David Lynch’s seldom-seen short, “How Now Brown Cow?” begins with an industrial din of clanks and genitalia-tightening screeches punctuated by the occasional shriek of an unseen bovine. The entire screen fills with smoke that appears to be exuded by an antique radio with no dial, positioned on a Formica table beside a (gradually visible) phantom in a kind of modified welder’s helmet that renders the figure featureless. He is seated in a lawn chair, dressed in a designer Thom Browne suit and a butcher’s apron that drips with a viscous black liquid. From behind the camera, a guest clomps into focus: a retro-sexy woman aloft on full-body crutches that give a great clatter as she finally finds a seat before the butcher.

The butcher finally speaks in a halting, cornfed Jimmy Stewart accent, “Have you cast a shadow lately?”

“What… is… this?” the woman stutters, “The… farmer… in… the… dell?”

“Old McDonald had a farm,” says the butcher.

“He… fell… into… his… own… thresher,” the woman replies.

A conveyor belt next to the butcher stirs to life and carries a miniature, poorly-CGI’d cow to the butcher. Once sliced, the cow deflates with a fartsome alarum. The short ends with the butcher removing his helmet to reveal Lynch himself, his famously curvilinear hairdo somehow intact, and we cut to black while “Duke of Earl” as sung by Johnny Casino and the Gamblers plays over the credits for no reason. Where’s Angelo Badalamenti when you need him?

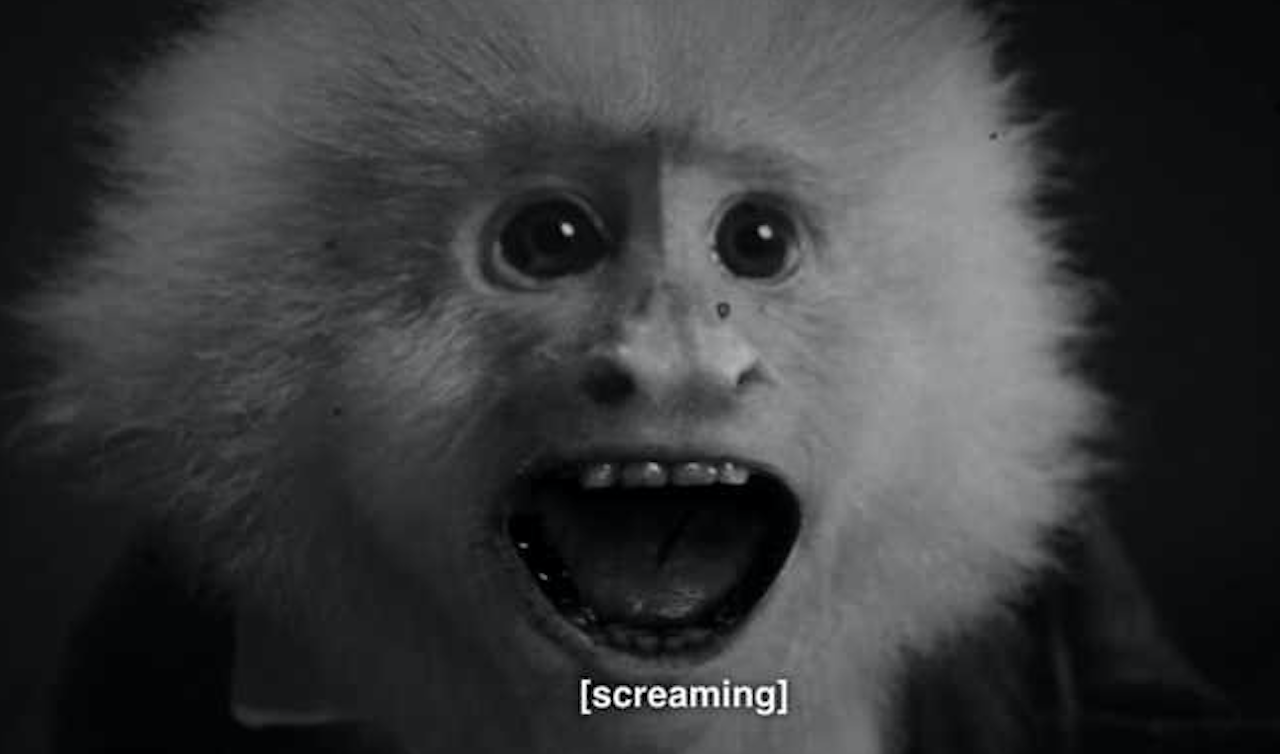

I’m just kidding. “How Now Brown Cow?” isn’t a real David Lynch movie, but it might as well be, considering how interchangeable and indifferent the output of the once-untouchable maestro behind Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks has become. There is only one way to be normal—that’s why it’s called normal—but a million ways to be weird, and in the course of his long career, David Lynch has developed a style, or rather a set of rules, characterized by violence, menace, and non-sequitur, all firmly positioned under the banner of a weirdness that regularly frustrates the same urge toward interpretation that it stimulates. Lynch can lay claim to a surprisingly broad appeal that makes me think of Thomas Pynchon’s famous observation that “Every weirdo in the world is on my wavelength.” Lynch could say the same. But what’s weird without unconformity, without deviation, joy, and upset? Now more product than director, Lynch’s tropes are immediately recognizable: physical deformity, buzzing electricity, extremely hot women, rockabilly tunes, and twisted Americana, not to mention having done for chessboard-pattern foyers and red curtains what Tim Burton did for striped socks. Oh, and everyone smokes. If hipsters printed their own currency, Lynch would...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in