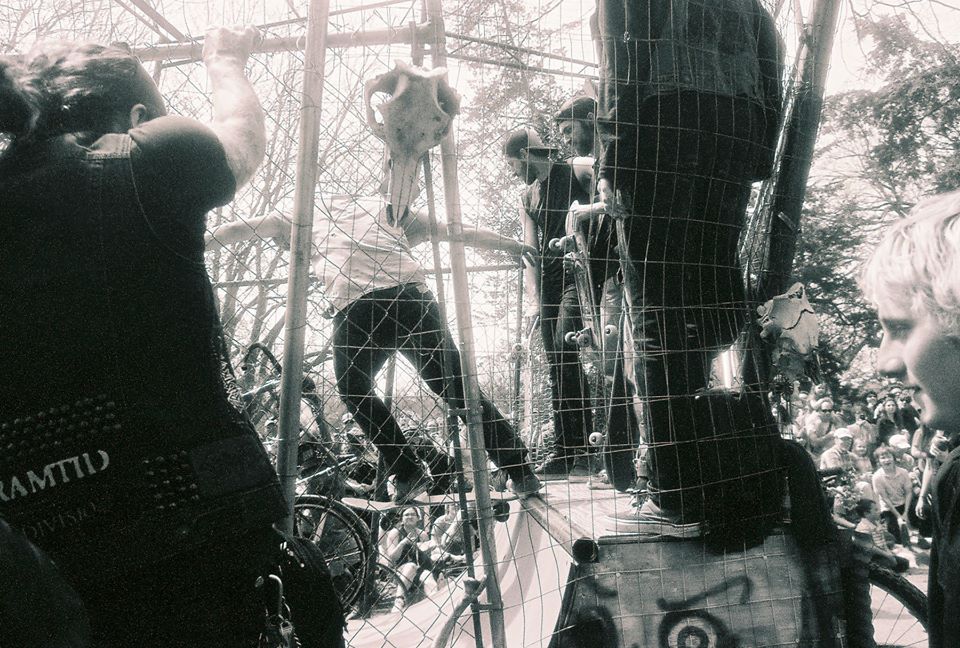

I live in South Minneapolis, where I grew up, in a galaxy of communities, punk houses, home recording studios, apartments I used to live in—where I’m less than a mile from my high school, the first house my father owned, just a block from the church that held the first funeral I ever attended for a friend. Powderhorn, the park at the geographic and cultural crossroads of the Southside, is just a few blocks east of where I now live. It’s just as lively as it ever is in May, probably more so since the virus hit; some days, it’s almost alarming how many people are out. But I’m there, too. I mostly skate the tennis courts at night, where the nets were recently put back up, the gates unlocked; where, during the stay-at-home order, I sanitized my hands after hopping the fence, before opening a beer. More dedicated skaters might not feel this way, but I always liked skating because it made me feel less in my body. The speed and muscle memory of balance gives a sense of weightlessness, where walking, by comparison, feels clumsy and awkward, the frustration of my body’s limitations showing up in each subsequent step. Skating the courts holds so much of the disorienting atmosphere of “these times”: Everything is so bad—how is it that, for a moment, everything can feel so normal?

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in