It’s sometimes easy to forget that our technologically complex world wasn’t created out of whole cloth. Or that it wasn’t always here. Without an awareness of the past, “the sense of time falls in upon itself,” writes Lewis Lapham, “collapsing like an accordion into the evangelical present.”

“Vintage Tech,” a column by B. Alexandra Szerlip, will examine some of the under-the-radar stories, personalities and techniques that inform our 21st century lives.

When it comes to revolutionary technologies, it’s hard to top the invention of ink. Book conflagrations (the Mayan codices, the Luftwaffe’s bombing of the British Library, the 2003 bombing of Bagdad’s Grand Library, etc.), assaults against newspapers, and the murder of scholars, publishers and journalists—all speak to its power.

But hand in hand with the evolution of written records has been an evolving counter-technology that both records and conceals—one that has informed everything from innocent diversions and amorous liaisons to espionage and the fate of nations.

Ovid (43 B.C.—A.D. 18), a noted ladies’ man, counseled married women to write illicit love notes in “new milk,” which could be read by adding a touch of coal dust. Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder, who preferred flesh to paper, favored the juice of goat’s lettuce (tithymalus), a medicinal herb, for writing on his lover’s body. Coal dust, redux.

Opponents during the Greco-Persian Wars (499—449 B.C.), adopted a “long game” tactic. The head of an illiterate slave was shaved, his scalp tattooed with secret messages, then the hair was allowed to regrow. Upon arriving at his destination, the head was re-shaved, and read. Technically invisible. Good for one-time use.

Aeneas Tacitus (4th c. B.C.) recommended that, in time of war, a pig’s bladder be inflated and written on with a mix of ink and glue. Once dry, it should be deflated and forced into a glass flask, which was then filled with oil and corked. The recipient had only to pour out the oil and re-inflate the bladder to read the text.

In 1525, Venice’s secret police paid cypher master Marco Raphael the equivalent of a years’ salary to develop new “smart ink” recipes. A few years later, an intriguing volume, credited to Florentine poet-calligrapher G.B. Verini, appeared. A veritable toolkit, it included blank pages requiring the application of charcoal, others calling for lemon juice, plus a bone (for rubbing) and a mirror (for reversed writing). There’s no record that Verini suffered for his efforts, but Giambattista Della Porta wasn’t so lucky. Timing, as they say, is everything.

Della Porta’s Magia Naturalis, an international bestseller, cut a broad swath—from optics, magnetism and meteorology to invisible ink recipes (one called for juices from a dormouse), instructions for an unguent used by witches, and advice to the incarcerated: Write on the shells of hard-boiled eggs with a mixture of alum and vinegar. Thus painted, the message will seep through and transfer onto the egg’s albumen, where it can only be read once the egg is peeled. Hidden messages, unless one knows what to test for, will never be suspected, thus providing “great obscurity in affairs of greatest moment, when concealment is no small advantage.” The Inquisition was now well underway. Eggs, he claimed, fell beneath its radar.

Not so Magia Naturalis. Called to appear, twice, before the Holy See’s tribunal (and aware that fellow countryman, Giordano Bruno, had been burnt at the stake for merely insisting that the earth spins around the sun), Della Porta hightailed it underground, disguised in Jesuit robes.

Black ink—a mix of crushed gall nuts (parasitic oak tree swellings), gum arabic and “vitriol” (a sulfate of copper, iron or zinc)—was nothing new. Bach composed with it, Van Gogh drew with it, da Vinci and Shakespeare wrote with it. But writing with gall nuts and water alone was another “invisible” method. An anonymous Brit would later compare the effect of rubbing a gall nut text with the missing vitriol to lightning bursting out from a cloud.

“Writing in white” was a favorite of Mary Queen of Scots during her protracted plot to usurp the throne from her red-haired cousin. Though “such artifices be very hazardous and vulgar,” she wrote to the Bishop of Glasgow, “they will serve me in extreme necessity.” Which they did, until Elizabeth I’s spymaster, Francis Walsingham, having already broken Mary’s cyphers, got wise to the ruse.

In 1736, with popular science much in vogue, Jean-Jacques Rousseau thought it might be fun to cook up his own disappearing ink batch using quicklime and orpiment (an arsenic sulfide). The subsequent explosion blinded him for the better part of two months.

Things took a more promising turn with changeable landscape fire screens—a technology made possible by the discovery of a rose-colored salt containing bismuth cobalt, which turned blue with heat but disappeared when cooled. A landscape of bare trees and branches was painted with India ink. Then over it, lush scrubs and greenery were created with a solution of cobalt chloride. Acetate of chloride was used for the sky. When heat from a fire warmed the screen, the bare winter landscape transformed into a verdant scene. When the heat receded, the barren trees returned.

Cobalt chloride ink was soon being sold as l’encre sympatique (so-called because it seemed to work “in sympathy,” e.g. for unknown reasons), marketed to women—Ovid would have approved—with a penchant for clandestine correspondence.

The fire screens, all the rage in Paris, eventually made their way to England, where they inspired Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus, to poetry:

Thus with Hermetic Art, the adept combines

The royal acid with cobaltic mines;

Marks with quick pen in lines unseen portrayed

The blushing mead, green dell, and dusky glade;

…

Till, waked by fire, the dawning tablet glows,

Green springs the herb, the purple flower blows…

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, George Washington was busy finding ways to combat Darwin’s countrymen on the battlefield. He could, he wrote one of his commanders, obtain a liquid—“a sympathetic stain… which nothing but a counter liquor [e.g. ferrous sulfate} can make legible. Fire… has no effect on it.”

Realizing that a blank sheet would arouse suspicion, he instructed his spies to write seemingly banal letters “in common ink” between the lines of their secret messages or on the flaps of innocuous pamphlets. His spies, in turn, referred to invisible writing as “concealed beauties” that “the cursory observations of a sea captain” would never discover. And as “diamonds.”

So dependent was Washington on his “medicine” (gallotannic acid) that he arranged for a small log-cabin lab, complete with brick furnace, to be built near his headquarters.

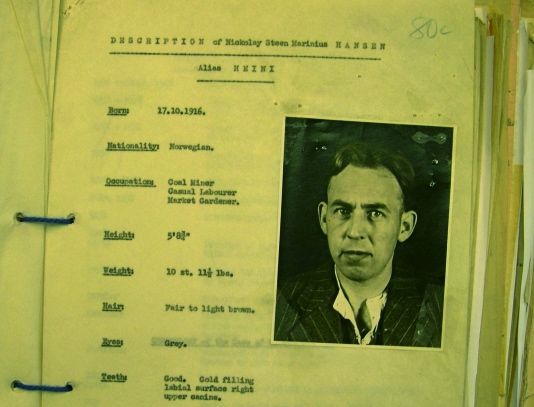

During WWI, Germans embraced disappearing ink as a primary espionage tool. One particularly notorious spy, an aristocratic, mink-and-jewel-encrusted Prussian blonde, carried sodium nitrate-impregnated silk scarves and mufflers that she moistened in cold water and wrung out. Collars, ties, shoelaces, and lingerie were used in similar fashion.

Lemons had been a go-to favorite for centuries. Any slightly acidic liquid (vinegar, unripe white grapes, milk, urine) disappears into, and weakens, paper fibers. Applying heat turns those fibers brown more rapidly than untreated ones.

After the British executed eleven German “lemon juice” spies in 1915, Germany expanded its arsenal—crafting inks from aspirin, a headache remedy (pyramidion), even laxatives containing phenolphthalein. One clever formula required activation by blood—the agent pricked his finger and added a drop into the mix before writing.

British military intelligence, meanwhile, had high hopes for semen. On the plus side: An ever-ready supply that didn’t react to the newly perfected iodine-vapor test (which revealed paper fibers that had been altered by any kind of moisture, acidic or otherwise). On the minus side: If not “freshly extracted,” it smelled. But most damning was that its use raised questions about the masturbatory habits – done in service to His Majesty! – of Britain’s secret agents.

Fast forward to WWII. So confident was Germany of outsmarting the Allies—who, as late as 1940, considered post office scrutiny by the military taboo under the premise that “Gentlemen don’t read each other’s mail”—that Nazi spies were often outfitted with the same primitive inks employed a generation before.

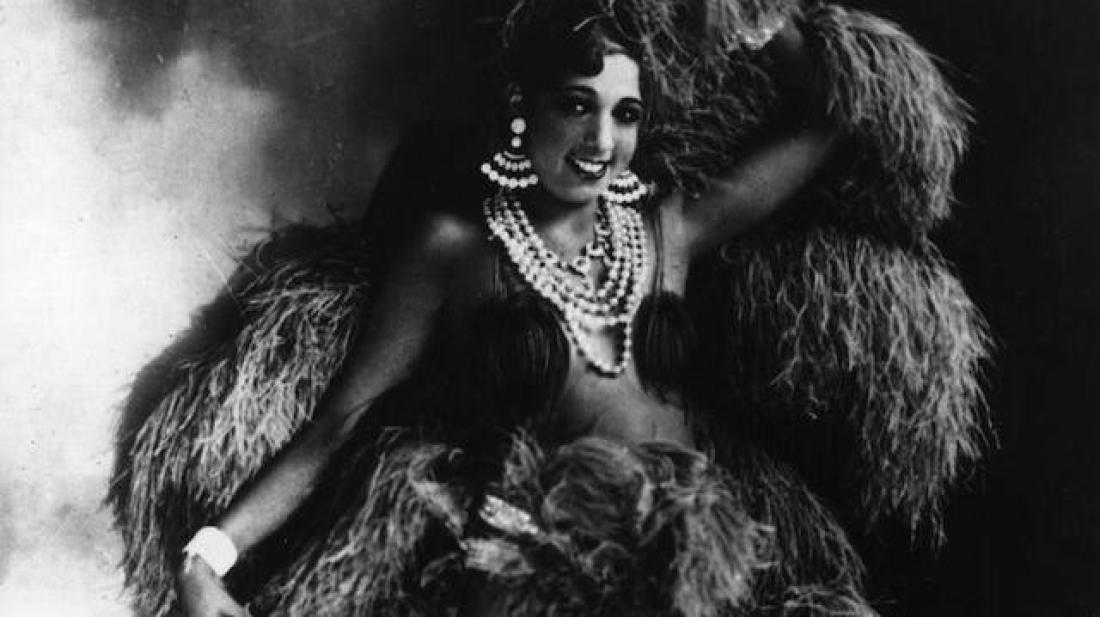

On tour across Europe and South America, Josephine Baker “played the sexy dingbat” (as one biographer put it) eavesdropping at embassy parties, all the while making detailed notes in invisible ink on her sheet music. (She also smuggled photos of German military installations pinned to her underwear.)

In the 1950s, with the Cold War raging, the U.S. was still using antiquated ink recipes (as their German counterparts had done) – methods, complained one CIA chemist, that “Caesar could have used during the Gallic Wars.” In the name of national security, Nobel Prize winners and MIT professors stepped up to the plate, experimenting with ink-based pneumonia bacteria and radioactive isotopes.

Invisible ink’s heyday ended with the advent of microdot technology, which can shrink a text to one-four-hundredths of its original size.

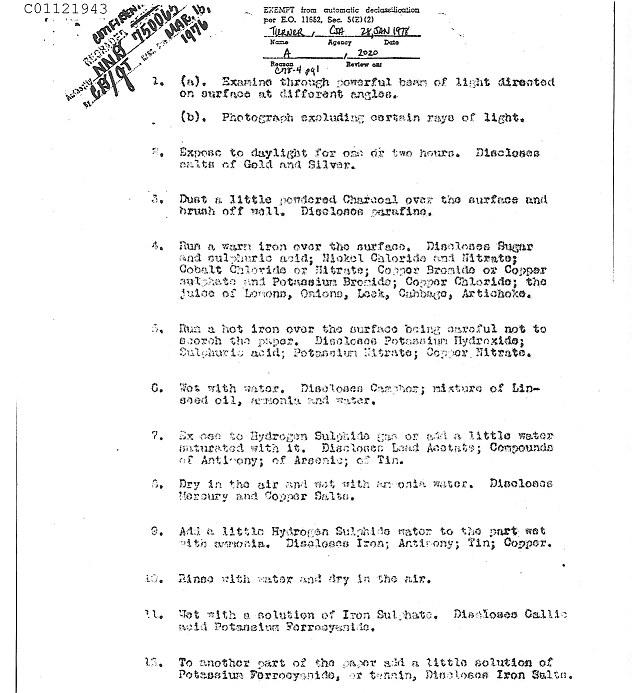

And yet, despite repeated requests under the Freedom of Information Act, the CIA has been reluctant to declassify even century-old documents pertaining to secret writing. Those that were finally released, in 2011, consist mostly of information readily available on the Web and in Boy’s Life magazine. (Far more interesting are Britain’s MI6-released documents on Nazi assassination devices ranging from the silly to the terrifying.)

Most people, today, think of disappearing ink as a childrens’ pastime, but the allure and mystique remain. Both Herbin (French) and Noodlersink (American) offer invisible-by-day, UV-activated, phosphorescent fountain pen inks, presumably to an adult market, formulas so sophisticated as to be “bulletproof,” meaning they can’t be washed away by water.

In 2008, the technology was commandeered to secure election ballots, a system called Scantegrity, with voters using what look like 1950s, cereal-box “decoder” pens.

In 2017, Chinese scientists announced the creation of a new, truly undetectable invisible ink that “reveals,” under UV lights, after an application of a special salt. One caveat: it may be toxic.

Just this year, the Tokyo-based Pilot company released the FriXion, an erasable gel pen. The eraser’s friction heats the thermo-sensitive ink to 140 degrees F., rendering it invisible. Though not what the inventors had in mind, the FriXion allows users to write a message, then erase it (with the provided eraser, a quick stay in an oven, proximity to a hot object, or possibly in a summer-heated car), knowing that the message will “reveal” only after being cooled to about 14 degrees F. (Try your freezer.)

All that said, consider another kind of invisible text.What’s to become of all your emails and Tweets? Paper can survive for hundreds of years; the average life of a Web page is estimated at a hundred days.

How will future historians and biographers manage?

As for cloak-and-dagger in our age of unprecedentedly sophisticated spy craft, who knows? The archaic, time-tested, low-tech methods might just be the ones least suspected.

Now, about that negligee I’m rinsing out in the sink…