In front of my North Oakland home my car’s sat idle and dusty for two months. There’s nowhere to go with it: the bookstores that I frequent are shut, some for good; bars I’d normally wander into on a weekend night on the assurance of seeing friends are closed; same goes for the cafes that tolerate my using them as makeshift offices. I no longer drive to Cal’s campus in Berkeley to teach. Instead, in the mornings I go for coffee, meandering through the residential streets to the east of San Pablo Avenue until I hit Alcatraz.

The walks are lovely. My feet carry me past roses and perennials and California poppies blooming in my neighbors’ front yards. Pretty pastel painted houses glisten in the discordant spring sun. Trees ranging from ubiquitous Blue Elderberries to Persian Silk Blossoms to Shreve Oaks provide shade and cast shadows out of a Baroque canvas. The effect is a kaleidoscopic riot of color and light that can leave you wondering if you’ve ever really seen color and light before. People wave from their front porches, happy to see anyone who isn’t a family member or roommate. I stroll past community gardens tucked away into the tight labyrinthine streets around Temescal Creek, and those tiny libraries that never have anything I want to read but are still cute to look at. On San Pablo I have discovered the services of not one but two psychics. One of them has adapted to the pandemic by letting people leave questions in a mailbox; I left one a few weeks ago but have yet to receive a response.

I’m not alone on these mornings. The pandemic has turned my neighborhood’s sidewalks, once just sparsely trafficked urban formalities, into public forums. Suddenly neighbors who a few months ago were mere notions hiding behind gentrifences and renovated facades are everywhere, jogging and admiring the flowers and talking with far off friends. We nod and smile at one another; sometimes we even stop to talk, projecting our voices so we can be heard from six feet away. Sometimes there are so many people trying to use a sidewalk that we have to step off them into the streets to maintain distance, but we do so smiling. There’s one couple I see every morning, and again walking past my kitchen window every evening. The husband walks with a small baby strapped to his chest while the wife struggles with a dog straining against its leash. I had never seen them before April but have since figured out that they live three houses down from me.

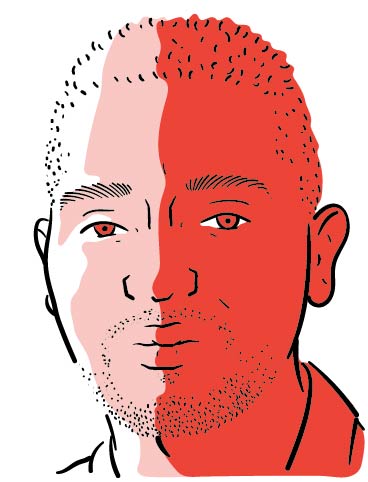

Even though walking through North Oakland can feel like walking through a postcard vision of California, I’ve come to feel uneasy about it over the last few weeks. Last week, despite everything in my body that told me not to, I watched the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s killing. Ever since I have had to wonder whose pristine vision I’ve been walking through. California is not Georgia; Oakland is not Satilla Shores. There are no lessons to be drawn from Arbery’s murder at the hands of Travis and Gregory McMichael that we have not already learned and that we will not keep learning again and again. The murder was a sobering reminder to me, though, that we cannot talk about public space in America without thinking about how race creates that space; and that I cannot experience that space without thinking about how race shadows my experience.

After all, it’s no coincidence that I don’t know most of my neighbors, even those living nearest to me. Like most of the Bay, the neighborhoods of North Oakland have undergone frenzied change over the last eight years I’ve lived here. My house sits on the border between two neighborhoods, Gaskill to the east and Golden Gate to the west. Directly to the north of me Paradise Park sits at Oakland’s theoretical border with Berkeley, invisible aside from a garish public sculpture on Adeline Street that declares Berkeley “HERE” and Oakland “THERE.” Emeryville, a tiny city that consists mostly of big box stores, a mall, the Pixar campus, and a strip mall with a Wing Stop I am too familiar with, is nestled to the southwest of me. The area is a nest of single-family-home neighborhoods that boast bungalows, Victorians and Craftsmen, some blessed Spanish Colonial charmers, and those newly constructed modern boxes that are, sadly, the homes of Oakland’s future. Because this is California there are also apartment complexes that run the gamut from Le Corbusier-inspired futurism to wannabe Italian villas. Developers, real estate websites, and gentrifiers call this urban knot “NOBE,” a hideous acronym that means “North Oakland, Berkeley, and Emeryville.”

The NOBE coinage was already in circulation on all the Craigslist ads I saw while looking for housing in the summer of 2012. Its usage coincided with a 2010 gang injunction that then-Oakland mayor Jean Quan imposed on fifty-five black men whom authorities identified as part of the North Side Oakland gang. The injunction prohibited these men from, among other things, walking in public with one another. In addition it imposed a 10 p.m. curfew on all listed individuals. The injunction amounted to an interdiction on black men’s sociality. I don’t dispute the existence or danger of gang activity in the area—deadly gun violence was too common in the first few years of my time in North Oakland—but I do wonder at the coincidence between gentrification’s early stages and the injunction. I recognized it from my former life in Los Angeles’ Venice Beach. In the early-aughts, increased LAPD activity in the black Oakwood district happened to arrive with eager white homebuyers unnerved by what had theretofore been normal public life: people playing dominoes and drinking in Oakwood Park, congregating in alleys for innocent and, yeah, sometimes illegal activity, or playing music without regard to the hour. Suddenly cops were everywhere, clearing black residents for the surge of capital.

Oakwood is a very different place now. The public activities that defined black social life in the area were largely snuffed out as Venice began to boast multimillion-dollar two-bedroom bungalows. Its black population tumbled. I’ve recognized the same pattern in North Oakland, where most of the neighbors who welcomed me when I arrived are gone, flung out to Richmond or Vallejo, and even as far as Sacramento. Their replacements have been white professionals. The city eventually dropped the injunction in 2015, but by that year North Oakland was transformed. Last year, the family who lived across the street from me was evicted. The landlord tossed their belongings into a dumpster that sat out front their house, and a “For Sale” sign went up. A few months later the house was painted a cool shade of blue; a man moved in with his pregnant wife and Prius. There was a year when four of my neighbors disappeared in this manner.

There was so much rhetoric in the pandemic’s early days about COVID-19 being a great equalizer of experience, in that race does not determine the virus’ ability to infect people. We now know that rhetoric to be false: black and Latinx citizens are overwhelmingly more likely to be infected by the virus, not because of anything biological, but because the virus’ fallout has followed the contours of existing racial inequalities. Meanwhile, black people who wear masks in public—as they are required to do in all of California, for example—are in danger of police harassment, even as cops are also abusing them for not wearing masks or socially distancing. I’m not sure the pandemic has fundamentally altered anything about American space’s racial underpinnings, so much as brought those underpinnings into view.

So it’s hard for me, now, not to think of myself as enjoying the repercussions of this two-pronged process. The pretty renovated facades of my neighbors’ houses, their sylvan gardens, even the cute little libraries—I can’t reduce my pleasure to a process, but I can’t exclude them from it either. My lush walks mark me as a lucky benefactor of a process of which I might become an eventual target. One day last week, wandering south of my house, I took Philip Roth’s Indignation out of a tiny library, happy to have found something I actually wanted, and promised to come back with another title. At that moment an OPD patrol car came down the block and just happened to slow down when it neared me. The lone officer made eye contact, said nothing. A second or two later he sped onward. I don’t think that I cut a particularly menacing figure that day, in my Birkenstocks and dad jeans and oversized sweatshirt; I also know that doesn’t matter. It’s not my vision that I’m walking through.