“I think ultimately art will be the last science. Once we’ve come up with virtually all the answers, the one thing that we will still not understand is creative expression.”

Things on John Reed’s Desk:

Microphone

Computer

Bunny Puppet

Another Bunny Puppet

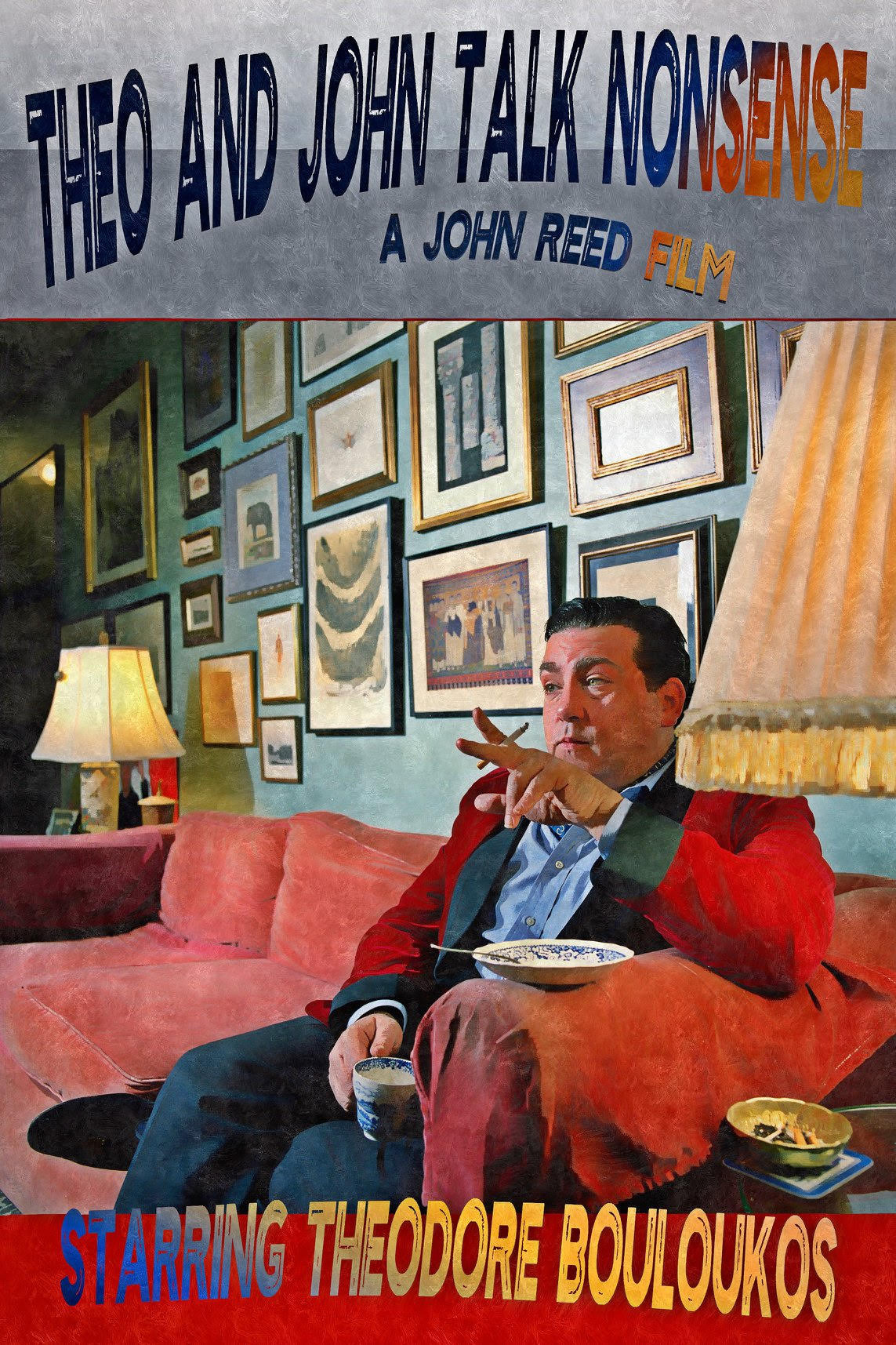

John Reed is a third-generation New Yorker, a second-generation artist. I admire the joker in him, or what he has described as “the criminal, or more aptly, the artist in all of us.” He’s created six books of prose and poetry, including Snowball’s Chance, a parody-sequel to Animal Farm written after 9/11, in which the forest creatures rise up against the capitalist farm animals and destroy twin windmills. In Free Boat, he takes aim at love, character, fiction, poetry, and linear time (Free Boat, he jokes. The last sign you’ll ever see). According to his satirical novel, The Whole, all of Reed’s books are actually written by a snarky ex-girlfriend. According to his publisher’s bio, he’s dead.

I meet Reed on a rainy October afternoon at the Tribeca Tavern, on the block that inspired his most recent project. He points out the former site of the fabled Magoo Tavern: it’s now a giant pharmacy. Behind us, locals discuss corporate politics and destination weddings. In the 1970s and 80s, Reed grew up here, on a very different kind of block.

In The Sky Is Blue With Lies: Tribeca Phaedra, Reed reimagines Euripides’ incestuous love-and-revenge story in the 1970s Tribeca of his childhood. Nine bargoers—a modern Greek chorus—tell the tragic tale of a Phaedra and Hippolytus (now 20th-century New Yorkers, Fara and Po).

The film is a no-wave mash of interviews, narration, and what looks like scraps of 1970s home videos. The Greenpoint Film Festival categorized it as a documentary. “Documentary?” I asked. True to form, he is both frank and obscure. “It’s 90% documentary,” he explains. “Wait”, I say. “You mean: Fara and Po are real?” “Oh no,” he says. “That part is made up. But everything else is real.”

We adjust the mics to tune out the din of the bar. “I wouldn’t want any scandals,” he jokes, and we laugh. Scandal is the order of the day right now. Yes, yes, I laugh, too. Of course not. But the thing is, I do have a question I need him to answer, and I’m not sure how it’s going to go.

I want to talk to him about his recent film, artist collaborations, and decapitalizing creativity.

I also want to ask a more difficult question, about remaking narratives from cultures in which women didn’t tell their own stories. Specifically, about remaking the story of Phaedra. He’s game for the conversation.

This transcript is the edited result of our chats, over the course of which Christine Blasey Ford testified to Congress, and Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed to the Supreme Court. This wasn’t planned, but all the same: Phaedra and Hippolytus feel painfully current.

We have a lot to talk about.

—Katie Peyton Hofstadter

I. “The Bar Owner Is the King of the Village”

THE BELIEVER: How did you choose the Phaedra story?

JOHN REED: T.S. Elliot talks about the object correlative, where you can arrive at an emotional state through storytelling. I thought I could use the Greek Phaedra to bring back an emotional state akin to 1970s New York, specifically TriBeCa.

BLVR: It’s nice to chat with you about it here, on this block. What was it like in 1979?

JR: This [pointing] was Leroy’s Diner, and it was a floor-through just like it is now. What else? LeRoy knew me, I would go in there and he’d make me peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. I had a tab.

There was a bad liquor store right here, and there was a really bad liquor store on the other side of the block. It was a block with two liquor stores. Over there was an empty lot, where we played baseball.

I lived in the building behind this building.

BLVR: What was it like living on that block?

JR: This corner was so freezing cold. It was the coldest corner in New York City. You would just stand there waiting for the school bus, and whatever you were wearing, the wind would just inflate you.

That was the Farm & Garden Nursery. On Christmas Eve, the kids in the neighborhood would stand on the crate, and the guys would throw the Christmas trees at you. If you could stay on the crate while they threw the tree at you, you got to keep it.

Magoo’s was on the corner, over there where the pharmacy is.

BLVR: In 1979, you were ten.

JR: Yeah. Magoo’s made an impression on me. In the script, I don’t use the name. I wanted anyone to think of their local bar. The bar owner is the king of the village.

I mean, the Mudd Club was a couple of blocks away. Magoo’s was the preexisting scene, before all that. It was like the mossy ground where things sprung up. It wasn’t like that heavy East Village influence-y stuff. It was the second generation of ab-ex people as well as the beginning of that burgeoning Tribeca scene.

That’s the beauty of New York City, right? That anything you really love in New York City will be destroyed.

There was an amazing art collection at Magoo’s.

BLVR: Tell me about it.

JR: The owner, Tommy, would trade with artists. There was a dynamite painting by my mother. I remember a John Torreano piece, Ron Gorchov. My father had a piece in there. I believe I remember an Elizabeth Murray.

Oh, I don’t know if it still happens, but clouds would stick to this AT&T building. Literally, it’d be a sunny day, and it would be raining only on that building.

BLVR: Wait, what? Really?

JR: Sometimes buildings have magnetic fields. I always thought it was magical. I might have it slightly wrong, but somebody explained to me that sometimes there are buildings that clouds can stick to.

BLVR: I suppose if we put big enough things in the sky… it makes sense that weather would react with them.

JR: It’s actually a really, really beautiful building if you ever go inside. I don’t know if it dates to an art deco period, but it feels art deco on the inside.

II. Art Will Be the Last Science

BLVR: Even though the film is based on the myth of Phaedra and Hippolytus, it was categorized as a documentary.

JR: The line between fiction and nonfiction is always moving. There’s a moment when you’re shooting something, and the cameras stop and everybody comes alive.

In the interviews, I did every sneaky thing possible to try to get living performances. You have people coming to life the second you say cut. I would tell the actors, Okay, we’re just going to do it once without the cameras. Turn off the cameras. Or I’d say, Okay, Kevin [the DP], when I say cut, don’t cut. We had hand signals.

People tell stories about other people but also, they’re talking about themselves. Everybody’s talking about their own experience and their own path to some sort of enlightenment, some kind of better version of selfhood.

[An ACE train rumbles by, loudly. We are now shouting.]

JR: I honestly don’t know if the film is a documentary. The Phaedra story, is fiction. But the internal story is all drawn from people’s real lives. None of that stuff is scripted. I mean, I don’t know if it exactly fits in documentary, but I guess it could fit in experimental documentary.

BLVR: How so?

JR: I cast two different kinds of actors. The four scripted actors don’t look like other people. They look like film creatures.

The others, the Greek chorus, were downtown celebrity types. People I could imagine in that time and place. Those parts were directed improv. Though they had a few scripted lines, as well.

The structure of the script was just a series of numbered questions, with a few scripted lines.

A few people told me there was a Godard film which was structured this way, teasing out a narrative from interviews. I haven’t seen it.

BLVR: There’s a similar question in artificial intelligence. If you feed a machine enough data points of memory from enough people, can you reconstruct a person? Or will you always feel like you’re looking at something fractured and robotic?

JR: You know, science claims to be shrinking art, and science claims to be shrinking God. So science has all these claims on our consciousness and yet, really science has explained nothing in terms of our actual consciousness, the components of it, piece by piece.

I think ultimately art will be the last science. Once we’ve come up with virtually all the answers, the one thing that we will still not understand is creative expression. That’s because creative expression is not mutually exclusive. It can contain contradictory experiences in it. You can have different interpretations of one thing. You can have an emotional state that encompasses very, very conflicted responses. The arts right now, of course, feel like they really take a second seat to our technological obsessions. My guess is in the end, that’ll be the last wink of our existence.

III. “The Gods Have Gigantically Human Emotions”

BLVR: So, in the film, the story is told by the Greek chorus, who are the bar-goers to the Magoo tavern. What actually happens in the film?

JR: Fara falls in love with her stepson Po. Candy [the Aphrodite character] gets jealous and tells Po’s father [Fara’s husband] that Po raped Fara and… then everybody dies tragically.

BLVR: What is your thought process, when you are translating ancient gods into modern humans?

JR: That’s a really interesting thing. There are two sets of characters in those Greek myths, typically. There are the gods, but the counterpoints are these servant characters, the general or the handmaid.

The gods command the action, but weirdly, they don’t actually carry out the curses. The servant characters do.

The gods name the curses; they decree fate.

The gods have gigantically human emotions somehow, overblown, and their vengeances are so petty. Donny won’t even admit that he pushed Po out the window.

BLVR: Right! But before that, a Greek chorus member / bar-goer tells an unscripted story about a cat that went out the window. It was almost a perfect mirroring of how Po dies. Did you know you were going to get that story?

JR: No! I couldn’t believe it. We were actually just talking about breakups when she started talking about the cat. She passed over it and I was like, wait. You can hear the edit.

BLVR: You said, “Tell me about the cat.” And she said, “Let’s just say the cat went out the window.”

JR: When I was a teenager, someone from my high school fell out a window. That was always a little suspicious to me. Then of course, there’s Ana Mendieta. I remember when that happened and obviously she didn’t fall out the window. In a way, it’s a perfect crime. Just push them out the window.

BLVR: What changes have you made to the traditional myth?

JR: I’ve pretty much stuck with the normative version. Aphrodite got jealous of Phaedra, because she didn’t need love, and cursed her to fall in love with her own stepson.

BLVR: Candy claims Po raped Fara; Fara kills herself before anyone can get her side of the story. What happened between Fara and Po?

JR: I read it as nothing happened. I like that you don’t really know. That’s my read on it, which is very in keeping with the Greek versions. Phaedra really pushes it to happen, and it doesn’t happen. She’s rebuffed.

My take on it is that Candy was ultimately rebuffed [by Po] and her rage was manifested in this lie. Candy was being manipulative. She saw that there was more between Fara and Po than she would ever have. She was punishing Fara for not wanting anything.

BLVR: If nothing happened, why did Fara commit suicide?

JR: Because—I think there’s just no going back. What, now she’s going to go back to that shitty thing she had before?

To me, that was the ultimate punishment of being a mortal, that it’s impossible to go back. I don’t know if it was an intentional suicide or just an overdose. But there’s no going back. She can’t go back to the Adirondacks or to the Catskills and pick up where she left off. She’s come too far.

BLVR: I want to read a scripted line from Donny: “You see kids like Fara, skinny kids but with eyes like stones, you see them when you drive through that town that’s got old Chevys for sale in a couple driveways, and abandoned cars and lawnmowers on the lawns.” Donny is describing people who are getting out, leaving a place they aren’t going back to.

JR: Yeah. There’s just no place for her anymore.

IV. Retelling (Very) Old Stories after #MeToo

BLVR: Looking at the film, there’s something else troubling me about that suicide and the alleged rape story. This is a film that you made before the #MeToo era, and it came out during the #MeToo era.

JR: That hadn’t even occurred to me.

BLVR: One argument is that Phaedra and Hippolytus is a story about moderating the poles of our emotions. But in practice, the “Phaedra” story is more commonly invoked as a cautionary tale against believing women.

JR: Oh, that’s true. That’s terrible. I hadn’t thought of that at all. See, this is the thing. Nobody believed Po raped Fara but Donny.

BLVR: I did.

JR: You thought he did it?

BLVR: Well… Fara killed herself afterwards. If nothing happened, why?

JR: It is part of the Greek myth.

BLVR: Yes. But I also thought, that myth was set down at a time when women didn’t tell their own stories.

JR: Yeah. I feel like it’s just a story of human failings on so many levels.

I wanted Fara to be the one character you definitely fell in love with, the one character that you really felt, this was her tragedy.

I switched it to being her story… the Greek versions are focused on Hippolytus, and the more modern versions are focused more on Phaedra. She’s more interesting as a character.

I’m having trouble taking it out of the Greek myth and applying it forward. It’s such a story about fate. It’s also hard to take the #MeToo movement out of social media. I have to think about that.

BLVR: It’s hard not to see the Phaedra story in the Kavanaugh hearings. Greek myths are almost like this holy book of culture. We look back at them for psychological archetypes and our deepest stories. But when you remove the supernatural element from Phaedra, it seems like a pretty plausible story of rape and PTSD.

JR: It’s true. It fits. I don’t know. It is really hard to take when you’re reading older versions. I find it really hard to believe, too, to be honest. I appreciate you challenging me. You and Donny have a convincing argument. I wanted to make it plausible that he could have or couldn’t have.

It’s funny hearing you talk about it. It really forces me to analyze it. You might have convinced me.

Now I’m glad I left it ambiguous. I like leaving it up to the viewer to decide. Maybe the more important thing was just to create a complex situation people could believe.

V. Failure, Resistance and Collaboration in the Arts

BLVR: Let’s talk about other ideas. At a panel last week, there was this lovely moment when you said that being an artist is to fail.

JR: It was interpreted at the panel as, you have to be willing to fail in order to do things.

But what I was talking about specifically is this. You choose your medium because you feel like it hasn’t done something.

If you’re a writer, you want to take text and make it do this new thing. The process of maturing as a writer is, of course, realizing that text can’t do what you want it to do. Whether you’re a painter, or a writer, or a sculptor, or whatever. The process is coming to terms with the limitations of the medium. That said, you can make it come closer.

If learning to be a writer is learning that language fails in a certain context, it’s also making it come that much closer to succeeding.

Of course, language can’t do the thing we want it to do because it’s not experience itself. So no matter what medium you’re working in, ultimately, you won’t be able to turn it into experience itself. That’s what I was talking about, but I also appreciate the idea of just try again, fail better.

BLVR: I did notice that it was a male moderator with three male panelists talking about two male artists.

JR: I noticed that too. Also, what about the women of the period? Why haven’t we remembered them? There are so many amazing painters. Of course I would name my mom [Judy Rifka] who, obviously, was a part of developing that iconography in the period.

I love those Christy Rupp rats. It’s pretty clear to me that she was a defining factor in shaping how the dogs took shape in Keith Haring, how all of those animals filled in that East Village vocabulary of images. I don’t know. I like Jenny Holzer okay, but I feel like there are painters who are amazing from that period, who are woman. If you’re looking at Damien Hirst, I think about those Debby Davis fetal pigs. All of her weird, horribly creepy, and extraordinary taxidermy stuff that she did in that period. There are so many examples. It’s odd to me.

[Another ACE roars by. The sidewalk is shaking a little bit.]

BLVR: You remade a story that’s at least 2,400 years old. What do you think hasn’t been discussed?

JR: I definitely wanted to shake up some ideas about class. I think that element has been emptied out of it. We don’t talk about class anywhere.

It’s been emptied out, and not only from that story. It’s now endemic to our culture. The fact that Donald Trump can be this hero for the working class when, obviously, he doesn’t represent them. The buy-ins to participate in culture, these academic justifications where you must have the right degree. It’s very, very hard to participate without that academic license, and all of that academic license functions to normalize the conversation. In doing so, we stop talking about class. Class is completely a non sequitur in political conversations.

It seems like the great oversight of our moment. We’re in this consumer market that just has to assume that you’re aspirationally charged. Without that, you just don’t even get to talk.

On both the left and the right. There is a feeling that radicalism—independent thinking if you’re a Republican, or radicalism if you’re on the left—it always has to be attached to your aspirational endeavors.

[An M55 bus pulls up a few feet away.]

BLVR: Tell me more when the bus goes away?

JR: Whatever change you want to effect has to be connected to your own aspirational endeavors. You have to want to climb the ladder to be able to make a cultural criticism, which is really pretty limiting when you’re looking at a broader conversation. You have to be compromised as a critic to be taken seriously.

BLVR: Recently we were talking about forgeries. Valuing and devaluing. It keeps working itself into the conversation. You recently wrote about decapitalizing art. Can you talk more about that?

JR: I’ve been cursed with being maybe commercial enough at times. I’m optimistic that maybe with the next project, they’ll get a few copies out.

We’re told all the time that this art is valuable, this art is meaningful because so many people see it. But really, it is more a function of its category, and the market that exists for that category. Of course art isn’t intrinsically defined by categorical or market values. You can’t really sell love and you can’t really sell art, but you can sell sex, and you can sell stuff.

BLVR: Can you imagine a better relationship between money and art?

JR: I actually think it’s simple: a radical localization of the art market and the literary market. If we functioned in local economies, with fewer hegemonic establishments, we would have a higher level of art and wealth for creative people.

There are five major publishers now. There are five major galleries. The auction houses are running the show.

As a species, we have a propensity to want to reduce our perception of our social circles. We want to think that there are fewer of us on the planet, fewer people of influence. We want to believe, individually: I have a direct relationship to literature and to art, to the canon of creation. That’s really only to inflate our own egos. It’s completely contrary to reality. Completely.

BLVR: How so?

JR: Artists don’t arrive from vacuums, fully formed. They’re in a context. They have friends. They have other influences. But we prefer this conceptual greatness because it allows us to enlarge ourselves with our own fantastical visions of who we are. If we were to localize these economies, we might also get away from this idea of our own self-importance.

BLVR: What would that look like for your own work?

JR: Well, I would love to work on bigger collaborative projects. I think all the time about how to do it. It’s part of what drew me to want to work on films: I could not imagine myself sitting in a dark room churning out another novel.

I’ve been trying to come up with a model for a big collaborative text for twenty years. I don’t know how. I’m out there looking all the time for a platform—just a platform—that would allow you to do that. I couldn’t find anything even close.

BLVR: I’m thinking about the models we currently have: Instagram, virtual exhibitions, endless scrolling images and text. These platforms host art but commodify participation. I’m thinking of what sort of principles could be applied to that model to keep that from happening.

JR: Really, you’re right. There are writing platforms, but they’re not successful creative models, really, they’re social models. The problem is they very much appeal to your vanity. It’s a shrunken community of important people or influencers, which creates celebrity culture and a shallow relationship to experiences. It brings us to the absolute lowest, absolute basest level of what we do, and why we do it. It’s a shitty mindset and headspace.

It doesn’t seem possible that it could happen in those places, primarily for those reasons. I could be wrong. Early on, I thought maybe it could happen in Facebook or Instagram, but it hasn’t happened at all. Not a little bit.

It does allow individual artists to share work, but I haven’t seen evidence of real collaborative projects coming out of those environments.

I also wonder if the need for collaboration isn’t basically indicative of the more primal instinct in human beings. Until very recently, until only 10-12,000 years ago, we were essentially egalitarian societies. Maybe we had leaders. There were smaller groups. If you go back 20,000 years, it’s certainly the case. The kinds of inequities that you see in wages or social strata or standard of living, those things just didn’t exist. We had much more of a collaborative culture.

BLVR: The wealthiest percent weren’t so disconnected from the rest of the species.

JR: Twenty thousand years ago, they were there with them. Now they’re really disconnected. That’s very recent. The kinds of exploitation you’re seeing in the last 2-3,000 years is really extreme, in the last 200 years, for sure. Historically, things are getting better because most people are not living below the poverty line, as they were in the United States through the 19th century, but the wealth distribution in the modern epoch of humanity is not good.

I just feel like as primates, we are set up to collaborate. But we have a media culture that is set up to feed your narcissism.

BLVR: It’s funny, experientially. I know after this I’m going to go write for three hours because having these conversations is so energizing. I don’t know what that model looks like either but…

JR: The only problem, of course, is that the people who want to make models like that also have to make money.

BLVR: Or they don’t, and they don’t last very long.

JR: In a collaborative system, it’s hard to sell crap. Whatever identity you want to adopt, you have to buy crap to fit in with that. East Village, or Hip Hop, anything. It’s your own rapacity and vanity the market appeals to.

Then, there are people on their allowances who have money to start with. I know there are exceptions, but for the most part, those financed artists don’t really get it. That’s been my impression.

It’s a bummer, because everyone wants to work collaboratively.

BLVR: What do we do until then?

JR: Resist continuously. Admire the writers you admire, the artists you admire, regardless of their status of the moment. Which is not how criticism generally functions, of course. Criticism, for the most part is based on this market agenda. Primarily, normative criticism is charged with two tasks: make better, more sophisticated arguments for mainstream propaganda; discover more efficiently, more cheaply produced propaganda, which in turn allows for propaganda to be produced more cost effectively as a whole.

In most ways, as a cultural consumer, I fail. I’m not sophisticated when it comes to music, to fashion. I think most of us are doomed to be pretty base in most of our consumption. But each of us also has areas of expertise, that we can help to elevate. In the other areas, where we’re not so hot, we have to resist received opinions and ideas.

Distrust the hot take, and try to not be cowed by whatever the conversation of the moment is. I think at an easier level, just resist continuously.