Warning: spoilers abound, and all victorious feelings of conclusion may be compromised.

Non-Exhaustive List of Television Shows Mentioned:

Melrose Place (1992-1997)

Seinfeld (1989-1998)

Six Feet Under (2001-2005)

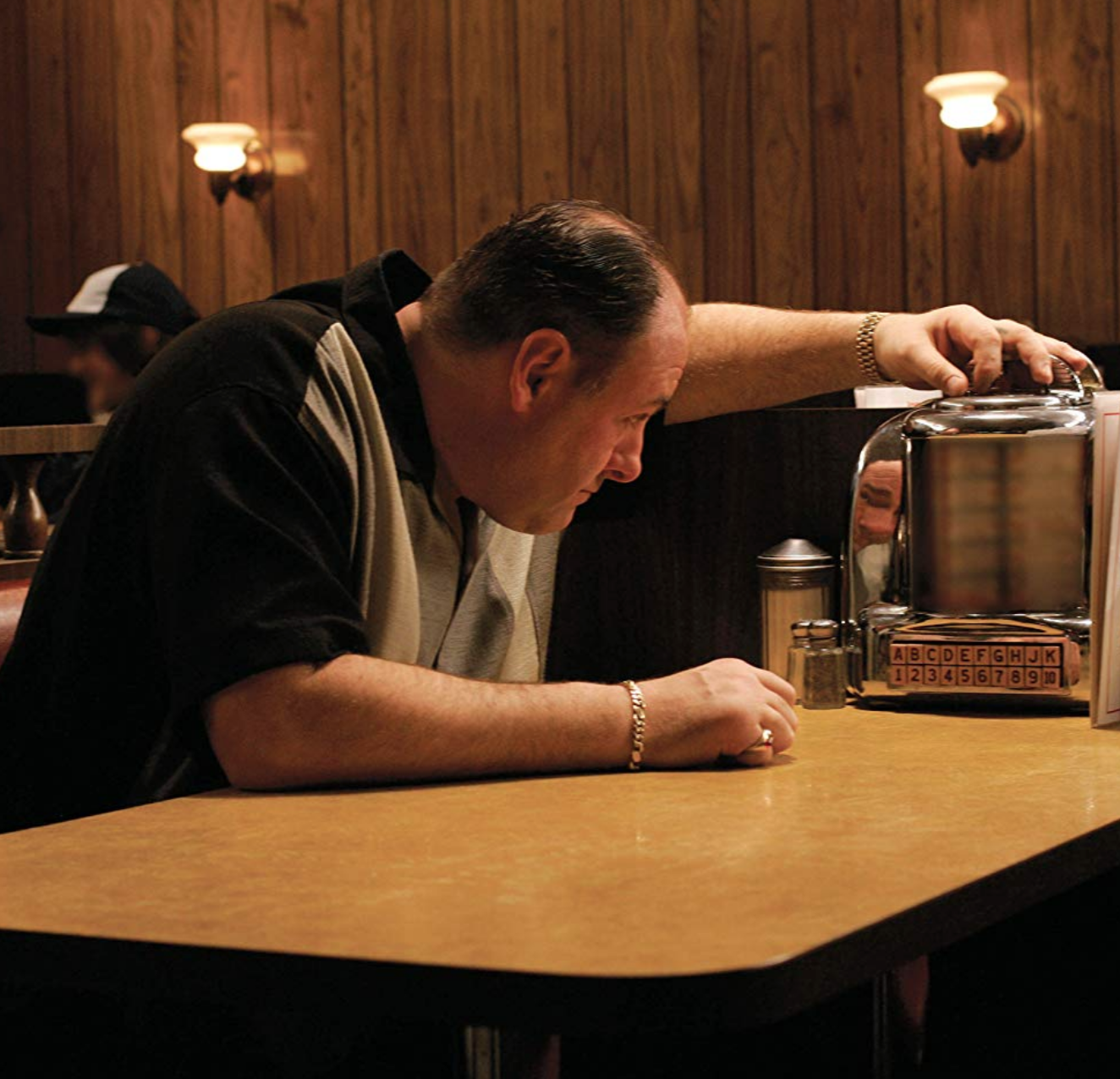

The Sopranos (1999-2007)

Lamb Chop’s Sing-Along (1992-1995)

On May 24, 1998, in its thirty-five episode-long seventh season, Melrose Place ended with the series finale “Asses to Ashes.” It’s a doozy of an episode that encapsulates the mood of the entire show—slamming murder confessions, embezzlement investigations, cadavers, left-for-dead characters (two of them) in bathtubs, a pregnancy with surprise paternity results, arrests, an attempted murder, and a funeral into one hour with four commercial breaks. The show—which followed an evolving cast of (mostly white) beefcake basics with zero interpersonal skills or healthy boundaries—ends with Peter Burns (played by Jack Wagner)—who supposedly was dead but now isn’t, thanks to all of the above elaborate ruses—and Heather Locklear’s iconic Amanda Woodward tying the knot on some nondescript Southern Californian beach. The song playing as they walked off into the sunset for all eternity? Semisonic’s 1998 sleeper hit, “Closing Time”:

Closing time

Time for you to go back to the places you will be from.

Closing time

This room won’t be open ’til your brothers or you sisters come.

So gather up your jackets, and move it to the exits

I hope you have found a

Friend.

…

Closing time

Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end.

Of the song, Semisonic lead singer Dan Wilson says the lyrics both describe his baby’s birth and “being born” in genere. Appropriately, just as Melrose Place spun off from hunky carpenter Jake Hanson’s (played by Grant Show) appearance on the quintessential primetime teen soap 90210, it too beget Models, Inc.—the doomed program with a single-season run starring Locklear’s character’s mother. If, as “Closing Time” states, every beginning is, in actuality, an ending, were all seven seasons of Melrose Place a gestational period? It’s an on-the-nose choice in musical accompaniment, but then again, no one has ever accused Melrose Place of subtlety. The song is both comfort for those mourning the loss of these characters they’d followed for years, and a hint toward other replacement shows in the pipeline that they could swallow their grief, if they waited until sweep season.

The idiom, “swan song,” refers to an archaic belief that swans break their lifelong silences to intone a bittersweet yet poignant song at the moment of their deaths. The term’s source is disputed but written references date back to third century Greece, in texts by Aeschylus, Plato, and Socrates,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in