Figes

I bought the book for a dollar and a quarter at Community Thrift on Valencia, in San Francisco. I can’t recall when. I’ve bought so many books for a dollar and a quarter at Community Thrift. It might be—no offense to my friends at Dog Eared—the best used-book store in San Francisco, if you judge only by prices and the randomness of the selection. In any case, I’ve held on to it for many years without reading it. You know the kind of books I mean? The books you are waiting for the right moment to open—though what you mean by “the right moment,” you’ve got no clue?

It’s called Light: With Monet at Giverny, and it’s by Eva Figes, a German-born British novelist who died in 2012. This past weekend, for inexplicable reasons, after making a conscious effort not to read the book for so long, I found myself holding it. I sat down on the floor. I read a little. The book is about an elderly Monet in his garden at Giverny. It opens with Monet awake before dawn:

The sky was still dark when he opened his eyes and saw it through the uncurtained window. He was upright within seconds, out of bed and had opened the window to study the signs.

On this day the light seems to him promising and so he hustles to bathe and have breakfast so he can get outside and catch it. This isn’t so easy. Getting Monet out the door entails the hustle of numerous servants as well—the woman who serves him breakfast, the man who rows the painter out to his little island studio. It’s clear that Monet wasn’t easy to work for, and was often, at best, indifferent to his family. But what’s entrancing about the book’s opening is that you start to feel giddy along with Monet. What he’s after this morning is not the sunrise, but the moments just before. In fact, when the light does arrive (“Everything would change now”), it wrecks the scene completely. The book is pervaded by this desire to harness the fragile fraction of time before the sunlight begins to touch the trees. Maybe this is what I craved without knowing it? Too often I wake up late and even then I’m almost too tired to face the morning light. Look, I’ve never believed in books as forces of healing. As much as I live for them, breathe for them, they are only, at the end of the day, bound paper and glue. I don’t want to get at all cosmic here. And yet. Maybe it’s possible that certain books stick around and wait for a reason. Maybe they ache to tell us something? In this case, a book held its tongue for years until my fingers finally pried it loose from between two other books, where it had probably been lodged since 2004.

Hey, Orner, yeah, I’m talking to you, you lazy fuck. Pay attention to the dawn.

It’s the story of an artist for whom light is everything, but who wants this morning, above all, to slow down its arrival.

Something still eluded him, though now, with time running out, he thought he had almost got it. Soon dawn would come, and with it would go this hush, this cool luminosity coming through stillness. It was like sitting in the calm center of the world, he thought, this total balance between the world and its mirror image, water and sky.

I have no idea how Eva Figes came to write this book, which apparently is unlike anything else she wrote. I don’t much care. What matters is that it exists, and that it was there when I reached for it two days ago. Mercifully, the book jacket tells me nothing. I don’t know if she read biographies of Monet or stood in a museum, and for hours studied Monet’s paintings. Probably Figes did both. But at a certain point, I imagine, she must have gone out in the blue predawn unlight and just breathed.

Miller

Reading Death of a Salesman the other day, I was struck by the character of Charley, Willy Loman’s Brooklyn neighbor. Charley plays the straight man to an increasingly unhinged Willy. There’s a suggestion that the two men are related, which would explain why Willy’s hostility toward Charley coexists so seamlessly with his willingness to constantly hit him up for money. Charley doesn’t have many good lines compared to Willy, Linda, and Biff. (Happy, Willy’s younger son, you’ll remember, is mostly ignored by the other characters. In my family, I’ve often assumed Happy’s role.) Charley, in contrast to Willy, represents the sort of father who does right by his kid. He’s not pushy. Unlike Willy, Charley doesn’t dream big through his son Bernard. For instance, Charley encourages Bernard to study (or at least doesn’t discourage him). Willy, on the other hand, ascribes to the American cult of trying to be liked. Books will get you only so far. But according to Willy, you can’t possibly go wrong if you’re well liked.

Willy: That’s just what I mean. Bernard can get the best marks in school, y’understand, but when he gets out in the business world, y’understand, you are going to be five times ahead of him. That’s why I thank Almighty God that you’re both built like Adonises. Because the man who makes an appearance in the business world, the man who creates personal interest, is the man who gets ahead. Be liked and you will never want. You take me, for instance. I never have to wait in line to see a buyer. “Willy Loman is here!” That’s all they have to know, and I go right through.

Biff: Did you knock them dead, Pop?

Willy: Knocked ’em cold in Providence, slaughtered ’em in Boston.

It’s notable that no matter how much I root for Willy, it’s almost impossible for me to believe that the man, even in his prime, was ever an especially good salesman. He never once mentions what it is he actually sold. He got the job done, whatever it was. The whole point is that he didn’t have to be great at it. Willy Loman made a living. But now that he’s older, he can’t pull his own weight anymore. And yet because Charley is Willy’s foil—he’s successful, modest, not a blowhard—he comes across as dull. So it’s a relief when, late in act two, it is Charley who delivers what are, to my mind, some of Miller’s great lines:

Why must everybody like you? Who liked J. P. Morgan? Was he impressive? In a Turkish bath he’d look like a butcher.

“In a Turkish bath he’d look like a butcher.” When you see the play live, this line always gets a laugh. At that moment, you need it: Willy’s desperation is almost too much to take. He’s in retreat and inching closer and closer to suicide. Not only does the line redeem and enrich Charley’s character, it also cuts to the heart of Miller’s critique of an America that chews up and spits out Willy Lomans by the mouthful. And let’s be honest, aren’t we all complicit? Don’t most of us, in our own ways, chew up Willy Loman and spit him out? We might like to read about lovable losers in literature, but in life? The truth is, we can’t abide them. We never have. In spite of everything. Losers? In this country of bottomless opportunity? And the last thing we want to accept is a loser in our own family. It’s as inexcusable today as it was when Death of a Salesman premiered, in 1949. Success is our only measure. Just in case the audience doesn’t get it, Miller has Charley add: “But with his pockets on he was very well liked.”

Nearly ruins it. (It’s the “on” that saves the line from being overkill.) But for me, J. P. Morgan in the bath is enough. That naked, bloated body is enough. He’s no Adonis. But when you’re richer than God, you can look like anybody, even a butcher. It’s telling that Willy’s so far gone by this point that he doesn’t laugh.

O’Connor

I came across a line the other day in Clout: Mayor Daley and His City, Chicago journalist Len O’Connor’s 1975 book about Mayor Richard Daley and the idea of power in Chicago. O’Connor makes a brief mention of Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, calls him “a sad little guy with one kidney and a calculator in his head.” This got me remembering. I grew up hearing about Greasy Thumb Guzik. Jews in Chicago like to hear stories about our gangsters. See: we weren’t always dentists and lawyers. But it’s said that Guzik never carried a gun. He never needed to. He carried numbers, figures, which were infinitely more powerful. Guzik was Al Capone’s accountant. Italians always had to have at least one whiz-kid Jew to look after the finances. Their own whiz kids became monsignors. Like in the movies. In addition to the numbers in his head, gunless Guzik was said to walk around with at least ten thousand dollars in cash. That way if he got nabbed he could always buy himself back. Ten grand insured he’d have a few bucks left over for a steak and cab fare home. The headline writers loved to give him names. Little Fella, Top Noodle, Panderer in Chief, Old Bossy Eyes.

He called himself Jack Arnold, and he told the Kefauver Crime Committee he was retired. “Retired from what, sir?” a senator asked. Guzik declined to say, on account of his Fifth Amendment right not to criminate himself.

When he died, obese, in 1956, they had to hold the funeral in Berwyn, Illinois, because if they’d held it in Chicago, more than half of the mourners would have been arrested. Mae, Al Capone’s widow, made the arrangements, and the rabbi solemnly declared that Jake Guzik never lost his faith in God. “Hundreds benefitted from his kindness and generosity. His charities were performed quietly. And he made frequent and vast contributions to this congregation…”

Which brings me to this story about Greasy Thumb and my uncle Erwin. The details are vague, but one day, my grandfather used to say, Erwin was having lunch by himself at Fritzel’s when Guzik waddled by his table. Something about my uncle caught his eye. And Guzik said: “Aren’t you a melancholical bastard?”

Maybe he saw a kinsman? It wasn’t simply that Erwin was a fellow Jew. Fritzel’s was packed with Jews. It was that my uncle had that familiar mournful look. A gloomy countenance. Guzik could spot a man burdened by troubles: there’s somebody you can trust. The sort of man who won’t stab you in the back the first chance he gets. Useful. It was the 1940s. My uncle would have been in his early twenties. Could have been the chance of a lifetime for a kid without prospects. They hadn’t let Erwin go off to war, my grandfather said, due to his “limitations in the head.” But Uncle Erwin didn’t know who the fat man was. Nor did he much care. He was, in his sad way, enjoying his sandwich.

“Kid, you need something? What can I do for you?”

How often does power not seduce? O’Connor says that in Chicago, people used to say, “Who’s your clout?” And here was a big man, one of the biggest, offering up himself, no strings attached. Not yet, anyway. You want people to be beholden. Uncle Erwin only stared at his corned beef sandwich. He took another bite. For a moment Guzik thought the kid might be razzing him. In Fritzel’s, he was accustomed to fealty, especially among his own populace. But this one was for real, melancholical. Guzik dug around in his pocket for his colossal wad, peeled off two tens, set them beside Erwin’s coffee, and waddled onward.

Hoffmann

In The Book of Joseph, Yoel Hoffmann writes:

And the photographs a person leaves behind are not enough for consolation. It would have been better to go away without leaving any trace…

Hoffmann is an Israeli novelist, Romanian born. Writes in Hebrew. In addition to writing fiction, he also translated a classic book about Zen Buddhism and wrote a study of Japanese death poems. Too few readers have heard of him. I have it on good authority that Hoffmann doesn’t give a damn. To read him is to have an intimate conversation with an elusive friend, the sort of friend you meet only by chance—but whenever you do, he always whispers in your ear something you’ll never forget. Hoffmann’s novels are surprising, funny, lyrical, radically concise, and somehow buoyant and heavy at the same time. By this last contradiction I mean that the seeming weightlessness of Hoffmann’s prose has a weird effect. He makes me feel alive, a little lighter on my feet, and yet as soon as I feel that rising, I’m all the more conscious of my gravity.

Today, in a notebook, I found the above quote about the uselessness—and worse—of photographs, and it reminded me of a picture I have somewhere of L at Half Moon Lake, Michigan. Every once in a while, I come across it in a drawer among stray papers. I always wish I hadn’t. But I never just toss it. I always shove it back into the drawer and hope it gets lost for good this time. It must have been a windy day. L’s hair is rising over her shoulders in a kind of swirl. She’s squinting because she’s looking directly into the sun. She’s wearing a white shirt with big buttons. The front pockets are closer to her waist than her chest. A man’s shirt? Whose? Far too big to be mine. She’s wearing cutoff shorts. Is she holding a flower? Now I can’t find the picture to check. I can find it only when I’m not looking for it. I think she’s holding a flower, and she’s leaning against the hood of my aunt Gertrude’s Buick Century. The car was parked in Aunt Gertrude’s driveway when she died. My mom said, “Take it. Keys are on the hook by the back door.” L’s leaning against the hood of that Buick, her hair wild in the wind, holding—maybe it’s a dandelion? No, bigger. A sunflower? Her eyes are as blue as my father’s. You can’t see Half Moon Lake, because the car’s blocking it, but that’s where we were. That I know for sure. Did we swim? She’s not dressed to swim but that wouldn’t have stopped L. And she’d have ditched the shirt and cutoffs if nobody was around. I can’t remember. Maybe it was too cold. Whatever we did, later we drove my dead aunt’s car back to Ann Arbor and immediately, upon reaching L’s place on East University, ran upstairs and fucked like rabbits because L’s roommate would be home any minute. L would not approve of my relating this to strangers. But at a certain point, don’t the scraps of our lives enter the public domain? Forgotten Ann Arbor days—don’t they become history? L would also say emphatically that we never fucked like rabbits. L’s version is probably more correct. And yes, now that I think about it, I remember that before we went upstairs, she played a Taj Mahal record that had belonged to her father. By that point we were so exhausted from the sun and the drive that, behind the closed door of L’s room, we fucked like tired horses. Is that more accurate? I think I see what Yoel Hoffmann is getting at: that memory can cause physical pain and the last thing we need is this object, so flat and flimsy you can rip it up with your fingers, stabbing us in whatever heart we’ve got left. But even if a photograph gets lost, does it ever really vanish without a trace? I should say that the source of the quote that started this brief reverie, Hoffmann’s extraordinary short novel, The Book of Joseph, is more about sex than about the Holocaust, which makes it the saddest Holocaust book you can imagine. Not that he ever mentions the Holocaust. Hoffmann’s too good for that. There’s a great deal of sex, though. Sex and love and sex. And sex (and love), after all, is all (often, sometimes) about the contact of bodies. Hoffmann writes:

More than Yingele wanted to see Chaya-Leah’s face, he yearned to touch her body.

Hoffmann writes:

When Miriam is near him, Joseph’s body is fit to break.

Love and the body. Lose the body and all you’ve got left is the memory. Think of all the lost bodies. Which is why: to hell with the photographs. They’ll never be enough for consolation, because they will never be the bodies.

Leffland

Six months ago I left a novel on a train. I was on page 127. I always remember page numbers. I could order another copy online, as it’s not the sort of book I’d easily find on the shelves of even the most overcrowded used-book store. The copy I was reading was from the library at San Francisco State. At some point, I’ll have to pony up the money to replace it. The book itself was probably tossed out by a BART cleaner, at the end of her shift, in a hurry to get the train ready for another run from Richmond to Millbrae. Or maybe she stuffed it into her bag and took it home. I hope so. Anyway, I don’t want to find another copy. I want to keep reading the one I had. And I still am reading it. You ever had this feeling? That you don’t need the book to keep reading the book?

A young girl raised on a farm in the farthest reaches of Northern California, in the right-hand corner of the state that’s formed by the borders of Oregon and Nevada, leaves home at sixteen. Makes her way to San Francisco. It’s the mid-1930s. On Market Street, sidewalk shouters are preaching the virtues of the New Deal. The girl, Rose, finds a room in a boardinghouse in a shabby neighborhood, back when there was such a thing in San Francisco. (Now all we’ve got is Permit Patty.) To make ends meet, Rose finds a job at an insurance company. She falls in with a group of writers and artists. She herself aspires to write. She also dreams of one day saving enough money to ride the Trans-Siberian Railway. You think you have an idea where she’s heading. You think it might be rough, that reality will eventually overtake her dreams, but she’s going to be all right, this Rose.

But that’s not the way it goes. She goes out to dinner with her boss at the insurance company, a beyond odious figure named Mr. Leary, a man simultaneously attracted and repelled by Rose’s bookishness. After the dinner, in her room, Mr. Leary rapes her. Then, out of a kind of combination of fear and inertia, Rose continues to see him after work. She’s poor. She needs the job.

He’s rich. He’s married. He keeps coming to her room. She gets pregnant. He promptly fires her. After the baby, Gloria, is born, Mr. Leary refuses to recognize or support the child in any way. But Rose is tenacious and attempts to bring a paternity suit against him. In order to try and get her to knock it off, Mr. Leary returns to her room and threatens her. It’s winter, cold, the baby is crawling around on the floor. Rose throws something—I forget what—at Mr. Leary’s head. In the violent struggle, a gas heater topples over and falls on the baby.

It’s one of those moments in fiction. The sort you wish you hadn’t read, but now that you have, you’re going to carry it with you. Rose tries to remove the gas burner from the baby’s head, but she can’t; it’s too hot.

The book I left on the train was Ella Leffland’s 1970 novel, Mrs. Munck. Apparently, Diane Ladd made a movie of it in 1995. A comedy. The novel’s not a comedy. The numbness that Rose experiences following her daughter’s death is described in some of the most deeply disturbing and tormented prose I’ve ever read. So what happens next? Not too long after Gloria’s death—and this is where the book becomes as convoluted as only life can be—Rose marries an acquaintance from the insurance company who happens to be Mr. Leary’s nephew. The couple moves to a small house in what was then an underpopulated part of the East Bay, on the shore of the Carquinez Strait. This loveless marriage lasts decades, which Leffland, audaciously, compresses into only a few pages. Upon the death of her husband (whose first name I forget, he’s so irrelevant), Rose—now Mrs. Munck—decides it is time to take in a boarder. Why, what about her husband’s elderly uncle Mr. Leary, who’s lonely, languishing in a nursing home? After all, Rose is family. The rest of the book—and again this sounds convoluted, but on the page, somehow, it works, at least for the 127 pages I read—concerns Rose and her captive, Mr. Leary. (Note that Stephen King’s Misery, a book Mrs. Munck resembles in superficial ways, was published in 1987.)

Novelist and short-story writer Ella Leffland, who is now eighty-six and still writing fiction in the Bay Area, knows evil. In 1990, she published a seven-hundred-page novel about the life of Hermann Göring. Rose’s revenge in Mrs. Munck is as warped as it is justifiable. Like I said, I’m still reading it; I’m still trapped in that little house overlooking the Carquinez Strait. And I don’t want to be untrapped. Does this make any sense? I’m enjoying the dread, and the sweet, twisted vengeance. It goes on, and it goes on. Why do some books need to end? Lose them; they keep breathing. And Mr. Leary, wheelchair-bound and terrified, wonders if she’ll let him live another day.

Dickinson

I never get her poems. Nobody leaves me as grasping as Emily Dickinson. At the same time, I’m grateful she doesn’t spell it all out for dolts like me. Is there an American writer who speaks a more private language? I often wander around baffled by a phrase of hers. Today it’s:

Drowning is not so pitiful

As the attempt to rise

Brutal couple of lines, no? Write it in prose and it’s even rougher:

Drowning is not so pitiful as the attempt to rise.

For some reason—and it might just be me—I read Dickinson’s pitiful as close kin to pathetic. As in there’s something pathetic about someone drowning. Scholars (and biographers) say that something happened to Dickinson in 1860, around the time she turned thirty. Some cataclysm, rooted in unrequited love. In the past, it was believed that the love was for an unknown man. Now many believe it had to do with a certain woman. In any case, some say that around this time, Dickinson turned her need for physical love away from a human being and toward the page, with a vengeance. By 1865, Dickinson wrote nearly a thousand poems, half of her lifetime total. It might be fair to suggest that “Drowning is not so pitiful” is another intense manifestation of lingering despair over lost love. But it’s not Dickinson’s biography that interests me. I’m preoccupied by the lines themselves, this image of a drowning person attempting to rise. Now: if I’m drowning, I’m going to attempt to rise. Wouldn’t you? But if I’m drowning, I’m also drowning. Otherwise, I’d be something else, like “swimming for dear life” or “splashing around like a lunatic.” But if in fact I’m drowning then the show’s pretty much over. It’s only a matter of time. And yet, and yet. While I’ve got any strength left, I’m going to try to rise—and this is what Emily Dickinson deems pitiful.

Three times, ’tis said, a sinking man

Comes up to face the skies,

And then declines forever

To that abhorred abode

How oddly specific she is here, as if this were some sort of rule of thumb. A drowning victim will give it exactly three tries. After the third, so long. Why?

Where hope and he part company,—

For he is grasped of God.

Ah, the drowning person sees God! And so he can now go peacefully under? Not so fast. The last lines:

The Maker’s cordial visage,

However good to see,

Is shunned, we must admit it,

Like an adversity.

God’s “cordial visage”? He’s up there in the heavens being cordial while we’re down here in the cold water, thrashing around? We lurch upward out of the water once, twice, three times. A number of times today, I misread the final word of the poem as adversary, which in a way makes more sense to me than adversity. An adversary you can curse, but an adversity is more impersonal. An adversity is a hump to be overcome. Could God be considered an adversity with respect to the drowning process? I’ve heard it said that after a certain point, drowning becomes an almost ecstatic experience. (How do people know this?) Maybe Dickinson believed it also, and so thought that our attempts to rise were not only pitiful but also unnecessary. Maybe she thought a drowning person should just let it go and not bother at all with a god who won’t lift a finger to help anyway. But as soon as I think this, I disagree with it. God is cordial. God is welcoming. And even so, we fight against him in the last moments we’ve got; we fight tooth and nail, because even the warm face of God is to be shunned if he takes away our wlust to breathe.

Berryman

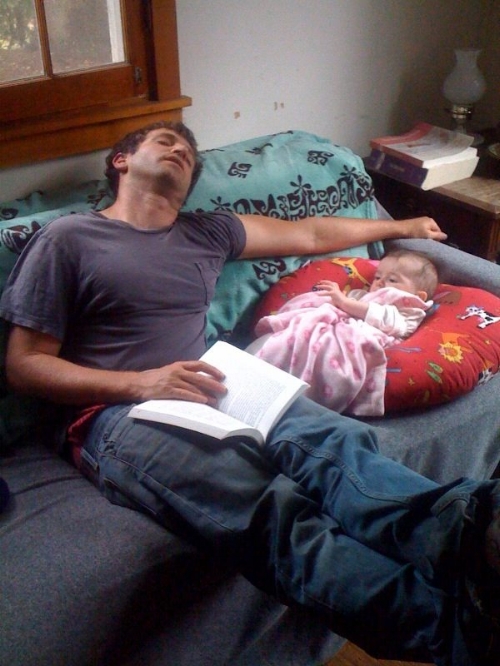

I’m sitting in a park with my six-month-old son. I’m reading the poet Kevin Young’s selection of John Berryman’s greatest hits. The kid’s in his car seat. I forgot the stroller so I have to lug him around in this seat like he’s a little pasha. He’s watching the pigeons. Kid loves pigeons. He turns and gives me the eerie grin that makes him look like a dwarf version of my dead grandfather, Seymour. Would you get a load of these birds?

On the page, Berryman has other questions. I’m not much interested in the pigeons. They aren’t as novel to me as they are to my kid. Six months on earth, pigeons are pretty amazing.

—Are you radioactive, pal? —Pal, radioactive.

—Has you the night sweats & the day sweats, pal?

Yes. Yes. I may well be radioactive, given my effect on certain people. And lately, yes, the day sweats are even worse than the night sweats. My kid’s wearing footie pajamas. And he lovingly watches these flying rats as if they wouldn’t peck his eyes out right now if they could get close enough. That’s how much he knows about pigeons. Berryman, in the last moments of his life, stood on a bridge in Minneapolis and watched the Mississippi rush by beneath him and thought, That’s where I need to be, down there in that January water. He was lonely but I don’t think he felt alone. I think he’d become dull to living. The monotony of the day-to-day. You can hear it in a lot of these poems. I imagine, based on no factual evidence, that he was out there above the river during rush hour. All the people flowing by in their cars, all the packed buses. I wonder if he didn’t just feel crowded out. Literature couldn’t help him then, either. All the talk, all the words.

Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so.

After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns,

we ourselves flash and yearn,

… I conclude now I have no

inner resources, because I am heavy bored.

Peoples bore me,

literature bores me, especially great literature

I know, I know. He’s talking in a persona. I get that. I once took an introduction to poetry class and got a B minus. It is not only inaccurate to conflate the poet with the speaker of a poem, it’s also stupid. All narrators are personas. Even so, I can’t seem to stop myself from imagining him out on the bridge where even Shakespeare wouldn’t have made any difference. His beloved Whitman or his beloved Stephen Crane wouldn’t have, either. On the bridge over the river, Berryman read only the water.

We watch the birds, my son and I. Berryman doesn’t leap. Not yet. He remains. He watches the water. And when he did leave his feet, I imagine, he didn’t leap. Though legend, Kevin Young tells us, says Berryman waved on the way down, I imagine it was more like he just crumpled into the river. Peoples bored him. Literature bored him. Especially great literature. He lied, of course. Literature had always been everything. Until it wasn’t. He lied for a small laugh. He lied for a good line. That was his job. He must have been tired. Tired of lust. Tired of drinking. Tired of despairing. Tired of being scared and lonely. He’d probably been tired for a long time. Anyway, bless him.

Temperley

The hospital’s nondenominational chapel was in the basement next to the cafeteria, which was closed. It must have been after two in the morning. I went in and sat down on one of the folding chairs like I was the first guest at a funeral. There was once a cross in the dead center of the far wall. I could tell because of where the drill holes were. Nobody had spackled them over. I took a book out of my bag to distract myself from how hungry I was. Earlier that day, a specialist had sauntered into my father’s room and asked him his name, though he was holding his chart right in his hand. My father couldn’t talk, only whimper. “Ronald,” I said. “His name is Ronald.”

“Don’t worry, Ronny,” the specialist said. “We’ll have you dancing again in no time.” My father, who never danced. My father, who was always Ronald, never Ron, never Ronny. My father, whose skin was hanging off his body like clothes off a clothes hanger and who’d just shat the bed again. In the chapel, I read the introduction to a translation of a book by an Argentine poet named Héctor Viel Temperley. The translator, Stuart Krimko, writes that after working for years at an ad agency in Buenos Aires, Temperley gave it all up—the job, the car, the apartment, the family—and declared himself a mystic. Temperley wrote that he’d been attacked by God. A handsome god who “looks just like a sailor, a Jewish sailor perhaps, with a strong, square jaw.” I thought of how my father used to keep a sailboat moored in Wilmette Harbor, in Chicago. A Jewish sailor! But my father never sailed anywhere. What he did on that boat was clean it. When he was through cleaning it, he used to say, we’d set sail for Holland, Michigan, where all the pretties still wear wooden shoes. I didn’t care either way. I was fifteen and rageful. The state of Illinois, via a family court judge, had mandated that I spend Saturdays with my father. Wilmette Harbor is small and quaint. My father waited seventeen years for his slip there. He said he suspected it was because he was a Jew. North Shore suburbs like Wilmette had long officially, and later unofficially, excluded Jews. My father never resented it. He said a little healthy American-style anti-Semitism never killed anybody. Toughens you up, he said, like when the Irish kids in Rogers Park used to chase him down and whup him during World War II.

I left the chapel and took the elevator back up to the fifth floor. I watched my father sleep with his eyes open, as if he were too exhausted to shut them, his breathing like a clotted drain. His false teeth had fallen out and were resting on his chest. On the television, some nature show, primates were partying. I sat there in the flickering light, the baboons cawing. Héctor Viel Temperley’s book of poems Hospital Británico is about the time when he was recovering from brain surgery while, in another hospital, twenty blocks away, his mother lay dying. He was in one bed. She was in another. And yet:

Here she kisses my peace, sees her son changed, prepares herself—in Your crying—to start all over again.

My peace? To be honest, I’ve never found very much of it. But here’s something. It isn’t true that my father and I never sailed. We didn’t make it to Holland, Michigan, but we did go out on the lake a few times and once got caught in a freak storm off the coast of Waukegan. In a matter of seconds the sky went from pale to soot and the boat was heeling. If I hadn’t grabbed a cleat, I’d have been in the drink. Then my father turned directly into the wind and the boat stopped moving. It remained suspended, lacking all forward motion, even as the sails and rigging flapped like crazy. If it wasn’t peace, at least for a few moments time itself was arrested. He and I in a howling silence. After we realized we’d survived, my father complimented me on my composure. I told him that I’d had no composure, that I was just confused. I’m still confused. What happened to my father’s teeth? He took such good care of them.

I sat there watching baboons. His eyes are still open when I leave.