Contending Forces

March 29th, 2022

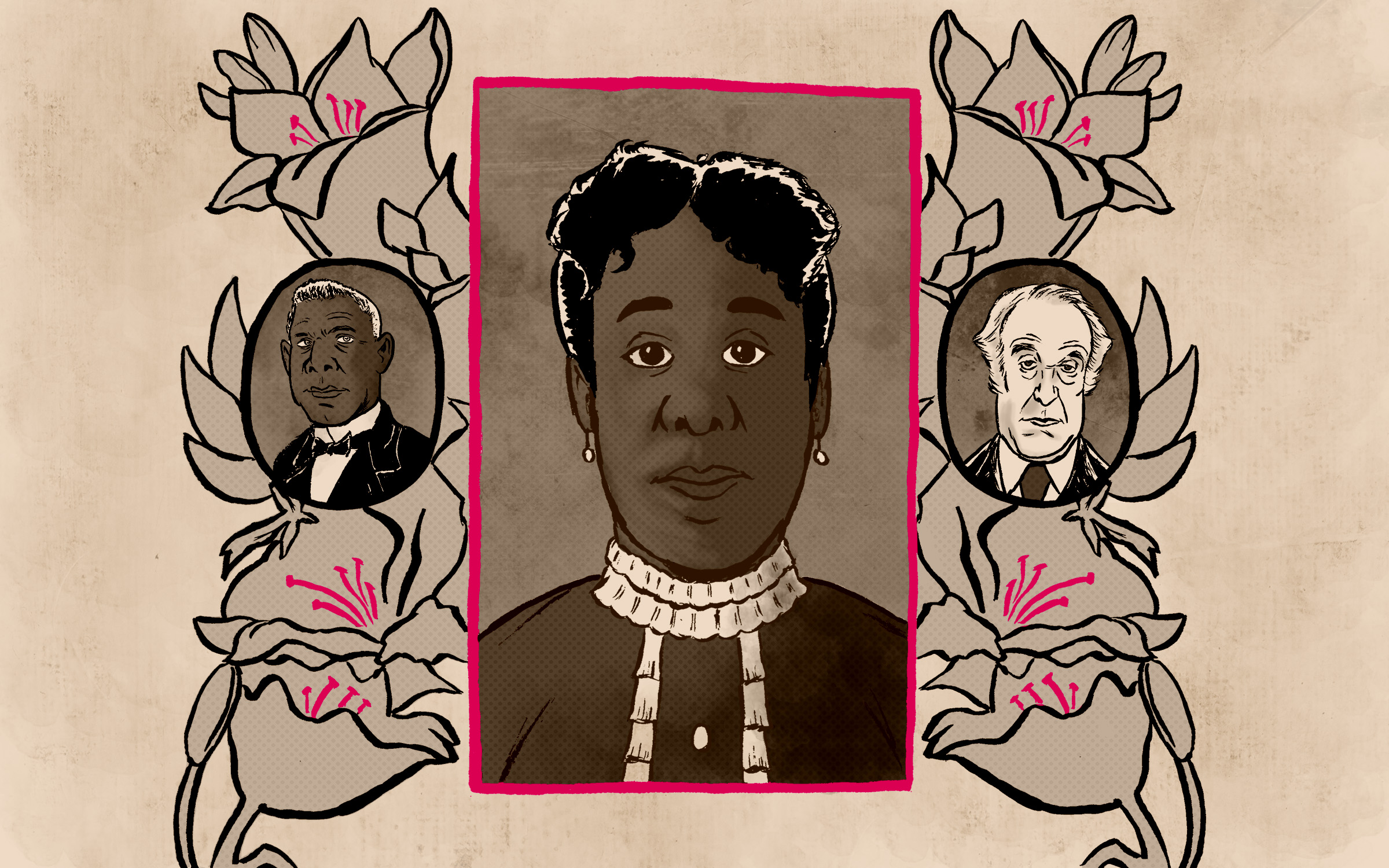

Pauline Hopkins, Booker T. Washington, and the Fight for The Colored American Magazine

1.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

More Reads

Uncategorized

Close Read: Thiago Rodrigues-Oliveira, et al.

Veronique Greenwood

Take the W: Entry Points

Katie Heindl

Credit: Creative Commons, johnmac612, CC BY-SA 2.0. When I started writing “seriously” about basketball eight years ago (before that, I wrote NBA fan fiction for David ...

Uncategorized