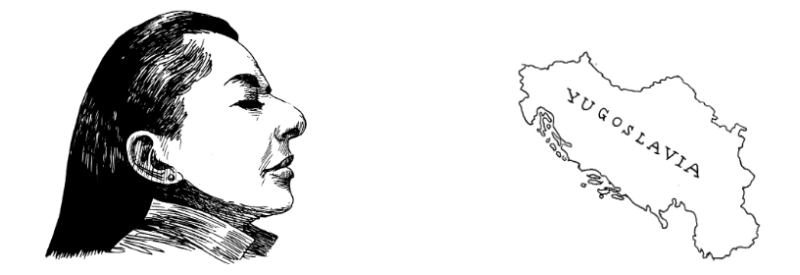

For six hours a day over four consecutive days, in a dank basement in the heat of the summer, Marina Abramovic sat atop a massive pile of raw cow bones, laboriously scrubbing each one clean with a brush and a bucket of soapy water. Projected images of her parents framed her, reflected in copper bowls of water below, and a video showed the artist explaining how trapped rats will kill one another in order to survive. As Abramovic scrubbed, she sang Yugoslav folk tunes, and her white smock became soiled with dirt, blood, and flesh.

Performed at the 1997 Venice Biennale, Balkan Baroque won its top award, the Golden Lion. A public ritual, an act of mourning for the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s, it was a visceral and grotesque affair: the overwhelming stench of the maggot-infested bones that increased over the course of the performance, the enormous presence of death and the need to grieve, and the absence of the violence to which the mass grave referred. In making no specific political statements, no attacks on nor claims to identity, the piece contained aspects of both victim and perpetrator, with no firm boundary between the two.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in