It’s sometimes easy to forget that our technologically complex world wasn’t created out of whole cloth. Or that it wasn’t always here. Without an awareness of the past, “the sense of time falls in upon itself,” writes Lewis Lapham, “collapsing like an accordion into the evangelical present.”

“Vintage Tech,” a new Believer column by B. Alexandra Szerlip, will examine some of the under-the-radar stories, personalities and techniques that inform our 21st century lives.

The odyssey, at times hilarious, of the ballpoint pen is a window into entrepreneurship and America’s consumer mentality at the start of the postwar (post WWII) period.

The first “ball tip” pen patent was filed back in 1888, the invention of Massachusetts leather tanner John Loud, who needed to mark hides, but it was never commercially exploited. Fifty years later, Hungarian journalist László Jozsef Biro—frustrated at always having to fill up fountain pens and clean up smudges—noticed that newspaper ink dried almost immediately, leaving the paper relatively smudge-free. But newsprint ink was too thick to flow through regular pen nibs (which often tore up the newsprint); he and his chemist brother, Georg, set to work making models. Their eureka moment came, the story goes, while watching boys playing street marbles; one marble, having rolled through a puddle, left a line behind it. The brothers devised a point fitted with a tiny ball bearing that, fed by a fine-coiled tube in the barrel, rolled (rather than poured) ink onto the page.

When WWII broke out, a few years later, the brothers fled to Argentina, found some investors (including Argentina’s president, Augustine Justo), filed a second patent, and opened a factory. The initial 20,000 run of the Biro brothers’ Strato-pen—advertised to work for six months without refilling—was quickly gobbled up. That it also functioned at high altitudes without leaking (more or less) caught the attention of the British Royal Air Force, who bought the licensing rights for the war effort. By the time the U.S. Air Force got wind of it, various stateside companies were vying for the rights.

Enter Milton Reinsberg, a Minnesota-bred high school dropout, entrepreneur and inveterate risk-taker who, at 53, had already earned and lost three fortunes (and changed his name to Reynolds) before the fateful day he spotted Biro’s pens in a Buenos Aires shop.

After a decade and a half of war rationing and Depression-induced deprivations, the American populace was hungry for novelties. Thinking ahead to the first post-war Christmas season Reynolds—who knew nothing about the pen business—quickly devised a way to get around the Biro patent. Working with an engineer, he re-formulated Biro’s ink, renaming it “SatinFlo,” and reconfigured the “feed” system from one based on capillary action to one that relied on gravity (the law of gravity being un-patentable)—thus also circumventing Eversharp and Eberhard Faber’s exclusive U.S. rights, rights acquired a mere few weeks before Reynolds happened upon the Buenos Aires shop.

Armed with a single sample pen, he convinced Gimbels Department Store in Manhattan to place an order for 50,000. (In 1901, its finger already on the zeitgeist, Gimbels’ Manhattan store installed the very first stair escalator, which had debuted at the Paris Exposition the year before.) With one pen, no factory, and a twenty-three-day lead time, Milton tracked down a machine parts manufacturer who specialized in watch movements, purchased crates of war-surplus aluminum (for the barrels and caps) and bottles of 1-millimeter stainless-steel, war-surplus ball bearings, hired 300 workers, and began production. His wife and daughter pitched in.

Every ball bearing was inserted by hand. The barrel tip (brass) was crimped into a socket with one-ten-thousandth-of-an-inch clearance, then the “SatinFlo” dye was forced though the tiny opening.

The first day of production, they managed to assemble seventy pens.

Gimbels took out a full-page ad in The New York Times, announcing the imminent arrival of a “fantastic, atomic-era marvel,” aka “Buck Rogers’ baby,,” that wrote for two years without refilling, whether 20,000 feet in the air or on “the remotest ice floe in the Aleutians.” Two days later, on October 29, 1945—less than three months after V-J Day—Milton’s International ballpoint went on sale with a hefty price tag of $12.50, the present-day equivalent of about $167.

The packaging was minimal, elegant: a clear, vertical, plastic tube within which the pen posed like a rocket about to launch.

Some 5,000 shoppers snatched up $125,000 worth on the first day alone; dozens of police were dispatched to quell the frenzy. Emergency counters were set up and fresh supplies hastily brought in. “We took over Umbrellas, we knocked out Clocks, and we went into Silver,” a Gimbels employee recalled years later. Gimbels’ owner, Fred Gimbel, insisted that all sales receipts be written with Reynolds’s masterpiece. By week’s end, 30,000 pens, plus 12,000 via mail order, had sold. Buyers from across the country began flying in to meet with Reynolds, whose pens were showing up everywhere from barbershops and gas stations to hot dog stands. By early December, Reynolds had a million-pen order backlog.

That the pens tended to leak or skip, that the ink sometimes fermented or, thanks to the proximity of body heat when carried in a breast pocket, rose up the barrel and formed a bubble, blowing the ball bearings right out of the pen (perhaps why Time Magazine referred to Reynolds as “the Old Faithful of ballpointpenism”) did little to stem the tide. Reynolds began giving cash prizes to druggists who had the best window displays of his product. By the end of November, he’d accrued a net profit, after taxes, of $541,000, more than $6.5 million today. (Each $12.50 pen cost 80 cents to make.) Within three months of the initial launch, 5.3 million Internationals had sold.

While putting the finishing touches on his gravity-fed wonder, Reynolds had stumbled onto the fact that it wrote, without blurring, on a soggy cocktail napkin. A tag line was born: “It Writes Under Water!” (He hired famed swimmer Esther Williams to prove it.) Who, other than mermaids or Jacques Cousteau, would need that? But Milton guessed it would get people talking.

Three years later, in the Three Stooges’ film “Heavenly Daze,” Larry will ask why anyone would want a pen that writes under whipped cream. They might be in a desert, brother Moe suggests, where there’s no water to write under.

Unable to create enough inventory to meet the demand, he began issuing gift certificates; $100,000 worth sold the first day. Meanwhile, shipments began disappearing en route. Some $750,000 worth of pens and pen parts were smuggled, piecemeal, out of the factory, including 200 complimentary pens custom-stamped “I Swiped This From Milton Reynolds.” (They turned up for sale in Chicago.) Milton expected the demand to drop after Christmas, It didn’t. Some orders were for as many as 100,000. By February 1946, Reynolds had 800 employees, who were cranking out 30,000 pens a day, and his after-tax profits had reached $1,558,607 (more than $19.5 million today).

“Take a look at the Constitution,” competitor Waterman sneered. You wouldn’t get that variety of signatures with a ballpoint! Eversharp stepped up to the plate, staging “torture test” demonstrations that anticipated the Fisher Space Pen, still twenty-two years in the future—pounding a pen through a block of wood with a hammer, sealing it in a vacuum jar (the equivalent of 15,000-foot altitude), tossing it into a vat of dry ice (good for trips to Antarctica). Reynolds rallied with a retractable-point (cap-less) pen, The 400, complete with interchangeable top—one for men, one for women. “The most unusual writing instrument of civilized times!” Gimbels decried. “No cap to fumble with, drop or lose! … The new Reynolds is, is, is!” The day The 400 was released, Milton threw a massive cocktail party at the Waldorf. Little girls in leotards and ballet shoes posed with the new 400s beneath a twelve-foot replica.

Samples were handed out to senators, ambassadors, film stars, hole-in-one golfers and master bowlers. He sent the President 200 inscribed “I swiped this from Harry S. Truman.” Newspapers that ran stories mentioning The 400, and comedians who worked them into jokes, were rewarded, one pen for every nod. By the summer of 1946, the pens were selling in thirty-seven countries, as far afield as Pitcairn Island where the locals, the cash-poor descendants of Captain Bligh’s mutineers, allegedly paid for their consignment with handwoven baskets. Reports had them selling in Hong Kong for as much as $75 apiece.

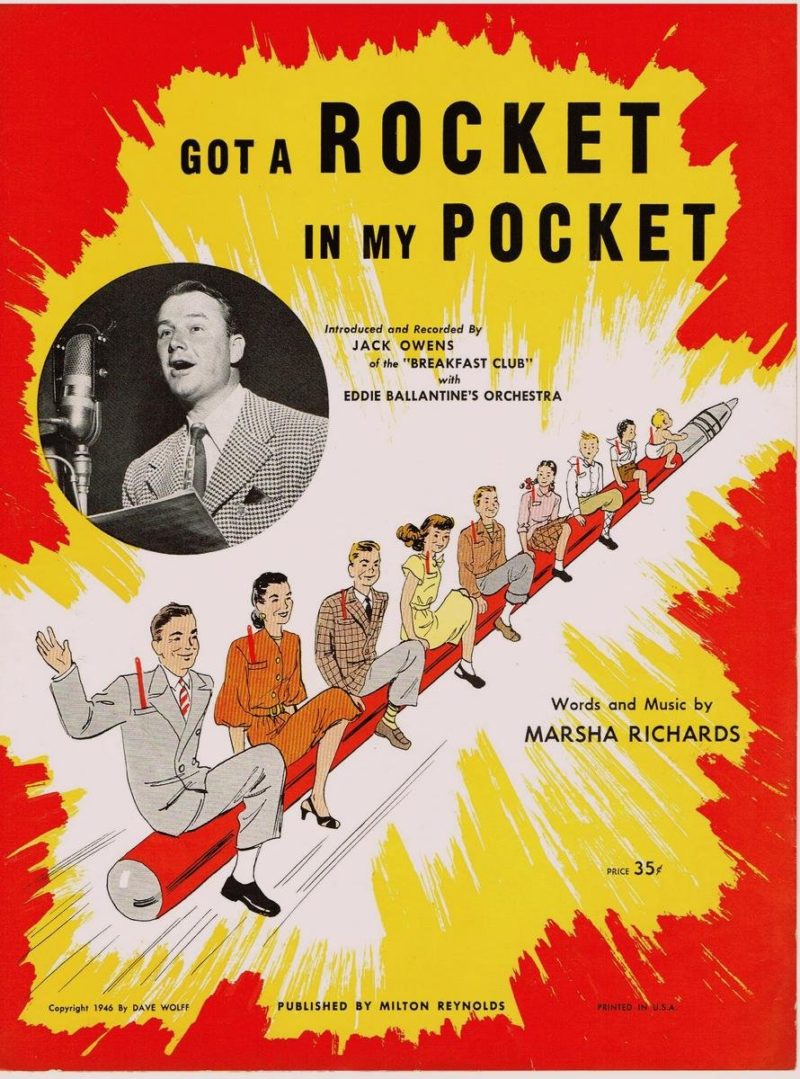

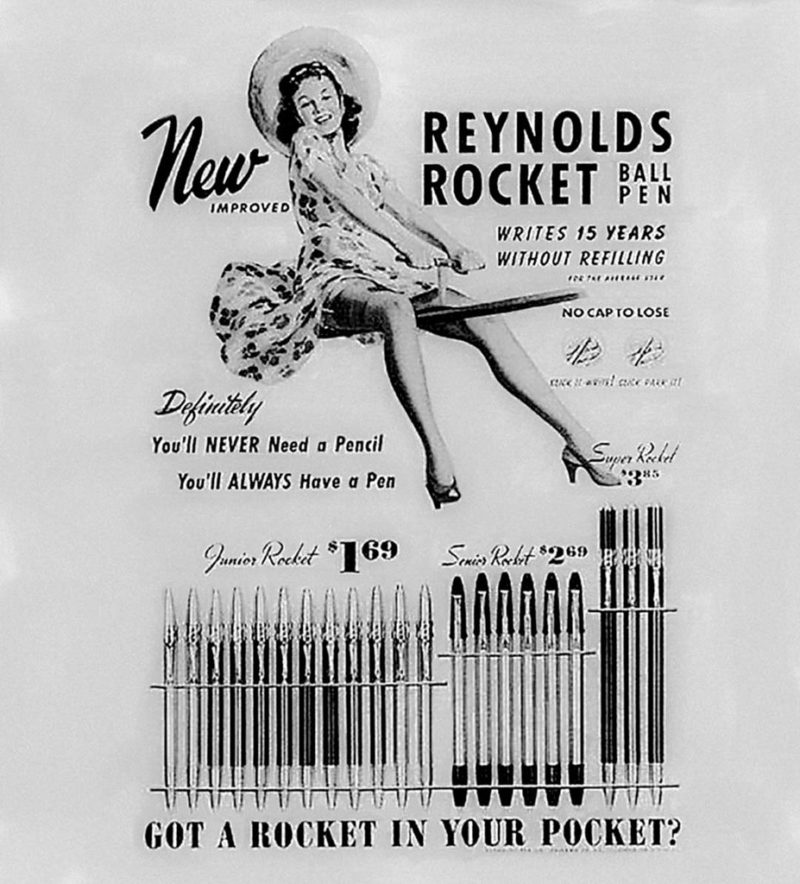

But by the following spring, with the competition growing (some 100 U.S. manufacturers were vying for a piece of the pie), Macy’s and Gimbels began price cutting, selling Reynold’s pens for as little as $1. At first, Milton threatened to sue under the Fair Trade Act, but with orders pouring in from across the country, he decided, instead, to just keep cranking them out at a rate of 80,000 a day. Reynolds met the challenge with the Reynolds Rocket—available in stratospheric blue, atomic red, radar green, jet black, chute silver, and cosmic gold, good for fifteen years or thirty-two miles nonstop (whichever came first)—followed by the modestly priced Rocket Threesome—the Rocket, the Rockette, and the Stubby Rocket. ”We have acres of diamonds right here in our back yard,” noted a Reynolds executive. Added Reynolds: “It’s simply crazy.”

Magazine ads featuring a young girl straddling an enormous pen between her legs asked the provocative question: “Got a rocket in your pocket?”

Milton used some of his personal profits to buy a 17th century chateau, complete with moats, near Versailles.

Still, it was time for a new angle.

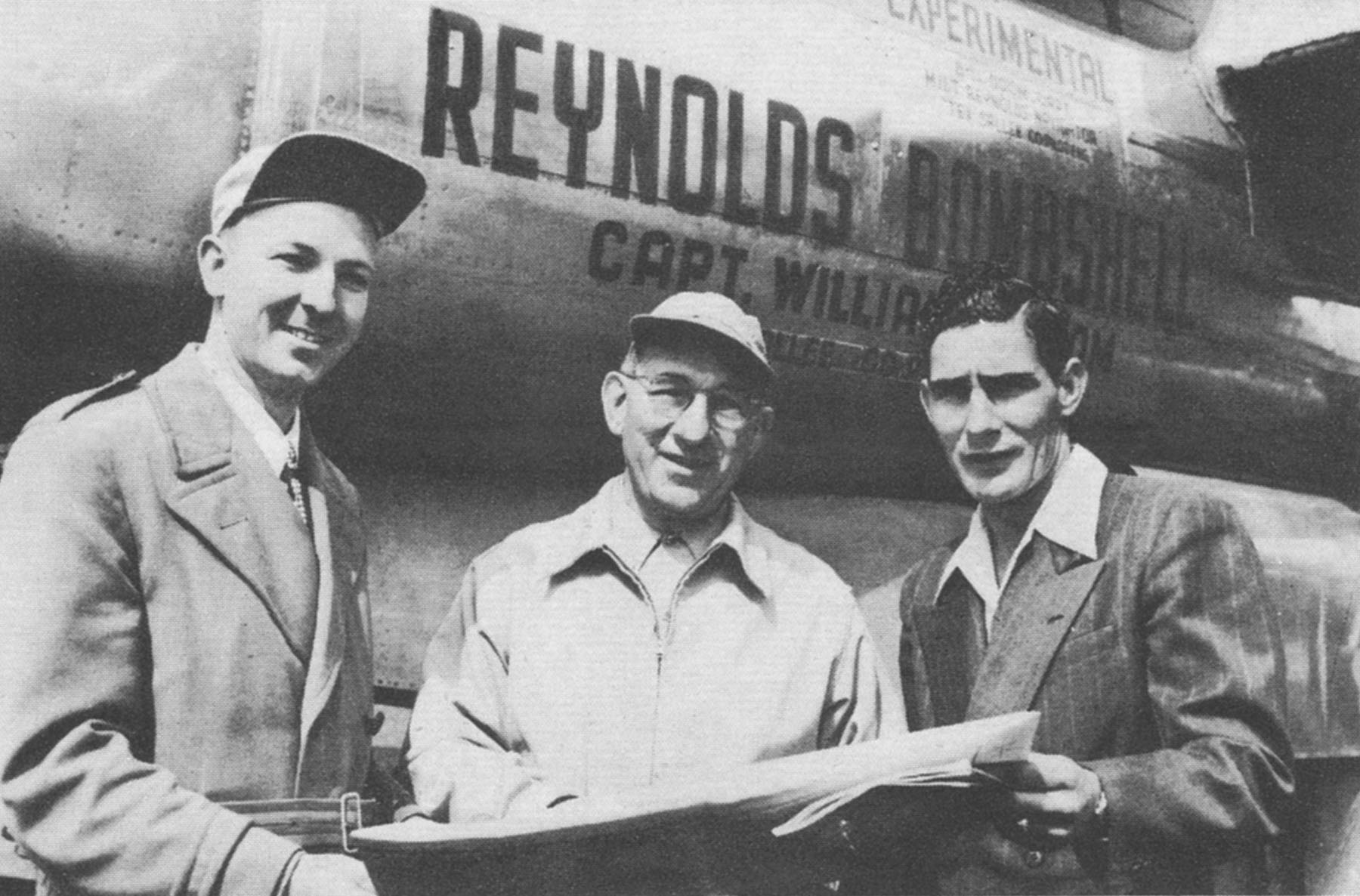

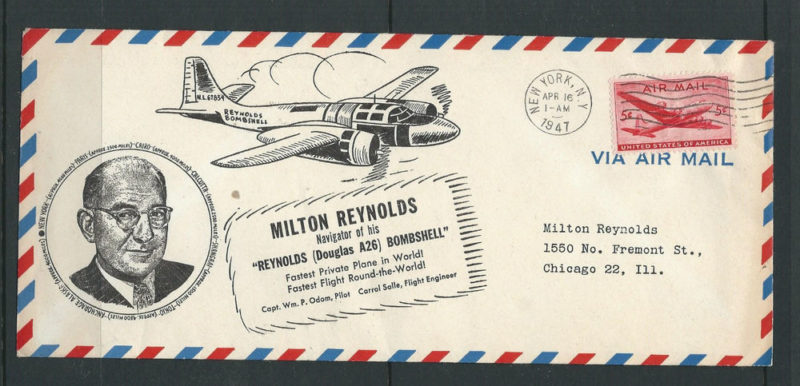

Additional profits were invested in a Douglas A-26 Invader, an attack bomber that had played an important role in the Allied victory. After stripping it of armor plate and cramming it full of gas tanks , he rechristened it “The Reynolds Bombshell.” The plan was to circle the globe, beating out Howard Hughes’s 1938 record of 91 hours, 14 minutes. Willam P. Odom, a China “hump” flyer. was hired to take the wheel. Milton (who lost thirty pounds in order to fit through the narrow cabin door) came along as navigator, “a euphemistic way,” noted Time Magazine, “of spelling ‘passenger’.”

Taking off from La Guardia field, the Bombshell crossed the Atlantic in a record 5 hours and 16 minutes, landed in Paris, then roared into Cairo and Karachi, with Milton handing out pens (guaranteed not to leak at 20,000 feet) at every stop. To the surprise of almost everyone, Hughes’ record was broken, by more than twelve hours, a feat made even more astounding by the fact that the Bombshell had been forced to fly some 5,000 miles out of its way; Reynolds had been unable to obtain permission to fly over Russia. (Nineteen months later, Odom would break the World Record for Distance in a Straight Line when he flew from Honolulu to Oakland, California.) Ever the promoter, Reynolds made sure there’d been room aboard for “collectible” pre-printed, autographed envelopes that read: Carried in the Reynolds Bombshell on the record-breaking solo flight around the world.

Two days after the plane landed safely back home, Manhattan newspapers were running ads for the Reynolds Bombshell, a hydra-headed, 98-cent model that wrote in both blue and red (“two pens in one!”).

President Truman invited the flight crew to the White House and posed with them for photos.

The record-breaking stunt, part Hollywood, part Ringling Brothers circus, part luck, part endurance, had cost Reynolds today’s equivalent of nearly two million dollars, but from his point-of-view, the White House photos alone were worth a million in “free” publicity.

Reynolds’s high profile was now inspiring thousands of inferior pen rip-offs. Some banks were refusing to cash ballpoint-penned checks, claiming that they made it easy to “transfer” signatures. Plus, ‘SatinFlo’ had a tendency to fade on paper, especially in sunlight, though not on the shirts, jackets and dresses it was staining. Disgruntled customers began sending Reynolds their cleaning bills, along with their damaged laundry.

Another rival, blessed with Milton-like dramatic flair, lost no time taking up the challenge. Armed with a newer ink formula (concocted by an unemployed chemist in his cubbyhole home lab). Patrick J. Frawley, Jr. started his own pen company and initiated Project Normandy – homage to the 1944 Allied storming of Normandy beach—to promote it. His salesmen were instructed to barge into retail store buyers’ offices and scribble all over the executives’ shirts before they had a chance to object. This tactic came with the promise that the already-compromised shirt would be replaced with a more expensive one if the ink didn’t completely wash out.

Undaunted, Reynolds developed a gold-plated model, one that glowed in the dark, and another that doubled as a perfume dispenser (guaranteed to exude scent for five years).

But more grandiose plans were afoot.

In 1948, Reynolds organized an expedition (with the Boston Museum of Science as co-sponsor) to search for Amne Machin, a Chinese mountain said to be taller than Everest, the existing world record holder.

Tradition had it that potential exploiters of the hitherto-unexplored sacred peak would wreck divine vengeance in the shape of hailstorms and worse. Milton purchased a C-S7, re-christened it The Explorer, and headed out. In Shanghai, the plane developed engine trouble and the mythical hailstorms materialized, forcing the venture to be cancelled. Two days later, Milton disappeared—with the plane. Fourteen hours later, he was back in Shanghai, claiming he’d had it repaired by the Chinese Air Force. The Chinese scientists, who’d been allowed to accompany the expedition as part of the deal, weren’t buying it. Reynolds, they insisted, had obviously double-crossed them, flying over the sacred peaks without them. When news of the story reached the USSR, a Moscow radio station accused Milton of scouting aloft for uranium in the service of American imperialism.

The story gets a bit muddled after that. The Chinese government may or may not have impounded the plane and arrested Reynolds. Milton may or may not have announced to the local press that he was thinking to set up a pen factory in China, with profits going to Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s New Life Movement.

“Chinese poets are inspired by mountains to write poems,” protested a Peking newspaper editorial, and painters to paint landscapes. The Chinese artist “can lie on his back and dream …. Now we have Mr. Reynolds, holding an atomic pen in his hand…. using mountains to publicize his name!”

In short order, Milton landed in Tokyo, where he could be found handing out pens to everyone from customs authorities to geishas. He claimed to have diverted the outraged, tommy-gun-totting Chinese authorities who’d surrounded his plane by climbing aboard with his pilot under a ruse, slamming the door shut behind them, gunning the engines, then tossing handfuls of gold-plated pens out the window (as a diversionary tactic) as he taxied down the runway.

The China expedition cost him $250,000; in the end, he had little to show for it; after a mostly extraordinary three-year-run, it was time to get out of the game. But not before issuing the Reynolds Flyer, guaranteed for twenty-five years; to emphasize the Flyer’s longevity, Milton sent one to a man serving a life sentence in Sing Sing.

An unlikely progeny was waiting in the wings.

Back in 1888, a Philadelphia man whose name has been lost to history invented a zinc-based paste he trademarked under the name Mum (as in “mum’s the word,” personal hygiene being an infelicitous subject.). The first commercial deodorant was born; aluminum chloride was added a few years later. Packaged in jars and applied with fingertips, application was a messy business.

Half a century later—shortly after Reynolds moved on from the Pen Wars—a Mum company employee by the name of Helen Barnett Diserens developed a “delivery system” based on the ballpoint, one that worked “upside down.” Launched in 1952, Ban Roll-On was an overnight success that quickly went international.