At the beginning of The Crow (1994), a rock star named Eric Draven and his fiancé are attacked in their apartment and killed. The shots that make up this sequence are edited quickly, with rotating camera angles and flashing lighting effects that were in vogue in Hollywood during the late 80s and early 90s. In most of these shots, Eric is faceless, shown with his back turned or features obscured by his long black hair. When he is dragged to the window, shot, and thrown, we see only the guns pointed at him, his silhouette, and the various faces of the gang until he crashes through the glass. As he falls, the audience gets a good look at his face: blood trails from the broken bridge of his nose, there’s a cut on his forehead. The actor is Brandon Lee who, as you might already know, was dead when this scene was filmed.

A series of mistakes on set resulted in live propellent and a cartridge being inserted into the gun used for the attack scene. Lee was shot in the abdomen at point blank range. After his death, the producers decided that rewrites and reshoots would commence with the consent of his family. Chad Stahelski, Lee’s stunt double, was used as a body double for these scenes.

Body doubles in film have been common since Hollywood’s early days. Stunt performers, like Stahelski, are perhaps the most well-known type, chosen for their passing physical similarity to the primary actor. Perhaps the most recognizable yet simultaneously unknown double is Marli Renfro, Janet Leigh’s stand-in for the infamous shower murder scene in Psycho. They’re also used as copies, like when Linda Hamilton’s identical twin, Leslie, was employed for a scene in Terminator 2: Judgment Day where two Sarah Connors come face-to-face with one another. Nowadays, twins aren’t necessary if you need an exact copy. You just need a computer.

Digital technology has become so ubiquitous and sophisticated in the realm of film and TV production that there is hardly a project that isn’t somehow touched by it. But in the early 90s era of The Crow, the concept of replacing someone’s face without the use of makeup or prosthetics was groundbreaking. The technique had only been used a handful of times before. For instance, in a movie where almost no one noticed: Jurassic Park. When Ariana Richards’ Lex is hanging from the roof with raptors nipping at her toes and she looks up in terror at the camera, her face is a digital composite stitched onto her stunt double.

The Crow was different. Instead of just using Stahelski as a stand-in for Brandon Lee’s body, they also used his face. When Eric Draven falls to his death, you see two people at once: both Stahelski and Lee composited onto him. When Eric awakens from the dead, returns to his ransacked home, and sees himself in the mirror, he punches the glass so that it shatters. Lee’s face was digitally composited into the shards of glass left hanging in the mirror. And when the titular crow perches on Eric’s shoulder, the same technique was used. Lee’s face appears in the brief flashes of lightning that illuminate the apartment, but this is also Stahelski beneath the mask.

The Crow is notable for its seemingly altruistic intentions in reviving Brandon Lee to complete the film. This was received as moving homage rather than greedy ass-covering. Comparisons to The Crow were raised most recently in the wake of Paul Walker’s death by car accident during the production of Furious 7. In order to finish a few minor scenes, Walker’s two brothers, Caleb and Cody Walker, were used as stand-ins with digital face replacement. Reception to this was once again overwhelmingly positive, critically and generally. Fans were moved by the family’s involvement, while the brothers themselves noted how cathartic it was to be involved in an area of Paul’s life that they didn’t necessarily hear about. In an interview with Entertainment Tonight, Caleb said, “Paul kept a lot of things about work kind of quiet with his family and friends, and so we were able to learn some things through his co-stars.”

But the use of body doubles, particularly in the wake of an actor’s death, are not always commended by audiences. The Star Wars franchise knows this well. After Carrie Fisher died in late 2016, questions were immediately raised as to how LucasFilm and Disney were going to handle the following installment, in which Fisher was scheduled to appear. Mark Hamill said Fisher was “irreplaceable” as Princess Leia and online petitions for Meryl Streep to take over the role were vehemently opposed by fans. LucasFilm assured fans that it had no plans to digitally recreate Carrie Fisher’s performance. But in the Star Wars spin-off Rogue One, released just eleven days before Fisher’s death, a digital recreation of Peter Cushing was used to revive the character General Tarkin from the original trilogy, even though Cushing had been dead for over twenty years.

The double need not be a whole body: we have hand doubles, leg doubles, butt doubles, hair doubles, the notorious “stunt cock.” There are body doubles for nude scenes and death scenes and just about anything you’d feel is replaceable.

But within this industry of replicated bodies and parts, there can only be one star. One Tom Cruise, one Tom Hanks, one Will Smith, one Vin Diesel. In our worship of star power, we’re returning to the Golden Age of Hollywood, consolidating clout and popularity into a select few names. Whispers of Dwayne Johnson’s involvement in a film can make or break production. Studios are becoming more reliant on the prestige of their actors, particularly their faces. Where stunt doubles were once filmed from a distance, as in any number of action scenes from films like Point Break and Die Hard, it has become standard practice to paint out their faces and paste on the likeness of the lead.

Actors often run into the many folds and wrinkles of authenticity for a given role, especially when a character has to demonstrate physical prowess or transformation. (Remember skeletal Christian Bale playing an emaciated insomniac in The Machinist? Portly Christian Bale as Dick Cheney in Vice?) Increasingly, films assert the “real-life” skills of their actors. Ryan Gosling’s piano-playing skills are exhaustively displayed in La La Land, where sweeping, unbroken camera movements shoulder away any notion that he isn’t actually the person playing. Somehow the audience seems to find the performance more credible if the character’s skills are also those of the actor.

But it is the double’s job to provide the real skill and expertise, to help the audience suspend disbelief. Christopher Reeves as Superman didn’t actually fly. But you did see him do it.

To someone who is famous for eschewing the use of doubles like, say, Tom Cruise, there is no difference between suspension and authenticity. To him, the audience doesn’t just see Ethan Hunt scale a building and believe it; the audience believes because it knows that Ethan Hunt is really Tom Cruise. The logic, for Cruise, is simple: his body has to be on the line, in every shot, in every take. This is the emphasis for his most dangerous (and profitable) enterprises, particularly with Mission: Impossible. Cruise has achieved the kind of alchemy between celebrity and performance, like the Rock’s charisma combined with his infinitely increasing muscle mass, that enables him to maintain a tight grip on the distance between character and self. Every Tom Cruise movie takes place in a world that necessitates that only Tom Cruise can get the job done. He makes his presence necessary. He can’t ever disappear, or else the thrilling world we’ve paid to see him in for nearly forty years does too.

A double is necessary as well, except their role stands in the shadow of recognition. If we hold fast to the notion that movies are magic tricks, with elaborate scaffolding put in place to help you believe what unfolds before your very eyes, doubles are the sleight of hand on the road to a reveal that never comes. You see them, they disappear, they don’t come back.

Orson Welles’ final film, F For Fake, begins with a magic trick.

Welles begins by saying, “Ladies and gentlemen… this is a film about trickery, fraud, about lies. Tell it by the fireside or in a marketplace or in a movie, almost any story is almost certainly some kind of lie. But not this time. This is a promise. For the next hour, everything you hear from us is really true and based on solid fact.”

The film turns out to be a strange pseudo-documentary. Welles recounts the histories of a number of forgeries, artists, and history-makers who are all responsible for some form of deception. He quotes French magicians, follows journalists covering the legacies of the rich and famous, even introduces a never-before-heard story about a series of unknown Picasso paintings. He questions the notion of authenticity, of art that is verified and therefore truthful, whether the truth of anything can be declared official if it has been stamped and signed.

Then you realize, of course, that F for Fake’s runtime is well over an hour, that the promised honest hour has long since passed. Welles confesses he’s been “lying his head off” for the last seventeen minutes or so, including the bit about Picasso’s lost paintings. “Art, Picasso said, is a lie; a lie that makes us realize the truth. To the memory of that great man who will never cease to exist, I offer my apologies and wish you all, true and false, a very pleasant good evening.”

The enterprise of make-believe that Hollywood employs -in our case, doubles- may strike some as an erroneous observation. Movies are fake. They’re structures made real and tangible by the very fact that they exist as people, places, and events that might one day erode with the film or circuit they’re embedded on. They’re constructed out of simulations, sets made of plaster and plywood and light, that will only exist in the mind, long after what’s captured on camera has been broken down and sold off for parts. Nothing that’s so transient can be taken seriously. Only serious things really exist. But here is the part where, yes, I ask what it means for something to be “fake.”

As editor and film essayist Tony Zhou points out, what’s captured on camera is “always pretending to be somewhere else.” In Zhou’s case, he’s talking about Vancouver, and how it is almost never shot as Vancouver. But Mumbai? Seattle? Sure. It can look like New York City or Hong Kong or Pyongyang if you need it to. Every city, every person is made up of the same parts, pushed and pulled by the same gravity. Keira Knightley looks similar enough to Natalie Portman (see The Phantom Menace). Someone says nothing is original, another says nothing is real.

What is actually happening when someone scoffs after watching a movie and mutters “They didn’t really do that?” Of course they didn’t really do that. Are they simply saying that the movie was poorly made? That it’s audacious to play make-believe? No matter how preposterous the end result, films and images of any kind are made by real people in real places, with names and histories and corresponding levels of significance on the ladder toward recognition. This seems to holds most true when the studio resurrects you before the movie is even finished, Paul Walker, brother, or not.

Someone wants to question authenticity and what makes something “real” or not, one of the oldest conversations there is to have about art. The problem is the language is inadequate. We’re not speaking tangibly, we’re speaking emotionally. Fake is claiming fact for fiction, claiming that what you see is all that there is. Nothing ever truly happens spontaneously, nothing is generic. But it is made to feel that way. You need tools for it to work. Sometimes you need multiple.

Hollywood has a hard time agreeing with the idea that it takes more than stars to pull off a success.

In early 2011, after the 83rd Academy Awards, Wendy Perron, dancer and then-editor-in-chief of Dance Magazine, blogged about a dancer named Sarah Lane. Lane had performed as Natalie Portman’s dance double in Black Swan and Portman had just won an Oscar for her performance. In her acceptance speech, Portman thanks nearly every person she worked with on the film, including costume designers and the choreographer, but made no mention of Lane, nor the possibility that Portman did not perform every piece of ballet shown in the film. Furthermore, Lane is simply credited as the “Lady in the Lane” for a small cameo she has, and then again in a list under “Stunts.” These were omissions of significance to Perron.

In 2008, two years before the release of Black Swan, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button applied the same face-swapping technology, with none of the controversy attached. Brad Pitt, talented as he may be, couldn’t be physically shrunk down as his character aged backward. The production opted to digitally remove the faces of the performers playing Benjamin at his oldest stages with Pitt’s. “Lop their heads off,” as director David Fincher said. Seven performers portrayed Benjamin throughout the film. Three of their faces were replaced. All were credited as playing Benjamin.

In the run-up to Black Swan’s release, director Darren Aronofsky told USA Today of Portman’s dancing, “She was able to pull it off. Except for the wide shots when she has to be en pointe for a real long time, it’s Natalie on screen.” Sarah Lane herself attested to the actress’s achievement: “She worked really hard.” Mila Kunis, the co-star, echoed the same sentiment. “Natalie danced her ass off. I think it’s unfortunate that this is coming out and taking attention away from the praise Natalie deserved and got,” she said. The idea being: there is no one who works harder at anything than Natalie Portman. But Lane merely asked to be fairly credited for her work, not to detract recognition from the lead.

Aronofsky and Portman deem the final product to be the only truth that matters in the end. As long as you believe Sarah Lane’s body was Natalie Portman’s, you ostensibly know all you need to about how whatever you’re watching got up on screen. But there is not only one truth. Nothing arrives simply by being conjured. The sleight-of-hand is the diversion, from here to there, the motion that blurs single and double, Lane and Portman, and back again.

By the end of it all, Sarah Lane reaffirmed her initial intentions by saying that she didn’t regret taking part in the film, she just wanted recognition for the work she did. Portman stated merely that she was “really proud of everyone’s work on the movie and of my experience,” and that she didn’t want to get caught in the gossip and “nastiness.”

No one made quite the same fuss over two other dancers, Abby Nelson and Kimberly Prosa, who also doubled as the Black Swan.

A double is no less real than the actor they’re being fused with on camera. Or, if you like, they are no more fake than the character they are helping to create with someone else. To be physically similar to an actor who is also not being themselves, to be aesthetically congruent with somewhere half a world away, and to present them as one thing is not what makes a piece fake.

We haven’t even talked about the ethical concerns presented by the possibility of digital face replacement. Who owns the rights to your face? Peter Cushing’s estate had to give LucasFilm permission to use his likeness in Rogue One. In some instances, actors come in for 3D scanning sessions of their bodies and faces during production without explanation. And what if you don’t have an estate? More to the point, what if somebody just doesn’t care? With the advent of AI-based programs that can “deepfake” the combined existing images and video clips of a public figure into a photoreal avatar of their face, there is a precedent far beyond the bounds of entertainment for why these technologies, and the people who are used and erased by them, matter.

Frankly, digital face replacement doesn’t make a whole lot of sense if your argument is that audiences will be thrown out of the experience of watching a film otherwise. When seeing I, Tonya for the first time, I turned to my friend during a scene where “Margot Robbie” is supposed to be performing an impossible feat of figure skating, and said, “That is definitely not her.” They didn’t notice. Bad CGI or close physical resemblance amount to the same effect, and one doesn’t involve literal erasure.

The focus of the scene should have been on the character of Tonya Harding, which multiple people were necessary to play, not Margot Robbie as stunt double with Margot Robbie’s face as Tonya Harding. Nothing is going to take away from Robbie’s acting. That’s why she was hired. As were the athletes and performers who were tasked with accomplishing the things she couldn’t.

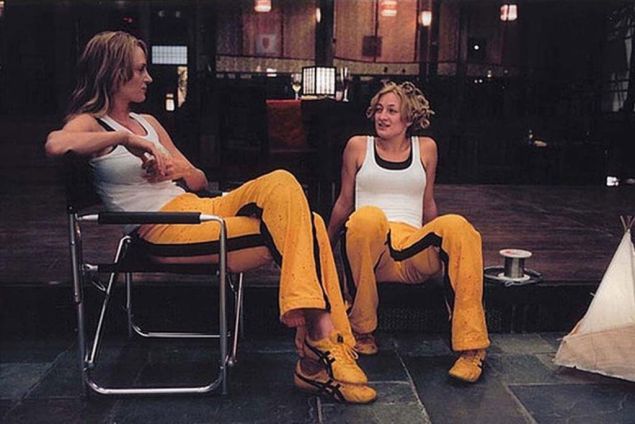

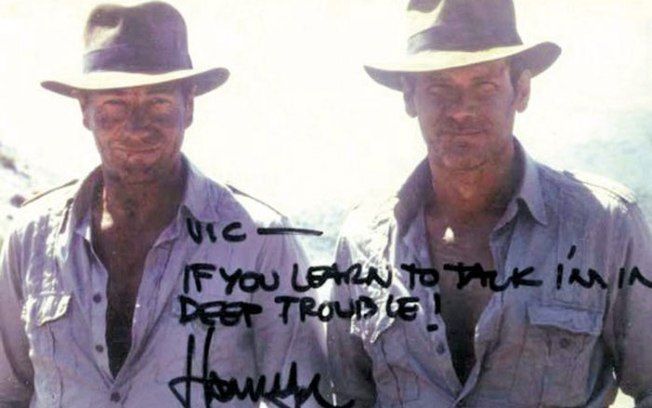

During the press junket for Mad Max: Fury Road, Tom Hardy had no qualms about this arrangement. For many of his interviews, he appears alongside his stunt double Jacob Tomuri (who is often not even credited by name in the video titles for these interviews, merely “stunt double”). Speaking to BlackTreeTV, Hardy says, “Jacob and I work cohesively together to create and bring you a character. So did Dayna [Grant] with Charlize [Theron] for Furiosa. This is like a hybrid of acting. So instead of not talking about it, we’re celebrating it.” In other appearances, he mentions the two or three other stunt performers playing the character of Max Rockatansky who all played varying roles, either as stunt drivers or motorcycle specialists. “My job, in a nutshell, was to say the words and to blend between the more visceral and dangerous stunts which then Jacob took over… At times, you couldn’t really tell the difference between the two of us.” This kind of out-and-out visibility for a stunt crew is rare.

In F for Fake, Orson Welles says that everything eventually fades away. “‘Be of good heart,’ cry the dead artists out of the living past. ‘Our songs will all be silenced, but what of it? Go on singing.’ Maybe a man’s name doesn’t matter all that much.” Things fade, yes. They are also deliberately scraped away.