Museum where the exhibition is located: The Old Stone House; Museum cost of entry: nothing; Type of field near museum, according to website: “open synthetic turf field”; Adjective author used to describe field: bouncy; Revolutionary War battle that happened near museum: Battle of Brooklyn; Baseball team for which museum acted as a clubhouse: the Brooklyn Grays (predecessor to the Dodgers); Number of times that the author’s partner has corrected her that the baseball team wasn’t the Brooklyn Dodgers, but an early predecessor: many.

Central Question: How can a monument reflect the complications of history?

On the eastern edge of Park Slope, in the center of an enormous playground, sits a shoulder-high statue of Christopher Columbus. From a distance, the statue looks like it is carved out of stone or cast in cement, but closer examination reveals the figure to be spongy and porous—more vegetable than mineral. A haphazardly laminated label affixed to a nearby fencepost states that this statue is made of mycelium, a kind of fungus, and will eventually break down and transform into a patch of mushrooms. Behind the statue is an unassuming building that at first seems there only to house the public bathrooms. But it is, in fact, a historical museum called the Old Stone House.

The Columbus statue, made by artist Zaq Landsberg, is a miniature replica of a statue that stands nine miles away, atop a 28-foot rostral column in Columbus Circle. The mushroom statue is an outdoor element of a temporary exhibition at the Old Stone House called Race and Revolution: Reimagining Monuments, put together by independent curator Katie Fuller. The show is part of a series of exhibitions that Fuller has put together to explore patterns of systemic racism. Landsberg’s fungal facsimile is an effort to address the fraught history behind the uptown archetype original—a majestic representation of a man we now consider to be a genocidal monster. Yet the Columbus Circle monument itself was born from a noble impulse, sponsored by the Italian-American community in the late 19th century as a way to counter the systemic prejudice they faced as new immigrants. By creating a monument that is ephemeral—one that openly acknowledges that its use value may be limited; that its meaning may evolve, and its truth may be less than universal—Landsberg points to the changing nature of history. He asks the viewer to imagine historical monuments not as static and permanent, but as embodying shifting and sometimes contradictory ideas, undergoing growth and decay and, ultimately, disappearing.

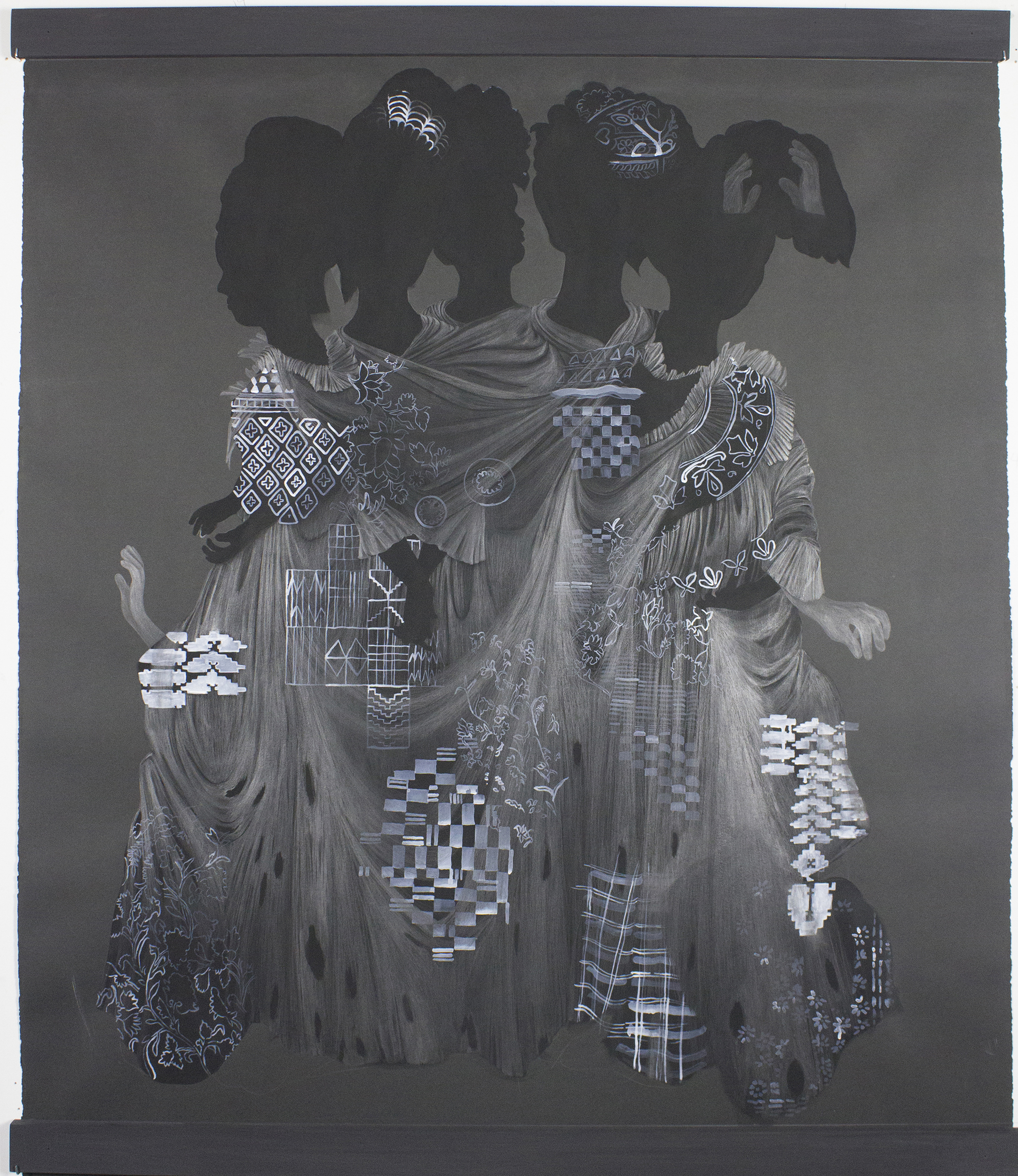

There are over 800 public monuments in the New York City, including 125 statues that honor historical figures. Only five of those statues represent women; only nine represent black people (two are of Jackie Robinson and one is of Harriet Tubman, the only representation of a black woman). The group exhibition at Old Stone House is meant to interrogate this inequity, featuring works that question the stories of the “Great White Men” cast in bronze and marble and affixed to plinths across the city. It also offers works that imagine beyond those men and suggest other people and events, that might be worthy of remembering and honoring, and how this might be accomplished. Each work on display provides a plan for a new monument, one that honors or mourns an overlooked hero or remembers a suppressed tragedy.

Contained primarily within the second floor of the cozy museum, the works in Race and Revolution seem to jump off the walls—the place is packed, cluttered with alternative ways to imagine the history of New York. There is a proposal to amend the Gay Liberation Monument, currently standing in front of the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street. The existing monument is made up of four white plaster figures—two men and two women—touching each other tamely, if not affectionately. Artist Sal Muñoz has blown up a photo of the monument and inserted images of people of color and gender nonconforming people throwing rocks in protest. There is both anger and joyfulness in their expressions; frustration and liberation. The additional figures stand in sharp contrast to the nervous white statues who seem afraid to offer each other more than a light caress, as if to not alarm or offend heterosexual passers-by. Muñoz’s artistic intervention provokes us to consider what we lose when we smooth out the edges of history, when we memorialize people holding hands, but not throwing rocks.

A piece by the feminist art collective “The Institute for Wishful Thinking” takes on the legacy of the so-called father of modern gynecology, J. Marion Sims, who, in the mid-19th century, conducted medical experiments without anesthesia on women who were enslaved. Until it was recently moved to Green-Wood Cemetery by the DeBlasio administration, there was for decades a large metal statue honoring Sims at the corner of 103rd Street and Fifth Avenue on the perimeter of Central Park. The Institute for Wishful Thinking has offered an alternative to the statue: in a shadow box, they have installed three speculums designed by Sims—including one that is nothing more than an enormous metal serving spoon—and engraved them with his words. “Introducing the bent handle of the spoon,” one says, “I saw what no man had ever seen.”

As a person with a vagina, I feel the aggression of Sim’s tools as they poke out of the box. I feel the callousness of his words. It is hard not to imagine the bulbous metal implements inside my body. Here a memorial becomes visceral, a place that call up the specificity of Sims’ callousness towards the women he claimed to be helping. We don’t see him as a handsome doctor with a giant mustache, we see him as the man whose hands held these specula and performed excruciating surgeries without permission or anesthetic on women who were powerless to refuse him.

There is a breathlessness to Race and Revolution, a feeling of there being almost too much to say, too many stories and histories to bring forward. The works take up every free corner of the space, almost overlapping each other on the walls. There are proposals for monuments and memorials to Biggie Smalls, Sandra Bland, the residents of the free black community of Seneca Village, before it was transformed into Central Park. There is documentation of a performance piece that questions why George Washington, who enslaved more than 250 people, continues to be venerated. There is a piece that addresses the slave market that existed for 150 years in downtown Manhattan and a piece that tells the story of a girl who was beaten and put in solitary confinement for saying fuck at a reform school in upstate New York.

I visited the show twice, and kept finding it difficult to know where to look, to focus in on any one thing for very long before feeling urgent in my need to see the next thing, to learn about another disregarded tragedy, another forgotten life. This show has taken on an almost impossible task. When you start to look for histories that haven’t been told, memorials that haven’t been built, you will find enough to fill every ally, park, and berm in the city. Taken as a whole, this exhibition gives some sense of what that alternative reality might feel like: full and layered, almost overwhelming in its tragedy, its grief, and feeling of possibility.

Leaving Old Stone House, I wonder what other histories surround me in this particular patch of Brooklyn. What if every historical event, every life transformed by history, was remembered and re-remembered? I can imagine a battle memorial and a memorial for the people being displaced by gentrification; a monument for the members of the Brooklyn Grays who played in the fields around the Old Stone House and a monument to Susan McKinney Steward, a black physician who ran a nearby hospital for sick children in the years after the Civil War. I imagine the mess of the past stacked up on top of itself in all of its strangeness and sadness, imploring the guys playing handball and the parents of the children on the jungle gyms to consider everything else that this park has been, everyone else who has walked on this ground.

Race and Revolution succeeds not because it is nuanced but because it is blunt. There are long labels that situate the work in historical context, there is no mistaking what stories the pieces are trying to tell. Many of the pieces are not just considerations of the past, but re-considerations, and are asking straightforward, clear questions. How do we think about Stonewall in 2019? What layer can we add to a statue of George Washington to properly situate him in history? The exhibit takes as its premise that a memorial can’t just be built and then left alone for all of posterity—none of the proposals here are for triumphal arches. Instead, a memorial must be in constant conversation with the present, asking not only what history once meant, but what it means now. If we build a statue to Columbus, this show says, let’s build it out of living, ephemeral, imperfect material and watch as it blooms grotesquely and then decays, leaving behind a fertile patch for remembering again and remembering more.