I. THE RING

Wrestling is not a sport, it is a spectacle, and it is no more ignoble to attend a wrestled performance of Suffering than a performance of the sorrows of Arnolphe or Andromaque.

—Roland Barthes, “The World of Wrestling”

Every few years, a New York literary critic remembers how a member of that tribe, Philip Rahv, once sorted American writers into two warring camps: palefaces and redskins. To the paleface camp, Rahv sent Melville, James, Dickinson, and Hawthorne to tend the patrician flames of refinement and ambiguity, and ponder religion and allegory. From the redskin camp, Twain, Whitman, Faulkner, and Hemingway fired more plebian arrows, chewed the fat, and cataloged (or invented) “real” American experience. Rahv feared that the redskins’ twentieth-century dominance impoverished American letters.

Racist, colonialist, and perhaps sexist, Rahv’s theory feels as ill-advised now as it likely did to many in 1939, when he trucked it out. The long list of twentieth-century masterpieces that aren’t composed by white men, not to mention the centuries of music and oral storytelling that Rahv would not have accepted as literature, surely kicks the legs out from under his tired dichotomy.

As a generalization about one over-discussed sector of one country’s field of letters, though, Rahv’s theory is at least diverting, and sometimes insightful. (Henry James and Walt Whitman did indeed annoy the hell out of each other, at least initially.) It’s a cheap, if limited, parlor game—the sort you can self-consciously adapt to other countries’ literary traditions.

The history of letters in Peru, for example, might be playfully understood with a similarly crude dichotomy adopted from Latin American popular culture. Not conquistadors and Incas, the colonial dichotomy Rahv might have reached for, but técnicos and rudos—the battling antagonists of Lucha Libre, the masked free-wrestling phenomenon established in Mexico that has swept the hemisphere.

Mexico’s Lucha Libre yanked out its European roots and became a cultural phenomenon after 1942, when a silver-masked wrestler climbed into the ring for a battle royal. His name was Rodolfo Guzmán Huerta, and he went by “El Santo” (5′ 8″; 215 pounds; born 1917 in Tulancingo, Hidalgo). He dominated until the end, and though he lost the final bout to Ciclón Veloz he impressed the audience with brash and brutal force. Thus began his career as a rudo—what American pro-wrestling calls a heel, or a wrestling villain—but he soon became a good guy—a técnico—and a folk icon. In the 1950s, he starred in his own comic book, and began appearing in movies. With fellow luchadores, El Santo wrestled crime rings, aliens, and pre-Columbian mummies from Mexico City to San Francisco.

As El Santo traveled, so did Lucha Libre, adapting itself to local cultures. On the outskirts of La Paz, Lucha Libre went guerilla: twelve thousand feet above sea level, Bolivian luchadores and cholitas luchadoras—Aymara-speaking women in traditional skirts—launched themselves from the top ropes at wrestlers dressed in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle costumes. If Mexico gilded European wrestling with baroque, colorful masks and angelic aerial maneuvers, Bolivia delivered a version so anti-imperial that it caught the attention of the New York Times and National Geographic magazine: indigenous women driving their high-altitude knees into the solar plexus of Batman, America’s heavyweight corporate fantasy of revenge and surveillance.

Peru’s version of masked wrestling, however, has remained on the cultural outskirts, even as it inhabits halls near downtown Lima, the country’s capital. Less stylized and more popular with working-class audiences, Peruvian wrestling is known as cachascán, derived from the wrestlers of nineteenth-century England whose only rule—“Catch a hold wherever you can”—spoke to disadvantaged grapplers fighting elites the world over. In Peru, those divisions have been far harder to surmount than in Mexico. Whereas the Mexican Revolution led to an earnest attempt to fuse popular and indigenous folk art with the national culture, Peru’s twentieth-century urban elite fled Lima’s center and its swelling working class to retrench with cultural ventures that often took cues from abroad.

Nowhere does that division feel clearer than in Peru’s literary culture. Peru and Mexico vie for having the longest continuous literary tradition in the hemisphere, but, to borrow from Lucha Libre, Peru’s literary tradition is more starkly divided between its técnicos—middle-class or elite golden-glove stylists, often of European descent, writing from inside Lima, punching out arch, clever, clean prose that appeals across borders—and its rudos, the disadvantaged, the urban poor and rural non-elite, trading in oral literature, untranslatable vernacular jokes, and politics without irony. Like El Santo, a rudo writer can become a técnico, but few deign to go the other way.

Yet that division is breaking down. In 2011, a pair of writerly Peruvian grapplers had an idea: what if they could dramatize that struggle between the literary field’s técnicos and its rudos? What if they could give Lucha Libre its most inspired turn yet, and use it to give rudo writers a chance? They dropped an e, added an o, and turned it into Lucha Libro: the Battle of the Books.

II. ROUND 1

True wrestling, wrongly called amateur wrestling, is performed in second-rate halls, where the public spontaneously attunes itself to the spectacular nature of the contest, like the audience at a suburban cinema.

—Roland Barthes

Peru’s Lucha Libro phenomenon began two years ago, when a self-proclaimed rudo writer named Christopher Vásquez rediscovered a play he’d written and packed away ten years before. It was about writers in Mexican wrestling masks fighting for their art. He had written it as comedy, but after years of struggle in Peru’s rarefied literary community, in which he paid to watch his work get published and disappear, it felt like a fun-house version of his own reality.

He showed it to his wife, Angie Silva, who realized that they could turn the looking glass in the other direction. In Lucha Libre, there are winners and losers, and everyone, at the end of the day, whether they’re a técnico or a rudo, gets something from the house. The underdogs often triumph. So what if they could rig Peru’s literary reality with, if not fairness, then at least the contrived justice of pro-wrestling?

Within two months, the literary competition of Lucha Libro was born, a thirty-two-person brawl for a prize that, for an aspiring writer, is almost better than cash: a book contract.

The first rule of Lucha Libro is: fighters must be old enough to drink in the bar where the tournament is held.

“Twenty-three years old!” the announcer calls into the mic, a red bowtie bobbing below his puckish face. “Weighing in at 119 pounds! From the city of Callao! Her favorite author is José B. Adolph! Her name is M. Abraaaaamoviiiic!”

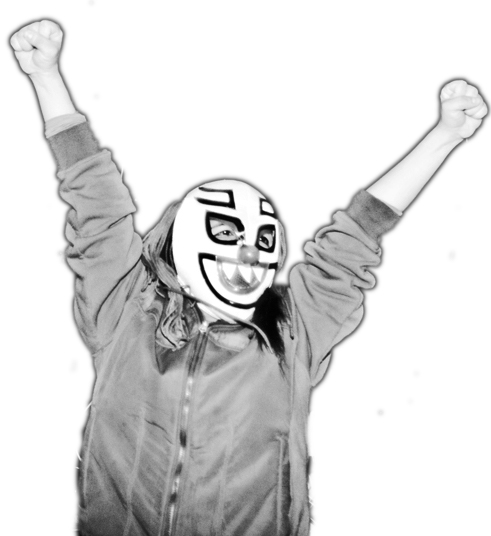

La Noche is a two-story bar and cultural center in Barranco, a bohemian seaside district south of downtown Lima, and it is filled to capacity. The audience is going wild, leaning over the balcony above to get a glimpse of the fighter who takes the stage. If they expected muscles and spandex—or a Serbian performance artist—they’re in for a disappointment: M. Abramovic is short and slight, wearing tight-fitting jeans and a denim jacket. The only hint that this isn’t just a normal Saturday night out for her is the pink Mexican wrestler’s mask she wears.

The second rule of Lucha Libro is: the fighters must be new writers. This means they have never have published before. Not a word.

It may be difficult to make a living as a writer in the U.S., but in Peru it is practically impossible. Book piracy is a huge challenge. There’s a limited market for literary fiction. Funded MFA programs don’t exist. There are no agents or publishing houses that pay advances, and almost everyone has a day job. Most aspiring authors must pay to print their books, often with little editorial guidance. In America, this is considered “vanity publishing.” In Peru, it’s just “publishing.”

Lucha Libro is fighting this state of affairs. This isn’t America’s Literary Death Match, in which book lovers pay to watch famous or emerging writers competitively read their already-polished work. Lucha Libro is for amateur writers without the access or capital to get even as far as self-publishing. Some participants travel over an hour from poorer neighborhoods to compete, and there are writers in the provinces, daylong bus rides away, who want in.

M. Abramovic, for example, lives outside of Lima, and to the attentive and artsy Peruvians in the audience, her stats reflect a wealth of outsider cred. She is from the nearby working-class port city that links Peru to the world, considered dangerous by many of Lima’s wealthier residents. She identifies with the most accomplished science-fiction writer in Peru, a country whose literature is notably genre-averse. And she has named her alter ego after an artist known for intense self-mutilating bodywork—a hint that M. Abramovic will lean into the punches to come.

A beautiful woman in a dress emblazoned with the logo of a Peruvian beer company sashays across the floor with a card reading round 2. M. Abramovic throws her fists into the air, mugging like a champ.

The third rule of Lucha Libro is: no one pays.

In the two years that Lucha Libro has been around, 230 writers have applied to compete, each submitting a short story as an application. From each year’s applicants, the event’s promoters choose the best 32, who then compete in a single-elimination tournament over the course of eight nights. The participants must come up with pseudonyms and stage personas, and Vásquez and Silva provide the masks, ordered from a workshop in Mexico. Their audience also pays nothing; the whole tab is picked up by the event’s media sponsors.

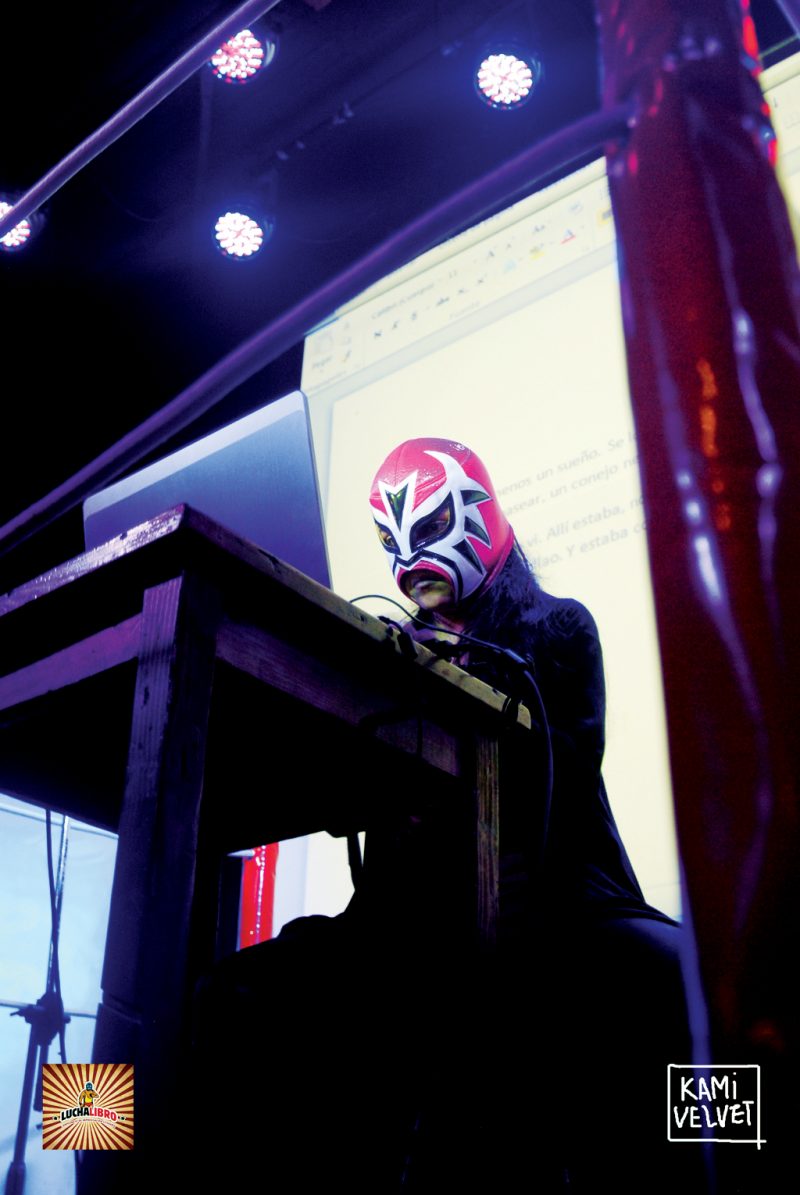

Glossy, ad-quality images of three objects appear on the screen behind M. Abramovic: a pair of jeans, a math textbook, and a hard drive. She briefly gazes at each, then steps into a white-roped ring, five feet square. She sits down at a tiny desk, empty save for a sturdy black laptop PC.

The fourth rule of Lucha Libro is: the fighter must be able to write.

The sports timer begins its countdown. M. Abramovic has five minutes to craft a short story incorporating each of the given objects. Then a second writer will get a chance. Three judges—established writers and editors from Lima’s literary establishment—will choose between the two stories, offering critiques and moving the winner on to the next round.

If M. Abramovic loses, she will have to remove her mask, revealing her identity, just as in Lucha Libre. But if she wins, and keeps winning, and makes it through to the final night, she’ll leave her mask on, and eventually receive a contract to publish her first book with the editorial house Mesa Redonda.

M. Abramovic lays her fingers on the keys.

I would only strip myself of my excess, she writes. I was already there. There was no turning back.

The crowd falls silent, hanging on the words that spill across the screen above her. Her typos leak red slashes, like a fighter bleeding on the mat.

III. THE GREATS

The public is completely uninterested in knowing whether the contest is rigged or not, and rightly so; it abandons itself to the primary virtue of the spectacle, which is to abolish all motives and all consequences: what matters is not what it thinks but what it sees.

—Roland Barthes

Rahv’s paleface/redskin model sought to explain a division that’s more than a century old, and its usefulness has long ago worn out. Peru’s rudo/técnico divide, however—if we entertain the idea—is one that goes back nearly half a millennium.

Peru’s longer time scales, both literary and historical, are a source of great pride to its writers, even if they unnerve Americans. (Herman Melville, who spent a lot of time in Lima before becoming an alleged paleface, bemoaned the “white veil” of clouds that cloaked Peru’s coast, keeping her ruins from “the cheerful greenness of complete decay.”) Peru’s long, dry coast—as if thousands of miles of sand and scrub divided Seattle and San

Diego—preserves the oldest temples and urban centers in the Americas, dating to 3000 BCE, and the aqueducts and terraces that made the region the New World’s greatest agricultural laboratory. When the Spanish reached Peru, in 1532, they found that the Incas’ privileged record-keepers shared pre-Columbian stories and knowledge through songs and stringed devices called quipus. The Spanish tried to root those traditions out, but they listened to those indigenous lords first.

One of the best sources for Incan history, and one of the first examples of a técnico, was Garcilaso de la Vega, the warrior-poet son of a Spanish conquistador and an Incan noblewoman. He was born in Cusco, the Inca capital, and died in Córdoba, Spain. His Comentarios Reales de los Incas honored his matrilineal history—the start of a long line of Peruvian técnico literature composed either in Europe or in dialogue with its traditions, in an elegant, poetic style nonetheless filled with nostalgia for the Incan past. He published with the blessing of the crown.

Others, with the wrong set of parents, were less lucky. Garcilaso died in 1616, a year after the most famous rudo of his contemporaries, Guaman Poma de Ayala, mailed off his own illustrated masterpiece to the King of Spain. To credit El Primer Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno (The First New Chronicle and Good Government) as one of the Americas’ first graphic novels is trivial praise. Think of it instead as the Peruvian Popol Vuh, Pilgrim’s Progress, A People’s History of the United States, and Maus rolled into one, with no editor in sight. Unlike Garcilaso, Guaman Poma was a minor Incan lord who never left Peru. His 1,189-page manuscript recounted the Spaniards’ abuse of indigenous subjects and argued that he and his son were the Inca empire’s true heirs. It would be the very definition of a jeremiad if it weren’t also ineffably beautiful, detailing Andean culture, history, and knowledge, tinged with Guaman Poma’s Christian conversion and millenarian vision of the future. It’s been a growing scholarly obsession since its rediscovery, in early twentieth-century Denmark, but in 1616 it disappeared in the king’s slush pile.

Peruvian rudo writers could expect worse than editorial silence. It was fine for priests at the oldest continuously operating university in the Americas (the National University of San Marcos, signed into existence in 1551) to study Andean legends, layering them with Catholic cosmography and natural history. But when eighteenth-century indigenous revolutionaries folded Incan traditions into their uprisings, Peru’s nervous whites stripped indigenous lords of their rights and began bowdlerizing the history. Through Peruvian independence in the 1820s and most of the nineteenth century, Peru’s técnicos celebrated the Incas as peaceable model citizens, but contemporary natives were infantilized or considered savages. In response, rudos in fin-de-siècle Peru helped birth one of Latin America’s most important literary movements, indigenismo—a mix of social criticism and realist fiction that damned Europeans for oppressing Indians. Practitioners often ended up exiled, shot, or at the bottom of a literary pile-on, like Cusco’s Clorinda Matto de Turner, whose pro-indigenous, anti-clerical Birds Without a Nest hurried her flight to Argentina, where she died, in 1909.

And then there’s José María Arguedas, arguably the most important Peruvian writer of the twentieth century, and virtually unknown in North America. Arguedas is easily classifiable as a rudo, but without him there’s no Mario Vargas Llosa, the consummate técnico (and Peruvian letters’ famed Nobel Prize–winner). Born in 1911, Arguedas was raised speaking Quechua, and wrote books that churned in the humid space between fiction and anthropology. His beautiful, complex, and thoroughly uncommercial novels, filled with half-Quechua, half-Spanish dialogue, asked whether the depth of oppressed Andean life and legend could survive alongside creole Peru. He made little money, but inspired many, who, like Vargas Llosa, then slingshotted out of Arguedas’s orbit, firing backward as they went. In the 1960s, he was marginalized as a naive folklorist by an international literary community enchanted by the more-translatable

Peruvian representatives of Latin America’s literary boom. Heartbroken by the industrialization that he feared would destroy the countryside, Arguedas killed himself before completing his final book, a messy, masterful collage of fiction, suicidal diary entries, and pre-Columbian legend, called El zorro de arriba y el zorro de abajo (The Fox from Up Above and the Fox from Down Below).

Arguedas died at the start of twelve years of military government. When it was over, the country was in economic crisis, and a rising cycle of violence between state forces and revolutionaries killed over sixty-nine thousand in the period between 1980 and 2000. The dead were mostly indigenous, mostly from the countryside, caught between the hammer and sickle of the Maoist rebel group Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and the anvil of the Peruvian military.

It was a hard era, but Vargas Llosa, a técnico sin paralelo, remained a cultural and political force in part by drifting to the right. The younger Vargas Llosa, author of left-leaning celebrations of individual resistance against the military, like La ciudad y los perros (The Time of the Hero), gave way to a more jaded writer, one who described a lost indigenous countryside and cast Arguedas as a naive (and dangerous) utopian. In 1990, Vargas Llosa ran for president on a conservative platform: imagine William Faulkner, one of Vargas Llosa’s touchstones, living long enough to run against Nixon as a Southern Libertarian in ’68, and you begin to get an idea of this campaign’s strangeness. Vargas Llosa lost to the corrupt and oppressive Alberto Fujimori, sold his mansion in Barranco on the condition that the buyer tear it down, and moved to Spain.

IV. ROUND 2

…Out of five wrestling matches, only about one is fair. One must realize… that ‘fairness’ here is a role or a genre, as in the theater: the rules do not at all constitute a real constraint; they are the conventional appearance of fairness.

—Roland Barthes

It’s no accident that Peru’s literary rudo/técnico hall of fame is dominated by men (of mostly European descent, at that). From the colonial era through the mid-twentieth century, Peruvian women exercised great power in the private sphere—and, interestingly, in finance—but they were repressed in public, allowed little room to play and critique their culture through writing. Beginning with Blanca Varela, in the 1950s, poets, critics, and journalists—like Rocío Silva Santisteban, Doris Moromisato, and Mariela Dreyfus—have carved out space for women in Peruvian letters. Novels and short fiction overwhelmingly remain a boys’ club in Peru, however, and book-release parties are attended by a familiar cast of horn-rimmed hombres.

Which is one of the most thrilling aspects of Lucha Libro: it’s not just that its audience is more diverse and enthusiastic (and there is real joy to be found in hearing a Lucha Libro crowd member, after a contestant accidentally deletes his entire story with only thirty seconds remaining on the clock, urgently shouting: “Control-Z! Control-Z!”). More exciting is the fact that almost half the participants are female, and, what’s more, they are writing to win.

I still remember that night. That goddamn night.

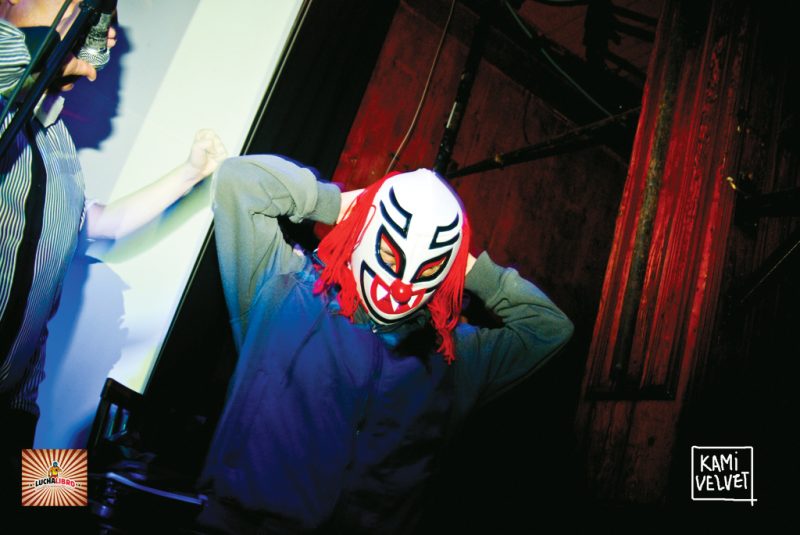

Deceo—or “Dezire”—is wearing sunglasses over her black-and-white mask. Its Raggedy Ann coiffure of red yarn tumbles over her tweed jacket. The screen had flashed images of a sweater, a toy top, and a pair of sunglasses.

“A drink, sir?”

“No, just a bottle of water for now.”

Dezire is two minutes into a story of a self-satisfied man expecting his lover to walk into his bar. Nothing could go wrong, she writes. Nothing.

A twenty-three-year-old architecture student, Dezire is from San Juan de Miraflores, a working-class neighborhood far from Lima’s center. Her parents left the southern Andean countryside for the coast in the 1980s, seeking better opportunities and an escape from Sendero Luminoso’s violence. Her favorite writer is Alfredo Bryce Echenique, whose accessible and sharply observed fictions skewered Lima’s elite, before he was accused of plagiarism in his nonfiction. Although this is her first time writing short fiction, she’s killing it, and the crowd is clearly on her side. The beautiful lover has asked Dezire’s narrator to murder her husband; the narrator has done the job and is waiting for her to make their getaway. But time ticks by and it’s clear that she’s not coming.

That damn liar. I imagined her laughing at me, her new lover kissing the tattoo on her back.

As Dezire nears the end, it becomes clear that she plotted her story ahead of time, and is weaving her prompts in as details. Some writers use the prompts for genuine inspiration, as plot points around which they improvise, but both approaches are allowed. Dezire’s approach is better suited to planned twists, like the one she now drops.

They will find her, the narrator growls. I left her fingerprints at the scene of the crime.

It’s nothing fancy, but it works, winning a murmur of approval from the crowd. Finished, with time to spare, Dezire inspects her construction, sweeps out the typos, and hangs a title honoring the venue: “La Noche.” The clock strikes zero and she recites her story into the microphone. The crowd cheers.

A young man in a black mask with Batman ears composes his own, more explicitly violent—and less successful—noir using the same prompts. When he’s finished, he and Dezire stand side by side, waiting for the literary judges to choose a winner. The editors take the mic and quickly critique the stories. They name Dezire the winner. She pumps her fists, jumps up and down, and the crowd goes wild. Like a good luchador, her male opponent removes his bat-mask and smiles sheepishly. He’s young; he’ll write again. Dezire, meanwhile, is one step closer to a book contract. She goes home to practice.

V. ROUND 3

But what wrestling is above all meant to portray is a purely moral concept: that of justice. The idea of ‘paying’ is essential to wrestling, and the crowd’s ‘Give it to him’ means above all else ‘Make him pay.’ This is therefore, needless to say, an immanent justice.

—Roland Barthes

It’s five weeks into Lucha Libro 2012’s eight-week cycle, and M. Abramovic, the pink-masked fighter who won her first match with a Tarantino-esque story of plastic surgery gone wrong, is pushing the limits of one of the competition’s unspoken, self-imposed rules: there’s no place for politics in fiction.

If the police had found me, she types, they’d give me ten years in prison and the life of a housewife, pushing a supermarket cart.

Considering how much Peru has been through over the last thirty years, one would think that a competition that drops its young citizens into a public free-writing spectacle might produce the sort of sharp societal commentary that has flourished in Peru since Guaman Poma—and that remains a major theme of writers just one generation older. But the written performances of Lucha Libro rarely, if ever, hint at truth commissions, terrorist attacks, or class conflict.

I still remember how it happened, Abramovic continues. I was coming back from my job at the magazine, that piece-of-shit job I’d accepted because we needed to live. I couldn’t give her luxury, but I had to take care of her. She was the artist of the family.

It might be optimism. Economically, Peru is roaring along, and its literary scene is reaping the benefits. New literary journals and novels are being published regularly, featuring playful yet serious work like Jerónimo Pimentel’s La ciudad más triste (The Saddest City), which reimagines the Lima that so depressed Melville. Lima is also home to Etiqueta Negra, one of the hemisphere’s most respected magazines for narrative nonfiction, and the tabloid El Trome, the newspaper with the highest circulation in all of Latin America. Like Lucha Libre before it, Peru’s literary surge is spreading. Christopher and Angie have been asked to help organize Lucha Libro Brazil, and—in a wonderful twist of looking-glass logic—Lucha Libro Mexico.

Yet back in the Andes, national anxieties lurk just below the surface. Despite Peru’s economic growth, millions in the countryside lack access to the consumption- and construction-driven boom. The government has figured out how to make money, but not how to spend it, leaving social programs underfunded and struggling. Women remain disadvantaged by wages, sexism, and violence, and social conflict remains a problem: at least fifteen people have died in police responses to protests since Peru’s current president, Ollanta Humala, took office, in July 2011. There’s still basic disagreement over the political violence that exploded thirty years earlier: was it all the fault of terrorists, or a function of an exclusionary society? Shining Path’s imprisoned leader, Abimael Guzmán, and ex-president Alberto Fujimori, convicted of embezzlement, bribery, and human rights violations in 2009, both enjoy the support of dueling amnesty movements trying to spring them from jail.

What was a person doing cutting her veins in the doorway of her own house? I threw her in the car, put it in first and we fly to the hospital.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising, then, that Lucha Libro’s participants check their politics at the door. For her second story, Dezire wrote about yet another man taking revenge upon his ex-lover. She revealed afterward that the story was inspired by a relationship between a Shining Path terrorist and a journalist, but she had stripped out the identifying details. “I didn’t want to turn anyone off,” she explained.

“I didn’t want to get myself into anything political.”

Which is in itself a political decision, of course. This was thrilling escapist fiction, but also the work of a young generation of writers who had grown up in an era of violence that was both random and ideologically motivated; who had learned to distrust strong political affiliations as well as the state; who were now being bombarded by an increasingly violent global pop culture. As the judge and writer Enrique Planas observed, part of Lucha Libro’s success lies in the way it turns literature itself into a spectacle, into a reality-TV show whose format mines deep social anxieties.

The deepest anxiety Lucha Libro’s stories expresses seems to be the looming threat of sudden, catastrophic violence in middle-class life. Beatings, murders, and acts of revenge against criminals are drafted and redrafted in the ring. The winner from 2011, Maladjusted (real name: Francisco Hermoza; age: twenty-nine; favorite author: H. P. Lovecraft) upstaged the técnicos with entertaining stories about serial killers, cannibal families, and beaten-down boxers. In 2012, however, this didn’t seem like only an issue of genre, or “boys being boys,” as some observers suggested, but of something more endemic, a trend as likely to be explored among the winning female writers as the men. Male and female contestants alike write about romantic relationships and nostalgia, but they are quickly eliminated from the competition.

The hermetic republic of Peru is false. But I can’t denounce it; everyone has already changed.

M. Abramovic checks her spelling, cleans up her punctuation, and adds a title: “Fahrenheit 2012.” A little on-the-nose, but she wins and goes with Dezire and an eighteen-year-old female writer to the quarterfinals.

Which is where they lose, one after the other. Lucha Libro’s final four will count no women among their number. Dezire removes her clown mask to reveal Diana Castro Ortega, twenty-three. M. Abramovic removes her mask to reveal Lucía Carranza Sotomayor, also twenty-three. Both are disappointed, but neither will give up. Diana goes home to start her first novel, about terrorism and the Andes. Lucía salutes the balcony with a mask-wrapped fist, then sits down with her family. They’ve traveled an hour to watch her compete. She cries, composes herself, and orders a beer. She has her defenses in place, remains hopeful. She is a performance artist by night, plotting weekend interventions in Peruvian culture, and by day she works for the government agency tasked with awarding reparations to victims of the twenty-year conflict between Shining Path and the government. The hardest part of the job, she says, is processing rapes that were never documented. “There’s no more proof than the interview,” Lucía explains. “There’s only belief in a person and their story.”

VI. THE MAIN EVENT

Some fights, among the most successful kind, are crowned by a final charivari, a sort of unrestrained fantasia where the rules, the laws of the genre, the referee’s censuring and the limits of the ring are abolished, swept away by a triumphant disorder which overflows into the hall and carries off pell-mell wrestlers, seconds, referee and spectators.

—Roland Barthes

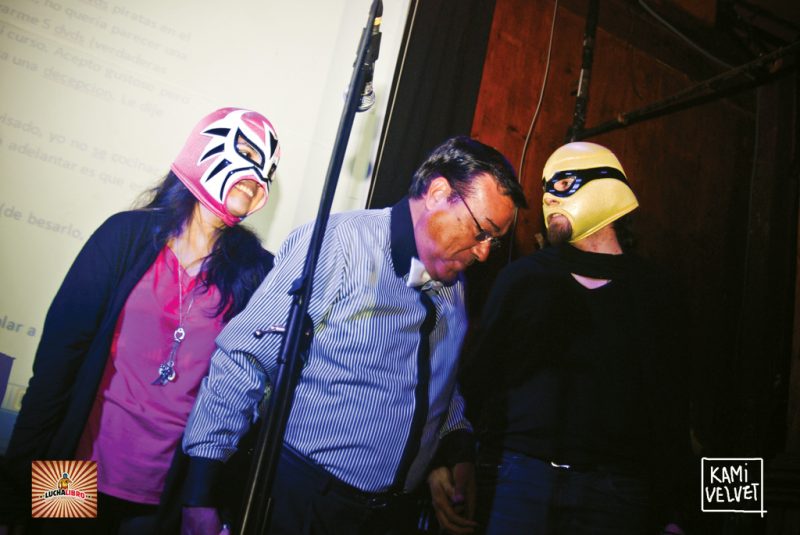

It is the final night of Lucha Libro 2012, and Christopher Vásquez, the event’s co-promoter, is warming up the crowd with Peruvian jungle grooves and vintage footage of El Santo wrestling matches. In the cave below the stage, covered with graffiti left behind by local rock bands, the writer who beat M. Abramovic begins to stretch. His name is Ruido Blanco—White Noise—and though he says that waiting in the cave makes him feel like a gladiator, he seems a little nervous. White Noise is twenty-six, tall and fair-skinned, with a goatee poking out the front of his mask and a ponytail tumbling out the back. He lives in Santiago de Surco, one of Lima’s tonier neighborhoods. He says his favorite writer is José Watanabe, whose poems memorialize a rural childhood in sparse, ephemeral verse. White Noise is one of the few contestants to genuinely improvise his compositions in the ring, circling back later to enrich metaphors rather than construct plot. He has been practicing, running himself through five-minute writing drills. He says he’s been eating healthy.

White Noise has an advantage beyond vegetables and grains, though. Unlike many of his competitors, he has a writing mentor, a digital publishing venture, and—advantage of advantages—he has already published his first book: a sixty-page collection of poems with Mesa Redonda. White Noise says that he asked Lucha Libro’s organizers before the competition began if it was all right that he had published before; Christopher and Angie say that they learned of the book only mid-tournament, admitting that they had not made clear the “rule” that contestants lack publishing experience. They decided that it mattered less whether a writer has published a book before than if he has published a book of stories. But they also decided that they would be more strict for Lucha Libro 2013.

Either way, when White Noise takes the stage, he shows no sign of having already attained the golden ring that his competitors strive for. They see only a man in a black cape, eyeing them with feigned suspicion. As he settles into his seat in the ring, the prompts flash up on the screen: a kerosene canister, a walker, and an IV bag. White Noise makes another of Lucha Libro’s few political jags, plotting out an assassination of a bedridden military patient who may or may not be Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez. The story handily defeats an ultraviolent fantasy of revenge against a serial killer.

To take the final match, and the championship, he has to defeat Bucephalus, the favored writer of the evening, if not the entire series. It’s not hard to see why the crowd likes him so much. Bucephalus—named for Alexander the Great’s horse, or Baron Münchhausen’s—is from rough-and-tumble but recovering downtown Lima. In person, he waxes poetic about the importance of truly “Peruvian” writers, but his own subject matter is fairly universal—optimistic stories of magic, self-discovery, and love. He cites G. K. Chesterton as his favorite author—a throwback to the early twentieth century, perhaps, when the palabra inglesa (“English word”) represented everything forthright, honest, and true. Bucephalus seems to be another planner, sliding the prompts into a story he’s conceived in advance.

When he gets onstage, he mugs for the crowd, his glasses perched outside his smiling red and gold mask. “Bucephalus!” a group of women in the balcony shouts in unison. As he composes a surrealistic, dream-within-a-dream love story, a few couples actually shuffle-dance to the rhythm of his typing.

When the judges give the championship and the book contract to White Noise instead, Bucephalus’s eyes glaze over. Partisans catcall the decision, but the celebrity judge, the white-haired, leather-jacketed Oswaldo Reynoso, suffers no grousing. Reynoso was the first writer to bring homosexuality openly into Peruvian literature, incorporating the rough language of downtown Lima into his writing. He is one of the Peruvian members of the 1960s boom who don’t spend most of the year abroad. The eighty-one-year-old praises White Noise’s use of syntaxis, and the “contrapuntal structure” of this quiet, sardonic story about a man cooking pumpkin while listening to a cardinal’s sermon on the radio.

“Literature is art,” Reynoso tells the crowd, pointing a finger into the air.

But art is defined by privilege, taste, and access, centuries accrued. It’s not that White Noise isn’t a good writer or a sensitive person, or that he doesn’t deserve a contract with Mesa Redonda or the belt that the ref is trying to snap around his waist (which he’s awkwardly resisting). It’s that White Noise is already a técnico, with mentorship and editorial support. It’s hard not to feel that Lucha Libro created an exciting new path to publishing, but in 2012 forgot to screen out the advantages that rig the game outside of the ring, leaving the fight inside lopsided.

Then again, this is what spectators love about pro-wrestling: the lack of fairness that makes that final, delayed turn of fate so cathartic. Wrestling makes clear the division between hero and villain; it teaches loyalty and indignation. “In the ring, and even in the depths of their voluntary ignominy,” Barthes wrote, “wrestlers remain gods because they are, for a few moments, the key which opens Nature, the pure gesture which separates Good from Evil, and unveils the form of a Justice which is at last intelligible.” Thrown back on the straining ropes of Peruvian letters, Lucha Libro shows the rudos what they still have to fight for: the denied victory for which they need to get in the ring, and write.