“Is it too late to make a space for yourself?”

How Michael DeForge describes himself:

Awkward

Angry but also non-confrontational

Extremely Canadian

Midway through Sticks Angelica, Folk Hero, Michael DeForge’s comic about a sturdy-legged nature enthusiast attempting to make a new home for herself in a Canadian national park, an intruder appears. He’s wearing a plaid flannel button-down and a baseball cap, and introduces himself as journalist Michael DeForge. “Do you have any response to the allegations that you were involved in your father’s election fraud?” he asks Sticks. She promptly jabs him in the chin and he goes down so hard he gets stuck in the ground for months, until his muscles and bones wither to nothing. Eventually, Sticks returns to dig him out and he floats away, his body a spindly wisp of skin. “This will be great for my career as a journalist,” he says. It isn’t—he ends up lonely on a hospital bed, his story scooped by a local bear, penning vindictive gossip in a magazine column titled “Forest Tattler.”

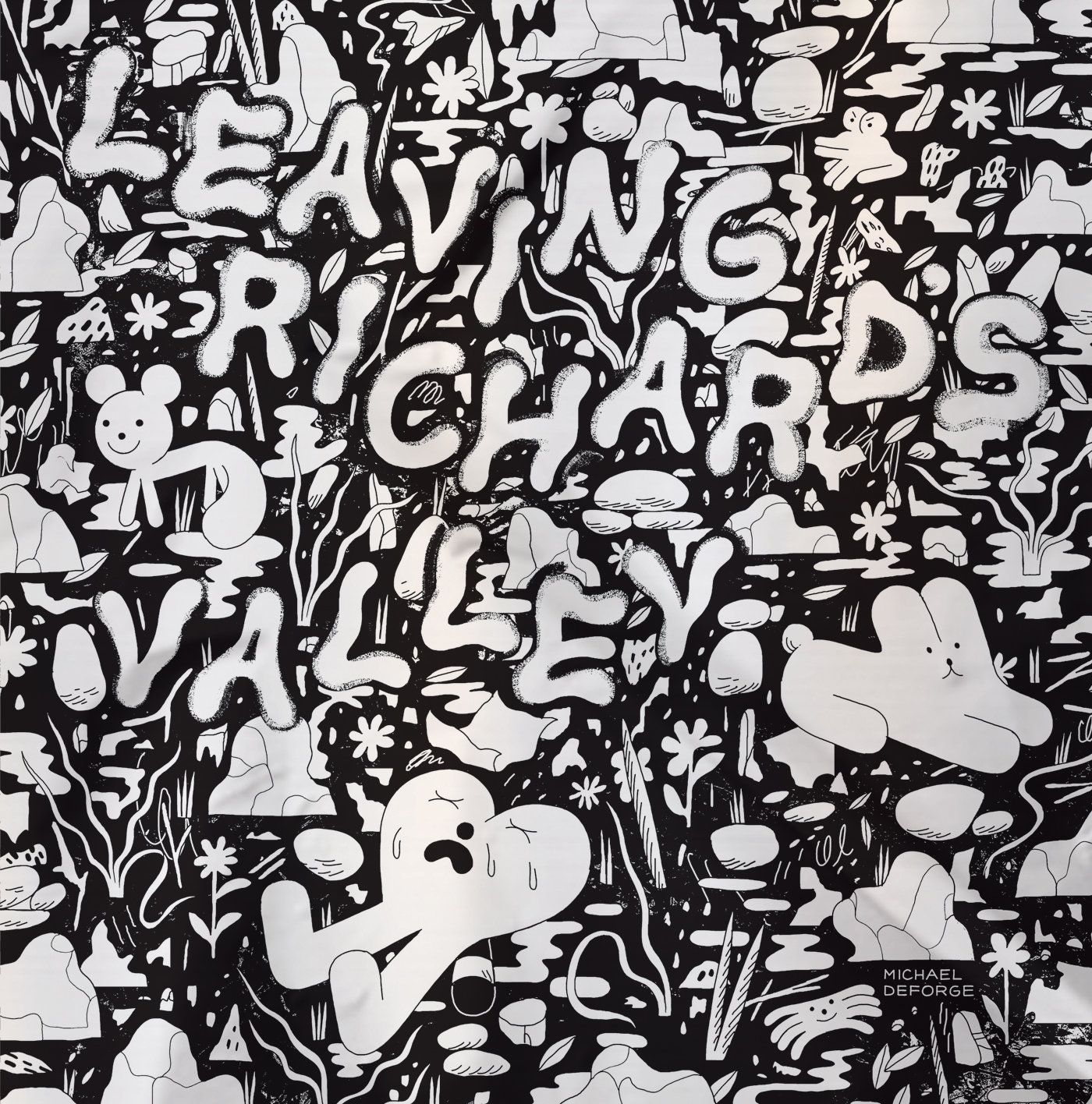

In real life DeForge, like many self-deprecating humorists, is unassuming and sincere. He has published ten books and worked as a designer on the Cartoon Network series Adventure Time. His drawings consist of simple lines, flat perspective, and a limited palette of bright colors, but the worlds therein are a profusion of organic shapes that suggest a richness of interior emotion. Many of DeForge’s stories rely on the highly specific personalities and neuroses of the characters: a depressive snake, say, or a frog with cutthroat artistic ambition, or a spider and a squirrel who pose together to make a celebrity named Julianne Napkin. Those characters appear in DeForge’s most recent book, Leaving Richard’s Valley, published in April. It returns to many of the same themes as Sticks; both books center on a community of forest animals devoted to an idealistic human leader. But while Sticks Angelica is admirable for her classically Canadian attributes—fitness, outdoor skills, no-nonsense equanimity—Richard’s obsession with purity and wellness starts to take on a tinge of madness as the story goes on. Then a small cohort of Richard’s animal devotees flee to urban Toronto to build their own utopia.

I met DeForge last month at Russ & Daughters Cafe, in New York City’s Lower East Side. While he sipped on a shrub soda, I asked him about the process of drawing a daily comic strip, his anarchic vision of Toronto, and the meaning of utopia.

—Camille Bromley

I. “I feel extremely Canadian.”

THE BELIEVER: Leaving Richard’s Valley was first published on Instagram as a daily comic. Why did you decide to do that?

MICHAEL DEFORGE: I had been wanting to do a daily comic for a really long time. I’d done weekly strips and I enjoyed the process of serialization, but I knew a daily strip would be a bigger time commitment. I wasn’t sure if I could handle it. But then my day job ended. I had been working as a designer for a cartoon for six years and change, and when it ended I wasn’t sure what the texture of my day was going to look like. I thought it was as good a time as any to try the daily strip thing.

BLVR: Were you drawing and publishing each comic every day, or were you drafting a bunch in advance?

MDF: I would only do it one day in advance. I would sometimes backlog them if I was going to travel, or if I knew I was going to have a lot of commercial deadlines or something. What I wanted was to be put on the spot on a daily basis. I like being forced to improvise.

BLVR: Did you give yourself a time limit?

MDF: Not really. Usually it would work out that I would start at the beginning of the afternoon and finish at four or five. But it really depended on the strip. Sometimes it would only take an hour. Reading through, it’s probably clear which ones didn’t take very long at all. There are stretches where it’s just the characters speaking in front of a background. The claymation week took a lot more effort because I was making everything out of Plasticene. It was something I hadn’t done before and I had a lot of false starts.

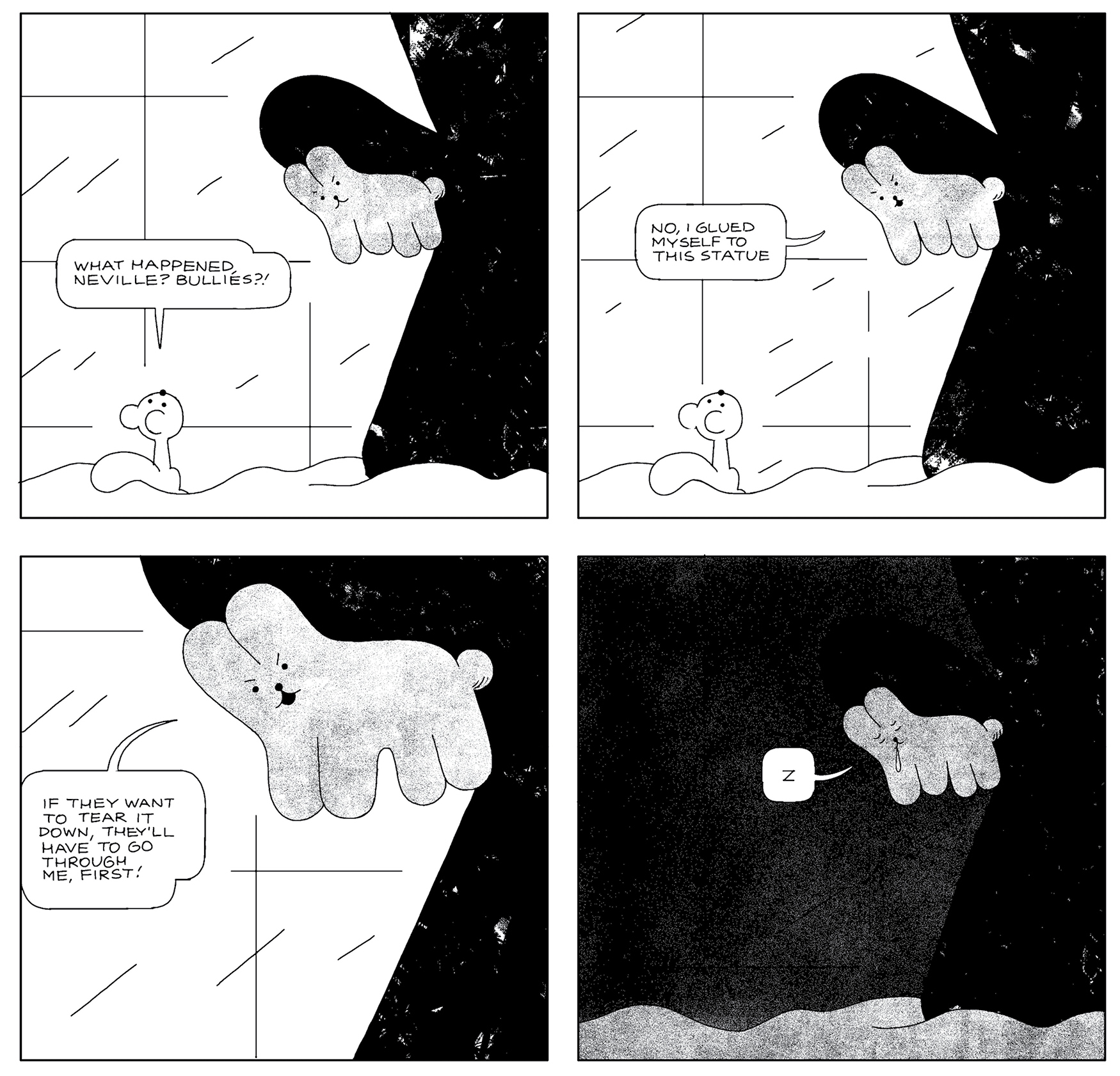

BLVR: I noticed that the styles in the book change: there is some claymation and some Xeroxed-looking backgrounds.

MDF: In general I wanted to be flexible with the style. It’s a mix of photo collage—photos I took around Toronto—and then scanned photocopy textures. I tend to have a very sterile, clean line and I wanted this comic to look different. I wanted it to reflect the way Toronto actually feels to me. So the collage and textural elements were trying to evoke a very particular visual noise and clutter that are specific to Toronto. People talk about cities being dirty and grimy generally, but Toronto is cluttered in a specific way. Our storefronts are very noisy. A classic Toronto storefront is decorated where you’ll see thirty different plants, and then someone’s weird collection of candles, and then a stack of magazines that go back decades, and then the store itself will be an optometrist’s or something completely unrelated. Toronto is also filled with debris to the point where you have manmade islands of discarded construction material and bricks.

BLVR: What version of Toronto were you trying to create in this book?

MDF: A lot of it is specific to my experience of Toronto—I’ve lived there twelve or thirteen years now. But I folded in current events and current buildings. I also tried to pay tribute to aspects of Toronto history, to reference and evoke Toronto’s actual history of communes and art spaces. There’s a statue in the book that is a tribute to a real statue in Toronto called the Unknown Student. It’s on a busy street close to the University of Toronto and next to a convenience store, and it was originally produced by a famous old hippie school called Rochdale College, a free school that eventually was shut down for drug activity. Rochdale has a big legacy with a lot of notable people from the art scene. Coach House Press printed out of there. A sexual health clinic called the Hassle Free Clinic started out of Rochdale. I tried to pay direct visual tribute in the book, or at least evoke the spirit of Rochdale.

BLVR: What attracts you to stories of alternative communities?

MDF: It’s instructive, and in the case of Rochdale, sometimes inspiring. It’s hard to imagine a way out of the current hole we’re in, and part of that work requires looking at the histories of other people who’ve tried to find an alternative, and looking at the ways they succeeded and the ways that they failed.

BLVR: I noticed that on the cover of Sticks Angelica, you put a little Canadian flag next to your name. How self-consciously do you identify as a Canadian?

MDF: I feel extremely Canadian.

BLVR: What traits make one extremely Canadian?

MDF: Probably the inability to ever determine what being Canadian ever really means. Canadians are always undergoing some sort of identity crisis, partially because that lack of definition comes part and parcel with any settler colonial state, but also because we tend to always define ourselves in relation to Britain or the United States.

BLVR: The utopias you describe in Leaving Richard’s Valley and Sticks Angelica are both populated with animals and set in parks. Is being in the outdoors important to you? Do you go camping or hiking?

MDF: I’ve never been camping in my life. I’m not very outdoorsy, and I’ve always lived in cities. Part of the gag with Sticks Angelica was that the central character starts out the book actually being a little inept at living in the wild because she had been a city-dweller for so long. Many Canadians feel this affinity towards nature, even the ones who’ve lived in cities their entire lives and would probably die if they spent five minutes alone in a forest.

II. “I like pink and it’s safe.”

BLVR: I felt that Leaving Richard’s Valley could be described as a dystopian version of Sticks Angelica. There are these two seemingly benevolent cultish leaders who are adored by their animal companions. They’re both living in a sort of Eden but then the story zooms out and you realize that the utopia is just a public park. And they’re both obsessed with health and wellness. How much of this was intentional?

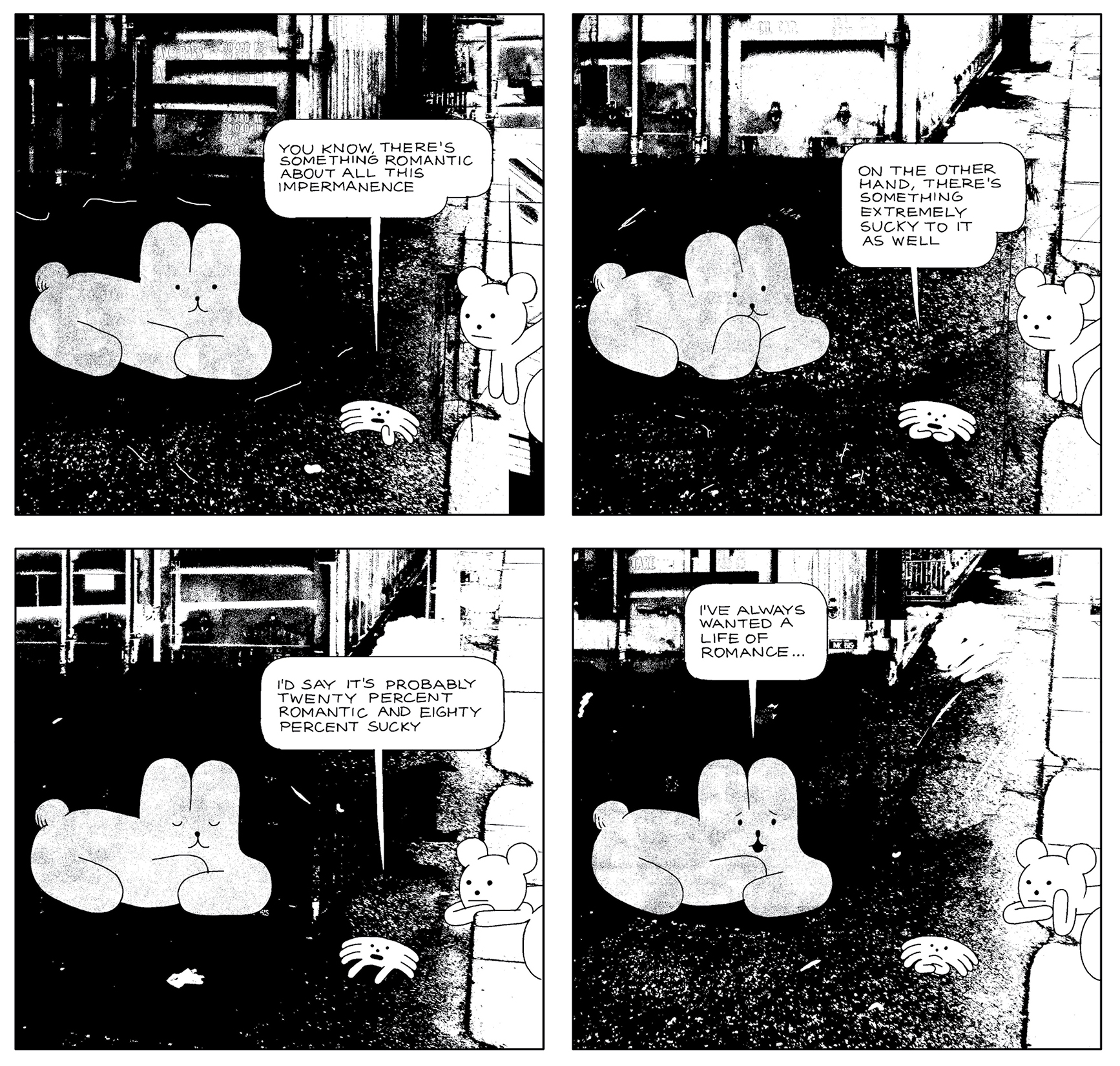

MDF: They’re themes that I end up circling back to. I’ve been trying to write more about communities starting something new and sometimes failing or having mixed success. I see both comics as being about that: building these new communities together and seeing if they can do it, especially within the city where you’re under siege so often. Seeing whether that’s even possible.

BLVR: But you seem to be ridiculing the effort.

MDF: I don’t mean to ridicule it. Certainly I don’t want the cult to be the thing I’m admiring in Leaving Richard’s Valley but the characters’ efforts post-exile, in the city—that’s what I see as being what the comic is about. Seeing if they can build and live in some art space. I feel like my work was so preoccupied with dystopia for so long that I do want to write about groups of people, or animals I guess, seeing what alternatives might be feasible. A lot of Leaving Richard’s Valley is about whether it’s too late for cities. Whether they really are just these dystopian hellholes and we’re just totally at the whims of capital and all fucked. I still live in a city so I don’t want to believe that. But I don’t know if it’s too late. That was the central question with Leaving Richard’s Valley: Is it too late to make a space for yourself?

BLVR: What does utopia mean to you? What would it look like?

MDF: I’m not totally sure what it would or should look like, which I think is why my stories try to present a bunch of different options. We want to work towards a world without capitalism, without police, without borders—but I think most of us would be fooling ourselves if we said we could picture exactly what that the shape of that is going to be. Because it’s a world we haven’t built yet.

BLVR: It’s interesting that you say that your work is preoccupied with dystopia, because to me your colors communicate the opposite. When I think of your work I see bright candy colors like pink and yellow.

MDF: I do tend to go to loud colors. I like swapping between black-and-white projects and color projects, I think because they end up being extreme contrasts. A lot of my sense of color came from me starting out in poster making. When I was in high school I would silkscreen gig posters. That was how I cut my teeth. It taught me a lot about color theory because I was limited by the amount of ink I could by and I’d have to mix them. I would use a lot of loud colors because they look good on a poster. So I stuck with it.

BLVR: Your color combination in Sticks Angelica in particular is really striking: white, black, and pink. You were limited to only three colors, which I imagine must be hard.

MDF: For Sticks it was almost an afterthought. I knew I didn’t want the comic to be full color but black, white, and gray looked too drab. I picked a soft pink because I like pink and it’s safe. It was an impulsive choice that ended up working. I could have easily picked a color that I would have gotten sick of.

BLVR: Now it’s hard to imagine that book not in that color.

MDF: Yeah, it’s like trying to imagine Ghost World not in light blue.

BLVR: Everyone comments on how your animal characters don’t look much like animals. How do you design them?

MDF: I just go with my first impulse, knowing it will sort itself out. The difference between how characters look on page one of Leaving Richard’s Valley is pretty different from the way they look at the end. I’ve become okay with the fact that the way I draw characters will change over the course of a hundred pages. They start out kind of skinny and become puffier. I’m also very attracted to awkward-looking characters. I feel awkward in my own body and so I like building characters a little impractically. At this point it’s hard to talk about the process because it just works out. I just draw it.

BLVR: Is this a purposeful decision, a way for you to actively work out personal feelings? Or is it sort of an inevitability in the story-making?

MDF: Yeah, I think that’s just inevitable, but I’m much more aware of it now than I was when I first started.

BLVR: Do you have a rough story in mind from the start? Or do you go panel by panel?

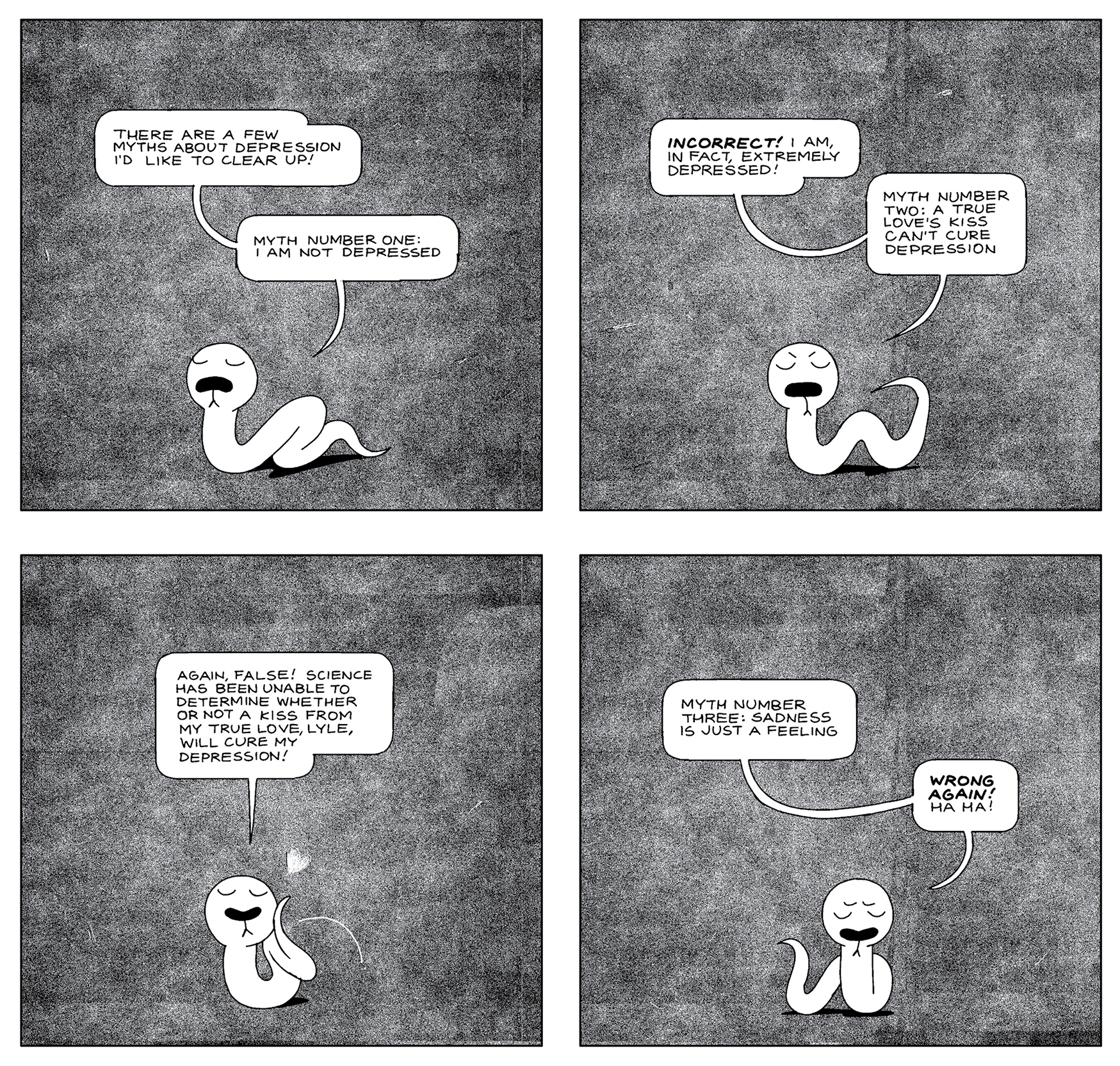

MDF: I go strip by strip. I try not to plot out too much in advance. For Richard’s Valley I knew it was going to be about this group getting exiled from a cult, and that it would take place in Toronto. But I tried to not plot out too much more than that. If I stick too close to something it can feel limiting. I’ll have a few key personalities when I start but I like letting myself be surprised by characters. Caroline the Frog and Snake Mark, for example. I really didn’t have any plans for them, but they became my two favorite characters to write. Lyle started out as the central character but he’s tedious, depressive, and angry, and that can be kind of limiting. I didn’t know that starting out. But Mark and Caroline, I could take them all these different places.

BLVR: Does the finished book reflect the Instagram postings day by day?

MDF: Yeah. The only changes were typos.

BLVR: Speaking as an editor whose job it is to think about structure and narrative, it’s surprising that the finished book feels so balanced and coherent. I could imagine you taking a long thread in one direction before realizing it wasn’t going anywhere and then dropping it and doing something else.

MDF: Since I’ve collected a few strips now—Ant Colony and Sticks Angelica were done the same way—I just have to trust that it will flow okay in a book. Or just be okay with it not flowing, because that’s the nature of any strip. A lot of that is just crossing your fingers.

BLVR: Did people’s responses to the comic on Instagram—their comments or how many people liked it—influence where you took the story?

MDF: I really enjoyed being able to read the comments in real time. That was fun and novel for me. The only way it changed the way I wrote was in the character Caroline. When she was first introduced everyone hated her. But I really liked drawing her, and I felt a sort of affection for her. I thought, I want to get people on board with this character. Or at least I wanted to subject them to her more. I was a little egged on by how intensely people disliked that character, and I wanted to explore her more because of that.

BLVR: I like that her creative genius is motivated by rage.

MDF: She’s a lot of things I wish I could be.

BLVR: You’re not motivated by rage?

MDF: I feel a rage, but I don’t feel like I get to act on it that much. I’m classically Canadian in that I’m extremely angry but also non-confrontational. Which is the worst of both worlds.

III. “In comics you can fudge a little.”

BLVR: This is a broad question, but go with your gut. What makes a comic good?

MDF: When I’m reading other people’s work, it will be if I find myself thinking about it a week later. The immediate feeling after finishing something is less important than what sticks with me later. After the first experience is gone, what makes it good is the thing I still found upsetting about it, or the joke I’m still laughing at.

BLVR: Without naming specific artists, what influences you?

MDF: I like looking at an artist’s body of work and seeing them address the same themes over and over again from slightly different vantage points. I like to think I’m doing that with my own work: the feeling that you’re chiseling away at something and the final thing isn’t going to be clear until you’re dead, or maybe not even then. Long ago I realized that I’m just hashing out a lot of the same ideas. Lately it’s been about communities and attempts at utopias. And specific traumas from my own life will constantly repeat themselves in my work. I admire that in other artists. Whenever I feel like I’m making any progress, it’s that feeling that I’m chipping away at something. I like to imagine one day it seeming clearer to me, this thing that I’m working on.

BLVR: Do you watch animated shows?

MDF: I keep up with a few. Like everything Lisa Hanawalt is doing.

BLVR: Bojack Horseman?

MDF: Yeah. I’m very excited for the new one.

BLVR: It’s also full of animals. And there’s a moose named Lisa Hanawalt in Sticks Angelica. Is she a good friend of yours?

MDF: That is true. She’s a friend, but I initially was designing this character who was a moose dressed as a human, and this thing happened when I was drawing it where I thought, I can’t draw a moose wearing human clothing without it just looking like a Lisa Hanawalt drawing. I thought I would make that influence as explicit as possible. So I asked her, “Hey would it be cool if I named this character after you?”

BLVR: I’m curious about your work on Adventure Time. Other than it being a satisfying day job, what did you learn there that influenced your own work?

MDF: I’d never had anyone correcting or critiquing my work before.

BLVR: You didn’t go to art school?

MDF: No. I really valued that in this case because it was just about pure drawing technique. It made me a more elegant cartoonist. The head designers and art directors I worked under would mark up my drawing and it’d be really clear: I took twelve lines to communicate something that I could have done in three lines. That was very helpful. You also can’t cheat as much in animation. For my job, when I was told, “Hey draw this car engine,” I had to learn how to draw a car engine. But in comics you can fudge a little. If you don’t feel like drawing a character’s feet you just don’t include it. For the nature of an animated show grounded in time and space in a specific way, you can’t get away with things quite as much.

BLVR: What do you get away with in your own comics?

MDF: Oh, I’ll cut out entire scenes or characters if I’m finding them too annoying to draw. I hate having to draw cars properly, so I don’t bother anymore, and make them all children’s drawings of cars. Little hats, or whatever.