“the opposites of things are always very close. There is no humor without death, and the consolation for death is black humor.”

Material that metaphorical knots can be made of:

Images from Childhood

Mother

Dust

I was at a birthday party recently where the children played “Pass the Parcel.” They sat in a circle, and passed around a box colorfully wrapped many, many times. The way the game works is that music is played, the box is passed, and the child the music stops at unwraps ONE layer. This goes on until the whole box is unwrapped and a plastic toy or candy spills out. I watched this game, and as I watched I couldn’t help imagining an endlessness of wrapping. Hours go by, then days, then years. The children grow older. The house gets dusty. Cobwebs are spun. Parents die. But the game goes on. Layer after layer. There is so much wrapping. And as many times as the music stops it begins again. The box grows smaller, but never small enough. The children are old now. Something is inside the box, but each layer only reveals another layer. One old child whispers to another, “I love you.” Another old child writes a book. Another old child grows a beard.

Elizabeth McCracken was at this party. Not the party party, but the party inside my head. It might’ve even been she who wrapped the parcel. Or combed the old child’s beard. Or kept the music playing. What I do know with certainty is she believes in this party. In the old children. In the cake never being served, the candles never being blown out. She believes in the strange and terrifying and beautiful passage of time. This is why she is one of my favorite writers on earth. She knows what keeps everything going is all we cannot see.

—Sabrina Orah Mark

ELIZABETH MCCRACKEN: What do the children in Wild Milk have to do with your own children? I guess I’m trying to ask myself a question at the same time. I write more about children now that I have them than I ever did. But I am adamant that I never write about my children. I wonder how having children has shifted your actual writing practice.

SABRINA ORAH MARK: While writing Wild Milk little pieces of my boys got snagged on the children, the trees, the mothers, the weather, the snails, even the jokes in my stories. Because my boys are about 144% of my air there was no way I was getting out of a story alive without leaving behind (like a note in the crack of a wall) some evidence of their breath. The strange, perfect thing about real children is that they are faster than metaphor. Which is to say, for a metaphor to work one body needs to hold the body of another, endlessly. But with children they’re always bursting out of us, out of themselves. They’re uncatchable. Children defy metaphor because they defy enclosure, shell. The child is to off and to spring. That’s their charge. They are always getting away from us one way or another. Which might be why a child in a cage is one of the worst images on earth.

Before I had children I wrote almost entirely in prose poems. I felt very sure of the walls. There was no escaping those prose poem boxes unless you dug a hole through the center and weren’t afraid of using it to escape into god knows where. After the boys, the walls thinned. And then Flannery O’Connor got her teeth into me. “Art,” she writes, requires a delicate adjustment of the outer and inner worlds in such a way that, without changing their nature, they can be seen through each other.” I wonder how delicate she was talking because when I write stories there is a leaking I never experienced writing poetry. There is a lot of two way peering. You know that disclaimer in the beginning of fiction? The one that goes: “This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.” Do you think we need to write this because part of us knows it isn’t entirely true? Are you afraid of hurting your children’s feelings? My son (age 4) told me he doesn’t like the title Wild Milk. He thinks milk should only be beautiful and warm. Never wild. He said this with great authority. He said he wished I called the book “And Everything Would Be Beautiful and Nice.” We hadn’t even opened the book and already I had hurt his feelings. Have your stories ever hurt someone’s feelings?

EM: Has my work ever hurt anyone’s feelings? In most ways I’m very soft-hearted but in this way, no. I don’t care. Perhaps I don’t care because if I started I would never stop caring. My children (who are older than yours) are remarkably bored by the fact that both of their parents are writers, and so I think your 4-year-old is a prodigy, already interested and already interpreting.

One of the things I most love about your work and Wild Milk is your brilliance with metaphor. Probably, deep down, the thing that matters to me most in writing is metaphor. Intellectually, I don’t think so—I’m interested in other things (also everywhere in Wild Milk): idiosyncratic imagination, strange worlds, character. But the thing that thrills me, without my permission or analysis, is metaphor. So I love the idea of digging out of the floor of a prose poem especially.

I want to ask you more about metaphor later. For now: how did these pieces arrive to you? First in language, or image, or scenario?

SOM: Bruno Schulz wrote how in childhood we arrive mysteriously at certain images “like filaments in a solution around which the sense of the world crystalizes… [and] establishes our soul’s fixed fund of capital.” I love this so much. He goes on to write that these “early images mark the boundaries of an artist’s creativity.” We are then left with a “single verse” that attaches itself to our souls by a knot that “grows tighter and tighter.” And we keep working at this knot like an ancient seamstress in an endless fairytale. I think my knot is made of dust, and mother, and that scene in Pinocchio when Geppetto (the color of snow or whipped cream) is dining by candlelight on live minnows in the belly of a shark, and pieces of the Hebrew alphabet, and the Holocaust, and the rabbi I never will be (I wish sometimes I was a rabbi), and a long, long joke with a punchline always seconds away from landing.

But you asked me how these pieces arrive, and I think first there is the knot that is always there. Then there is a word or a name. Like seahorse, or Bye Bye Francoise. Then there is this silence inside me that only gets volume once it goes through the doors of a story or poem. I am a shy person. I have a lot of silence. Maybe three or four extra helpings.

I wonder if the knot is what Faulkner referred to as the darlings we are supposed to kill. I never did like that advice: “Kill your darlings.” My son Noah has lost five teeth so far and I keep them all in a tin box with blue and yellow flowers. And when my grandfather died my mother gave me his sweater, and when I reached into the pocket there were breadcrumbs. Large ones. I have those in a box too. I am saving it all. The knot, the teeth, the breadcrumbs, the darlings, the whole shebang. One of the reasons I am so gaga over your writing is I feel that impulse too. One of my favorite passages on earth is in The Giant’s House that begins: “I’d lied, of course. Somebody did want the bones: me.”

You seem to want to keep your darlings. They morph and muse, but they return. Like falling. You have a lot of falling. That seems to be part of your knot (which I accidentally typed as “know”). Sudden falling. And you also have grief that instead of narrowing, widens and widens and widens your imaginative landscape. As if grief was soil where new language could grow.

EM: “Kill your darlings” is my least favorite piece of writing advice of all time. It feels like it comes from the past; when we were supposed to distrust idiosyncrasy. Another piece of advice that I hate: “Writing shouldn’t call attention to itself.” Well why on earth not, say I. I love writing that calls attention to itself. For me the sentences are the knot, the breadcrumbs, the milk teeth, the whole kit and kaboodle. Let’s talk fairytales: for years I’ve tried to write a version of Andersen’s The Snow Queen because I love the opening so much—who could not want to read something that starts, “Now then! We will begin. When the story is done you shall know a great deal more than you do know.” And also: perversely I want readers to feel the exact opposite when they finish something, I want them to feel as though they know less, but more interestingly.

Which is one of the things I love in Wild Milk. My head is full when I finish each story, but I’m less certain of nearly everything. Even names. Even whether you’ve made up your vast knowledge of snails or not.

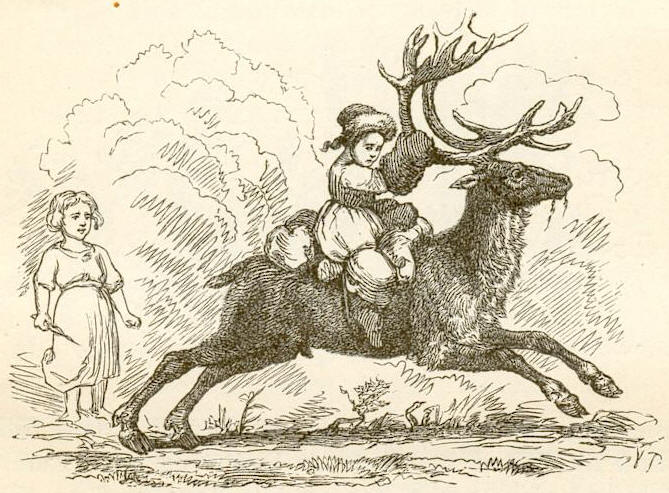

I’ll never write my version of The Snow Queen, I don’t think—so many other people have done it by now—which leaves me to think about it all the time, particularly the shards of glass that end up in hearts and eyes. It explains so much. What’s the fairy tale you can’t shake?

SOM: I love The Snow Queen, too. Especially the part when the glass breaks because the demon’s schoolchildren want to hold the mirror up to the angels (“the higher they flew the more slippery the glass became”). It reminds me of the Tower of Babel story. The curse for wanting to know the (real) name of god is babble. And the curse for wanting to know the ugliness of angels is GLASS IN YOUR HEART and the UGLINESS OF EVERYTHING.

Though it’s more folk than fairy, I am very obsessed with The Golem because no matter how much I’ve tried I can’t fully understand it. The moon-colored Golem made out of hebrew letters and clay comes alive when aleph mem tav (emet / truth) is traced on its forehead and the Golem protects the Jews of Prague and can see the future because he has no soul but then the Jews have a period of peace so the Golem spends entire days motionless in the corner of the synagogue then grows defiant (because he feels useless) until he catches the gaze of a small girl and stares at her with the pleasure of discovering the world for the first time but a rabbi tells her to erase the aleph (the Golem has been defiant) and so the girl erases the aleph on his forehead changing the word “truth” (emet) to death (met). And then the Golem dies. Amen?

My husband, for a birthday present, had an artist make two golems for me. Two little giants. I look at them and they look at me and we all shrug. Maybe your Snow Queen is my Golem. We should write both stories over. Until we know even less. And then even less.

Speaking of the Golem, I wanted to ask you something about truth and death. Something about how what creates the Golem is only one letter away from what erases him. Something about our proximity to the edges of ourselves, edges that feel like strangers. An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination is such a masterpiece because you seem to enter humor through terror, and the unreal through the real, and truth through death, and happiness through sorrow, and place (or belonging) through oblivion. I’m trying to ask you something, I think, about fiction and memoir, and how they seep into each other. You write, at the end, of time splitting in half, of “some back alley of the universe” where you took care of your first baby who was born stillborn, where our lives, our living, is “an exact replica of a figment of our imagination.” What am I asking? Maybe something about that back alley. Are we always, do you think, one letter away from there? Maybe that’s where all our stories come from?

EM: For somebody who doesn’t believe in an afterlife and who doesn’t understand anything about string theory or multiverses, I think all the time about The Fork in the Road, those moments you choose or life chooses for you, and you head off one direction. What happens to that other direction? I married late and had children late, and until I was 35 (and a half!) I was absolutely certain of the general direction my life was headed. It was a happy life, too. I would choose this one, every time, if offered the choice, but I sometimes wonder how the other direction would have worked out. In my work, too, I like to wander down the other fork in the road.

And I do also believe the opposites of things are always very close. There is no humor without death, and the consolation for death is black humor. Love and fury, the familiar and the strange, the delicious and the revolting. Yes, I think you’re right: all one letter off.