“If families didn’t break apart, I suppose there’d be no need for art.”

Things Loudon Wainwright III Doesn’t Do:

Conceal experience

Play music every day

Know what it all means

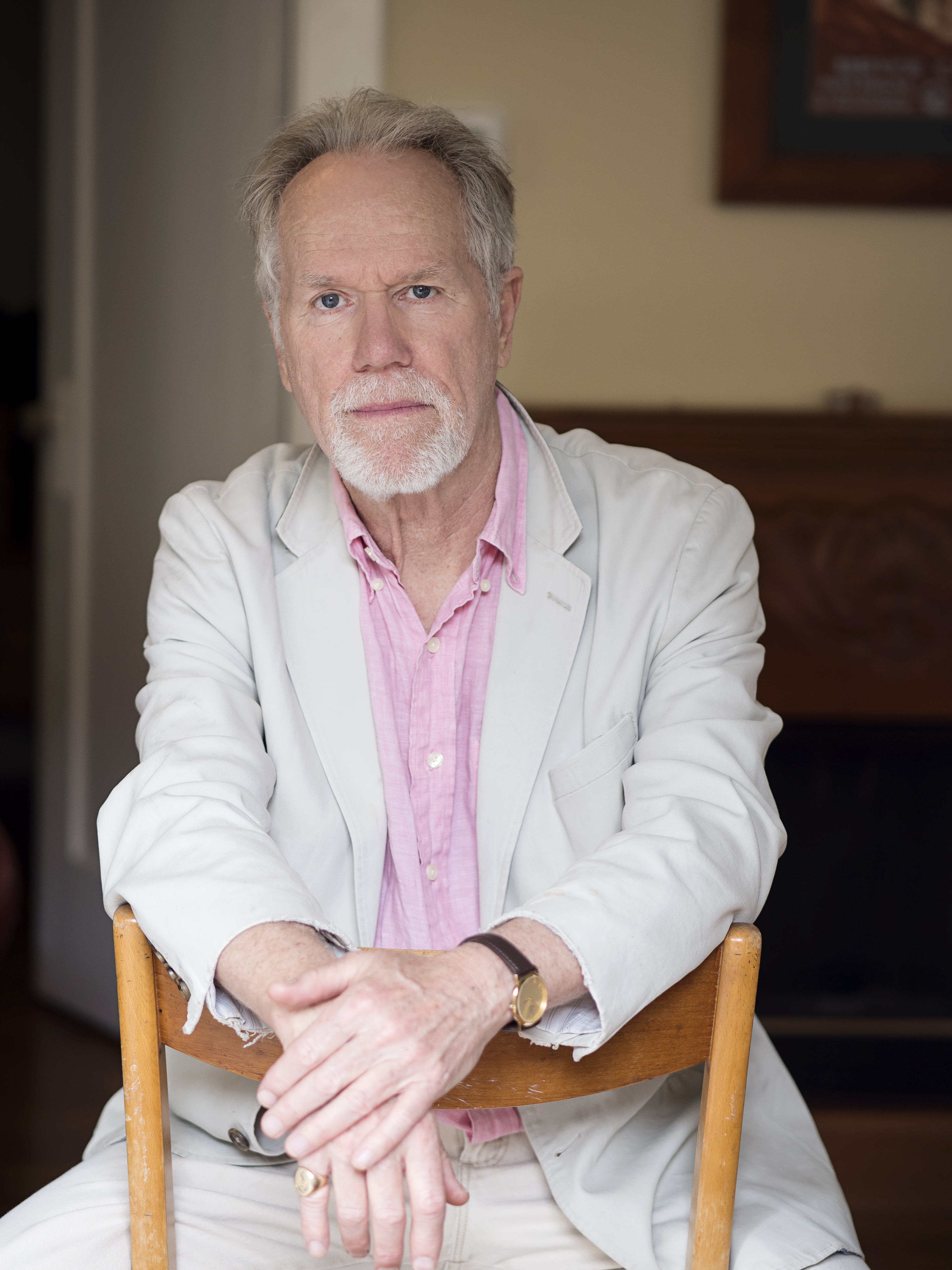

It’s fifty years since Loudon Wainwright III—son of the exemplary Life magazine columnist, Loudon Wainwright Jr.—began writing and recording his songs—fifty years of astounding music, fifty years of bleak passages and struggle, fifty years of confessional lyrics on a scale few have attempted, fifty years of openly failing the women and children in his life, fifty years of black humor, great rhymes, despair, and full-on entertainment, fifty years of (most often) standing in a club by himself with an acoustic guitar. As befits such a moment, Loudon Wainwright III has been involved in a great many retrospective projects recently. The first of these was last year’s autobiographical literary opus, Liner Notes (Blue Rider Press), which dishes some serious dirt about the dead, and which is also full of excoriations and painful truths about the author himself. The second of these retrospective projects is a brand new collection of rarities, Years In the Making, b-sides, lo-fi recordings, a cappella rants, organized into suites, like “Kids” and “Love Hurts,” which find a hindsight-is-twenty-twenty poignancy in the Wainwright songbook even when tragicomic truth-telling is the order of the day. And the third project, just released on Netflix (and directed by the redoubtable auteur Christopher Guest), is a film of a show he has been doing on the road for a few years now, Surviving Twin, in which Wainwright both reads from his father’s columns and performs songs that collide with the biographical facts of his father’s life, as well as that of Loudon’s own celebrated son, songwriter Rufus Wainwright.

That’s a lot of retrospective work for a guy in his seventies. Wainwright, less acerbic in person than in some of his work, seems somewhat at peace with the retrospection, the somewhat here being, perhaps, a lifelong qualifier, likewise with the well-known ups and downs of his life now, and happy to take pleasure in the work of his extended family, as well as his own capacity to continue to entertain. I have been keen to interview Wainwright since I first saw him perform some twenty years ago, at Bennington College, in a barn, where the very literary songs of the guy with the solo guitar played extremely well, and after which Wainwright came to hang out and chat with David Gates, Sven Birkerts, and Amy Hempel. A memorable night. Some songwriters, in addition to excelling at their craft, make a profound virtue out of surviving. They become an entertainer everyone...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in