“Edge Cases” is a new series from The Believer featuring short interviews with artists and creatives who work with technology.

For years I’ve followed Colorado-based research scientist Janelle Shane’s adventures with artificial intelligence on Twitter and her aptly titled blog AI Weirdness. Working with everything from My Little Pony names to cookie recipes to knitting designs, Janelle dissects and explains how neural networks and algorithms actually work, all while generating the absurd and humorous. Her new book You Look Like A Thing And I Love You: How AI Works And Why It’s Making The World A Weirder Place was released this past November.

—Maxwell Neely-Cohen

THE BELIEVER: How would you describe what you do to a kindergarten class?

What I do is I use computers to write really weird interesting things. I give the computer something that it’s supposed to try to copy, but because this computer program can’t really understand what it is I’ve given it, it tends to make mistakes as it’s trying to figure out what is going on. But the mistakes are often really funny and interesting, and give me a window into how this computer sees the world, what a program knows and definitely does not know. So the mistakes are actually the fun part. They’re what I look for and they are where I find the stories.

I trained a neural network on 1,228 types of cookies and apparently these are what cookies sound like to it.https://t.co/YS8vbgWiyz pic.twitter.com/ommtYtAMAs

— Janelle Shane (@JanelleCShane) December 7, 2018

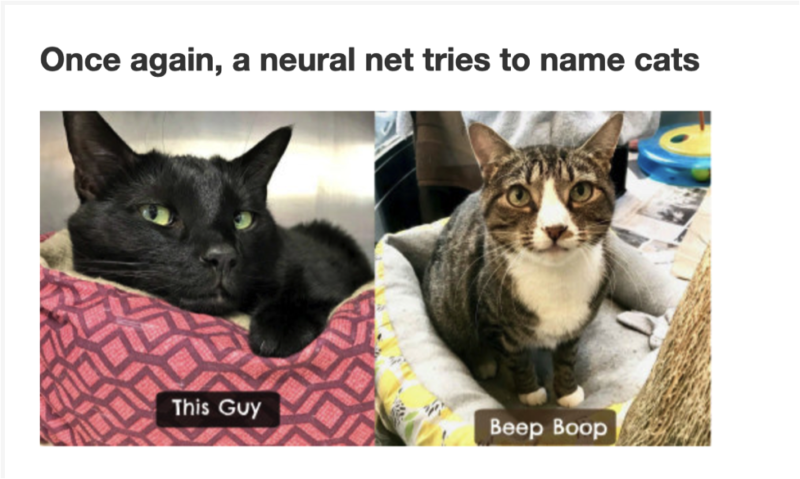

BLVR: This is just me going from memory, but you’ve trained neural networks on Recipes, Cocktails, Pies, naming Cats, Pick Up Lines, cookies, first sentences of novels, to name a few. Do you have favorites?

JS: You know my favorite ones are the ones that end up engaging a community of creative humans in some way. Most recently that was the Inktober prompts. If you’re not familiar, in October artist Jake Parker puts out a list of drawing prompts, and artists all over the world do a drawing a day. So I generated some really weird ones with AI and then I just posted them on my blog, and then discovered so many people who had never heard of me before were drawing them. They are fantastic, weird, funny, otherworldly, disturbing. It was amazing to see what all the different interpretations they could have of the phrase “take control of ostrich” for example, or “two block squishy”.

SkyKnit: when knitters teamed up with a neural networkhttps://t.co/HMDkMF7Te1 pic.twitter.com/wd2F9J9Glh

— Janelle Shane (@JanelleCShane) April 19, 2018

Another experiment that had that broader effect was SkyKnit, or the HAT 3000 crochet projects. My own contribution was only a part of what it ended up being, because there’s so many talented people who took these bare bones and applied their own creativity to it, and produced these amazing works off of it.

I trained a neural net to generate crochet hat patterns, and they showed a disturbing tendency to explode into ruffled hyperbolic yarn-eating brain shapes.https://t.co/9tu6mJOStv

image credit: Chunky Hat, crocheted by Joannastar. More in the linked thread. https://t.co/Icii4ymd9X pic.twitter.com/hVOGNXcwNM

— Janelle Shane (@JanelleCShane) September 4, 2019

BLVR: What do you think made you approach AI from a place of humor, of being interested in really weird funny AI, and what motivated you to start to writing about it?

JS: At first I was definitely mainly writing this up just for me with no expectations that anyone else would necessarily read it. It was purely, what about this do I find cool what about this do I want to remember and document for myself?

It is so immediately humorous. It was the humorous application that grabbed me. If you’re sitting at a computer barely able to breathe because you’re laughing so hard that tears are streaming down your face, that’s a sign that something has really grabbed you.

BLVR: It’s interesting to me that as soon as the knowledge and tools became available to easily train neural networks, humans immediately started using them to create things that are funny or ridiculous. I’m interested in what this says about AI, but also what this says about us. Why do you think we have this temptation to use these tools for silly things? Why are these things so good at making things which are hilarious?

JS: All of its hilarity comes from mistakes that it makes. Mistakes that a human would not make, and so that can be a lot of fun. It reflects the world back to us in this absurdly distorted way. And it’s also safe to make fun of as well. AI doesn’t care if you make fun of its grammar or its lack of understanding for how the world works. That’s another way in which AI humor is this particularly attractive thing.

BLVR: I’m curious what the transition was like from publishing work on twitter and on your blog, and actually turning it into a book. How did that change the way you think and work?

JS: Fortunately I did a PhD so the book isn’t the longest thing I have written. But still for me the book was a journey in self-confidence.

I started out being asked to write a book by an agent and publishers who had read my blog, and I thought, gosh me? What? Write a book? Like what would I write? What would this even be? Somewhere along the way I realized, ok it needs to be a book about AI, a general book about AI. Uhhhhh. Do I know enough about AI? I think this is what it needs to be but who am I to write this?

Eventually I understood what I meant to explain and meant to write, and realized having a general view of what’s going on, rather than very specific depth into a few different areas, can be an advantage.

I have heard from people in the field who do AI research or data science who say “you got this exactly right” and I have heard from people who say “my 12 year old, my 10 year old loves it” That was what I set out to do, but at the beginning of this process didn’t think was possible.

BLVR: There’s a tremendous incentive in business and technology to automate, to optimize, one thing your book does very effectively is show that it isn’t always that simple, that whether its too broad a dataset or something like catastrophic forgetting or giraffing, there are potential pitfalls everywhere. I’m curious if you’ve learned anything about why is it so hard for us to balance convenience or advantage with danger? Not to make you solve the world’s problems with a single question…

JS: AI shows itself to be a tool, like so many of the tools we pick up, where there are good ways to use it and there are harmful ways to use it. And we are seeing this full range of possibilities with AI just like so many other human endeavors.

It’s a little bit different in that I think in the past we haven’t had people saying “ oh yes well don’t worry, we’ll train the fire to be ethical.” Whereas you sometimes you get that from people talking about AI. “Oh yeah, don’t worry, it can harm us if we train it to be ethical.” Or “Oh no what if it decides humans are bad and it needs to take action!”

AI, like fire, does not have an internal directive to kill the humans or whatever, it just does what it does, for good or evil. I think it’s kind of interesting with AI there’s this perception that it is different. And that is where the intersection with science fiction becomes really interesting and complicated for AI as a field in particular.

BLVR: Maybe this is just something I’ve noticed, whether it’s predictive policing or YouTube’s recommendation algorithm leading to radicalization, do you feel that to some degree the public has a better idea of the downsides of a lot of AI systems and algorithms? Like it’s no longer just some Sci-Fi fear of Skynet, but an understanding that bias, mistakes, incentives for bad actors, all these are baked into these systems?

JS: I think it’s definitely getting better and I think there’s a lot of people who are doing good work to raise awareness of what algorithmic bias is for example. But there’s definitely a lot of work to be done, and I’m hoping my book is going to be a tool in that fight, to help spread some AI and algorithmic literacy. Because I do encounter people all the time still, who read my work and say “oh thank you I was so afraid of Skynet and now I realize…”

The Skynet thing is definitely still alive in people’s imaginations. And I’m not sure if we took a poll of whatever slice of the general public we wanted to make, whether more people have the Skynet view or the more realistic view. And that brings me back to this idea of interplay with science fiction. Because, I think science fiction has had so much of a history with AI that it’s this strange situation where more people are familiar with the science fiction version of AI than the actual version of AI.

BlVR: What can making art with AI teach us about AI? I’ve certainly found that making art with a technology enhances my understanding of it. I’m curious about the artistic and creative side of what you do and how that connects to the technological and communicative side of what you do.

JS: Yeah, especially with this text based sort of art with AI, it really highlights how much the final product still depends on human creativity and a human artist shaping everything. Coming up with the idea requires human input, taking the output and figuring out what to do with it also requires human input. Or figuring out what do you once you have a trained model, and how do you turn that into something that’s going to be interesting to read and have a story behind it.

Because scrolling through a list of a hundred thousand different generated paint colors for example or generated names of cookies—they’re not very readable by themselves. It is boring to just look at a dump of these sorts of things. When I’m showing stuff on my blog, I’m only picking one out of maybe a hundred things to show, and then I’m putting them in a very specific order so that I can have something interesting to say about them. It really does highlight how the output of the algorithm itself is boring, and it takes human creativity to make it more interesting.