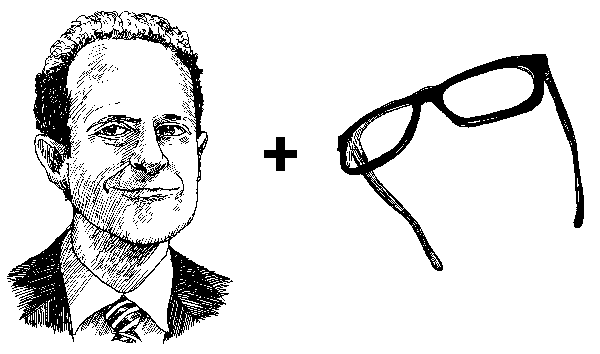

I went to Alain Mikli to buy new glasses, and I came away with glasses by his son Jérémy Tarian. Heir vibe, obedient-patriarchal-descent vibe, suffuses my new frames. From the outside, they seem pure black-blue. Take them off my head, however, and look more closely: they’re pocked, variegated with transparent slivers. Schismatic pockets interrupt the monochrome. I’m wearing interrupted glasses: coitus interruptus. The marbled chunk I’ve stuck on my face—man glasses, Mafia glasses, Ari Onassis glasses—gets peppered and made tingly by striations that take away the blue-black area’s certainty-of-self.

*

Art curators wear glasses like mine. Once I had a brief crush on a curator from Western Europe. I’d seen his picture in Artforum. I thought, He could be in an Alain Resnais movie. (Not Night and Fog.) Decided I needed to “conquer” him. So I sent him a book of mine, intimately inscribed. The inscription mentioned Adorno. This curator wore boxy dark frames and had sexy, thick eyebrows some people would consider unattractive. (My eyebrows are faint, nearly invisible.)

*

The curator with a unibrow never wrote to thank me for sending the Adorno-inscribed book. I no longer have a crush on him. But now my glasses resemble his unibrow, the unibrow that refused to cross the street to say hello or admit blood brotherhood. I can be blood brothers with my glasses instead.

*

One of the most exciting fashion transformations in the last half century has been the passage from nerd to chic: call it the transvaluation of nerd. Nerd—if teletransported Star Trek–style into another decade—becomes alluring, like a boner. Nerd remakes boner and gives us the best of the boner, without its mean edge. (Nerd is a softened identity, like butter left out to temper.) My glasses are boner glasses, the kind of skinny penis that doesn’t frighten a first-timer.

*

My glasses look like Mondrian paintings. Any nerd glasses look like Mondrian paintings, and therefore like the rediscovery of America, as if the United States had converted from imperial entity into carbonation factory, tonic and non-offensive.

*

Maybe my glasses (blue-black rectangles with a perverse undercover striation of nothingness sewn into their hard identity) look like a Monopoly game’s Marvin Gardens and Park Place, or like the beguiling notion of lined-up hotels and houses, Chunky chocolate real-estate tokens.

*

The man glasses I’m wearing contain secret boy identity—boy playing man, boy dressed up as man, boy dressed up as Get Smart’s Barbara Feldon. Turn Barbara Feldon’s personality into rectangles I can buy and wear. Turn Barbara Feldon’s sidekick mentality—her underratedness—into a square entity, an abstraction (Albers’s Homage to the Square) reincarnated as purchasable quiddities on my face.

*

The glasses, two rectangles, have curvy undersides. The outside of the glasses looks rectangular, but when you knock on the door and enter, you discover that they are secretly circular, or contain intimations of ovals. The glasses strive toward the oval (Ovaltine) but never arrive at that milky hereafter.

*

I feel like I’m spitting on someone’s grave by writing enthusiastically about a mere object. Don’t grow too attached to your glasses; someone might steal them. I left a pair on the bench outside a steam room in 1990, and when I emerged from the steam the glasses were gone. I presumed someone had stolen them because he hated me, considered me intellectually or politically inferior, too big for my britches. Those Robert Marc tortoiseshells were my britches: prescription ovals, irreplaceable.

*

And now I feel a wave of nostalgia for another pair of glasses, a pair I won’t describe, because they are too refined, too Eiffel Tower, too El Greco, too wiry, too Philippe Petit, too Jean Cocteau, too Alexander Calder. How can I describe my Cocteau-Calder glasses, changeable as a mobile; skittering as Kandinsky lines shooting jizz-like into space; grounded yet airborne, like John Glenn, handshaked by JFK?

✯

My new glasses are not reincarnations of those Calder-Cocteau astronaut items, whose rectangular oddity I can’t describe. My current glasses—the blue-black rectangles made by Alain Mikli’s son, and therefore incarnating son—are Carlo Ponti trustworthy emblems. But not clodhoppery. Not lame-duck. They are not like the boot of Italy, not downtrodden, not Calabrian; they are Duomo-like, if the Duomo were smashed onto its side and turned into square pellets. Two Duomo sausage patties. Brunelleschi patties.

*

“Don’t get too excited about your glasses—we may need to kill you.” Who is scolding me? Some schoolyard bully? A warden who wants to scapegoat me for disseminating what I once called “fag ideation”? I spread fag ideation around like a Diptyque room spray, to conceal the “head farts” (as Artaud put it) that normative logic imposes on the trippy dreamworld of enlarged thought.

*

When a woman suddenly wears glasses (Maria Callas at her Juilliard master classes), a newfound fox-trot cheerfulness illuminates her face. Charlotte Rampling (especially in her recent films) is the female equivalent of my new glasses. She has a sournois demeanor. Sournois, my new favorite French word, means “sly,” “underhand.” The mouth, expressing slyness, frowns to make a semicircle—a curlicue—that typifies sournois. Charlotte Rampling in Life During Wartime is the living dream of sournoiserie, the state of being underhand. My glasses are sournoiserie practiced like the Goldberg Variations to become a feminine-masculine compromise.

I google-imaged “Jérémy Tarian,” patron saint and creator of my new frames. Turns out he is a glam-nerd doppelgänger dream: big nose, corkscrew-curly hair, thin face, only twenty-three years old, Jewish-looking, but maybe something else beyond Jewish, to spice it up. He might not be Jewish. I want the right to use Jewish as airborne signifier, an adjective as duty-free and pleasure-giving as oval or gleaming or statuesque or ambidextrous. Just a word, a word with a history, an adjective I can throw onto any noun. My glasses are empty, like all good nouns. My glasses aren’t Jewish, but the semiotic ladder they climb (via Jeremy Tarian’s corkscrew curls) leads to Jewishness as grief-free signifier.

*

Also, I want the liberty to use the word penis as a mutating signifier, not as the tried-and-true mother lode of obviousness that wears us all down.

*

Glasses, crystallizations of wish, perch on my big nose—sprained when I played Steal the Bacon in third grade and ran smack into my friend Jimmy Sims. Years later I walked into a glass door in an LA hotel near Japantown. That collision further enlarged and hardened my nose. On its fattened bridge (fatted calf?) sit my Jérémy Tarian glasses, a precious weight, bearing lightly down.

*

I love their sleek matteness, their lack of shine when inappropriate and their sudden efflorescence when appropriate, the alternation of shine/not-shine, a polite counterpoint. The sides don’t shine, but if I wiggle my head the shine emerges and then disappears. A hard-boiled egg slice’s cold flatness resembles the matte sheen of my eyeglass wings, their flight toward the sectioned and the mesa-like, or toward Prague deco furniture—not as stern as the Bauhaus, but lopped-off, like most modernist pleasures. In the spirit of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s phrase “the senile sublime,” or of Willem de Kooning’s late paintings, let’s reconceptualize mental slowness as a form of intelligence; let’s reroute lunacy toward the parallelogram. Imagine what the Jetsons might have chosen for dining-room furniture, if they’d lived in Prague in 1922, and if their cartoon heads hadn’t been filled with Sputnik propaganda, but instead had been programmed with Kafka.