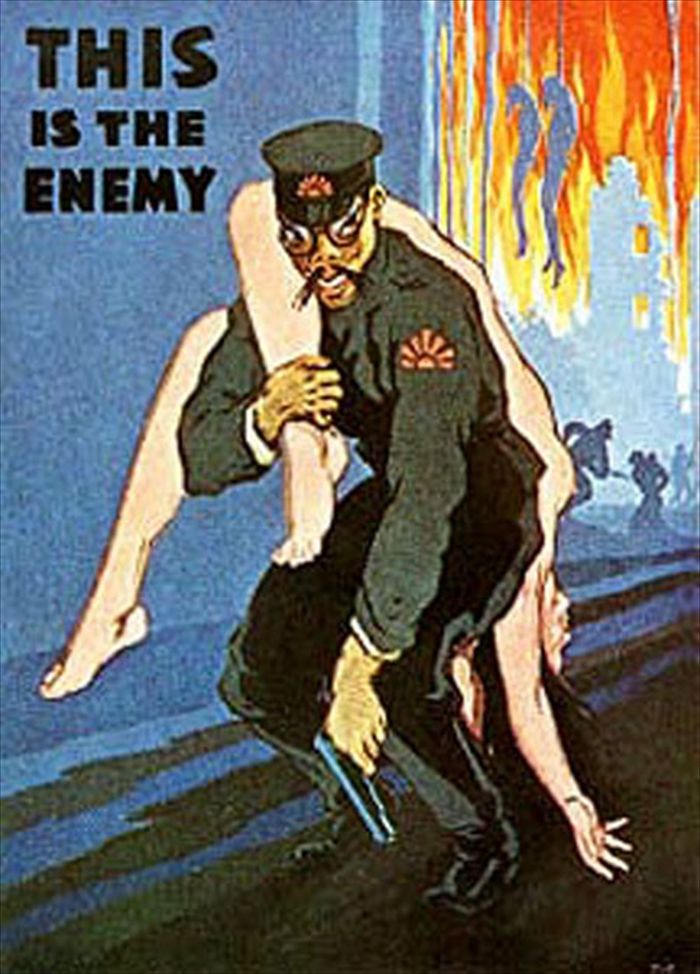

But then to the way that the Germans after 1933 reveled in flipping the polarities of the Hopps poster, such that now it was the disgusting British/American/Soviet/Jewish apeman to come lumbering forward, intent on defiling the purity of the Reich:

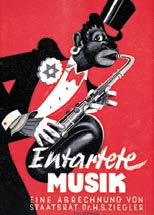

And it was lascivious, monkey-lipped African American saxophonists with Jewish Stars of David in their lapels slavering all over the pure Aryan tradition in special demonstration concerts of their Entartete Musik, their “degenerate music” (my grandfather, safe in his California exile, having been both grieved and proudly affirmed to be among those featured—having for that matter hit the jackpot of being represented as an ape twice: as a German in one war and as a Jew in the next).

And for that matter many of the obverse propaganda characterizations that came to dominate American wartime propaganda vis-à-vis their Japanese opponents:

And all of it wending its way back to our friend the Gorilla Hun. The Other as subhuman, and hence all the easier to vilify and massacre without heed: truly another signal invention of modernism. And that, too, wending its way back to Africa.

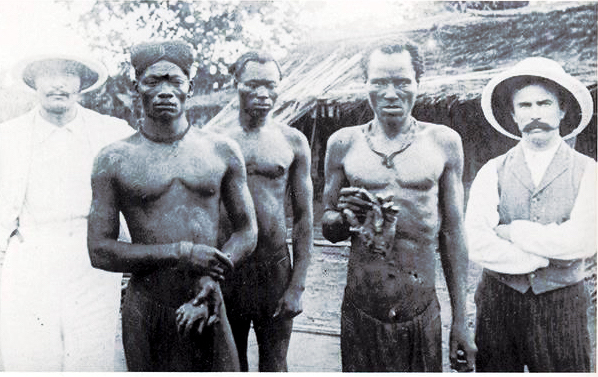

For look again at pure, innocent Belgium aswoon there in the great ape’s fiendish grip. Destroy the Mad Brute, indeed, but where does that line come from? From no one other than Joseph Conrad (another dear friend of Ford Madox Ford’s) and his 1899 novella Heart of Darkness, arguably the single greatest harbinger of the coming century, with its characterization of that ur-European, the onetime would-be civilizer Mr. Kurtz, who ends his days plying his trade in arguably the single most vicious and vile colony of them all, the Belgian Congo, utterly depleted, completely demented, footnoting his own report: “Exterminate all the brutes!”

The horror, the horror.

See print version for photo and image credits.