My friend the writer Chris Benfey and I have for many years had conversations about chance, coincidence, and serendipity. Last summer we decided to have a correspondence on those themes. What started as a casual private back-and-forth soon enough found momentum and led to 100 exchanges (we agreed to that number as a cap). What follows are several excerpts from the opening volleys, here on influences of James Joyce, Seamus Heaney, and Wittgenstein on our thinking.

—Sven Birkerts

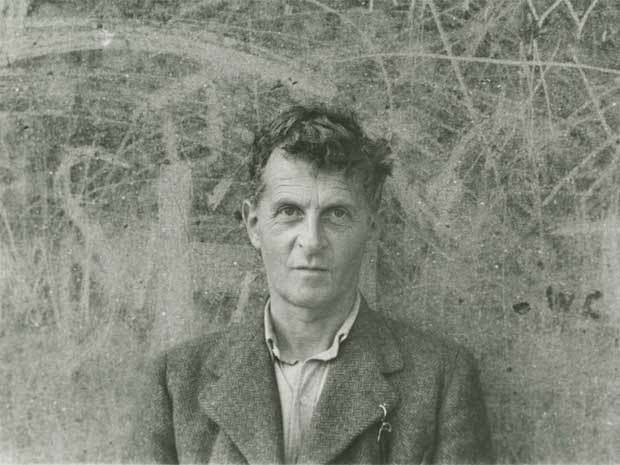

CHRISTOPHER BENFEY: You asked about loading the dice to encourage serendipity. As you know, in preparation to our trip to Ireland I’ve been reading about Wittgenstein’s time there. I found out in some article that Wittgenstein read Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man there, and that he particularly admired the long section on the Jesuit retreat. But what really moved me, in my haphazard research, was discovering Wittgenstein’s passion for the birds of Ireland—especially once he’d shifted his base of operations to the West of Ireland, and the coastal region around Killary Harbor, which he called, fondly, one of the last “pools of darkness” in Europe. I was delighted to find that my wife Mickey had booked a couple of nights within a half hour’s drive from Killary, so I might be able to visit the remote cottage where Wittgenstein lived and take a look at those birds myself.

Last night, I picked up Portrait, which I haven’t read since college, hence haven’t read, and patiently worked my way through the retreat section before flipping through the back pages. My eyes alighted on a passage I’d marked, as an undergraduate, “birds.” Stephen Dedalus, named for the craftsman of artificial wings, is thinking of leaving Ireland and the church, and he is fixated on a flock of birds, a dozen or so, shrill (the word is used four times in a couple of pages) and dipping here and there. He thinks of augury, divination via bird flight, and identifies his own trajectory with the birds for leaving their temporary nests, as he will soon leave his. Joyce specifies that Dedalus witnesses these swallows on Molesworth Street. The name rings a bell. I ask Mickey if that’s where our Dublin hotel, Buswells, is. She confirms that it is.

Loading the dice here entails something like this. I do some scattershot research on Wittgenstein in Ireland, inviting his sojourns there to haunt my own. “Nature is a haunted house,” writes Emily Dickinson. “Art is a house that tries to be haunted.” The main move, or throw of the dice, on my part is to follow Wittgenstein’s lead into Joyce’s Portrait, with some vague hope or trust...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in