“I think you go after the TV stations if you are trying to mount an insurrection these days, or if you’re a totalitarian clinging to power—literary writers are nowhere on the radar.”

Things Nelson Algren and the Panero family have in common:

Being shaped by politics

Faith in literature

Loss of faith

Taking pleasure in pissing people off

On a Sunday afternoon in April, the Believer’s Hayden Bennett sat down with Aaron Shulman and Colin Asher to discuss their new books, both of which began as Believer essays. They met at a bar called Mission Dolores in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and drank and talked while trucks coughed past on 4th Avenue and the bar filled and became cacophonous. Shulman’s book, The Age of Disenchantments, tells the story of the Paneros, a family of Spanish poets whose lives and work map neatly onto the story of twentieth century Spain. Asher’s book, Never a Lovely so Real, is a biography of Nelson Algren, a once-renowned American author who began writing during the Great Depression and became famous after World War II, when he wrote The Man with the Golden Arm.

The Paneros and Algren share little in terms of biography, but both were affected by and influenced the politics of the eras they worked in, and so, the conversation at the bar soon focused on that commonality—teasing apart whether, and how, each subject believed writers should involve themselves with politics and what lessons their examples might hold for writers today.

THE BELIEVER: You both found a pretty obscure topic and brought it to the culture’s attention. How did you two, respectively, seize onto the Paneros and Algren?

AARON SHULMAN: In 2012, when I first saw El Desencanto, the 1976 cult documentary about the Panero family directed by Jaime Chávarri, I felt I had discovered something singularly strange and fascinating. I had so many questions, which, I think, as a writer is when you know you’ve found a subject you should spend some real time with.

I wanted to know about these people’s lives, their work, their politics, and what had happened to them before and after the film, never mind the story behind the film itself. And as it turned out, the whole 20th century of Spain culturally and politically was tied up in their lives. The deeper I got into the Paneros when I started interviewing people who knew them, reading their work, and tracking down archival documents, the more the family became a really expansive story that kept me engaged and challenged.

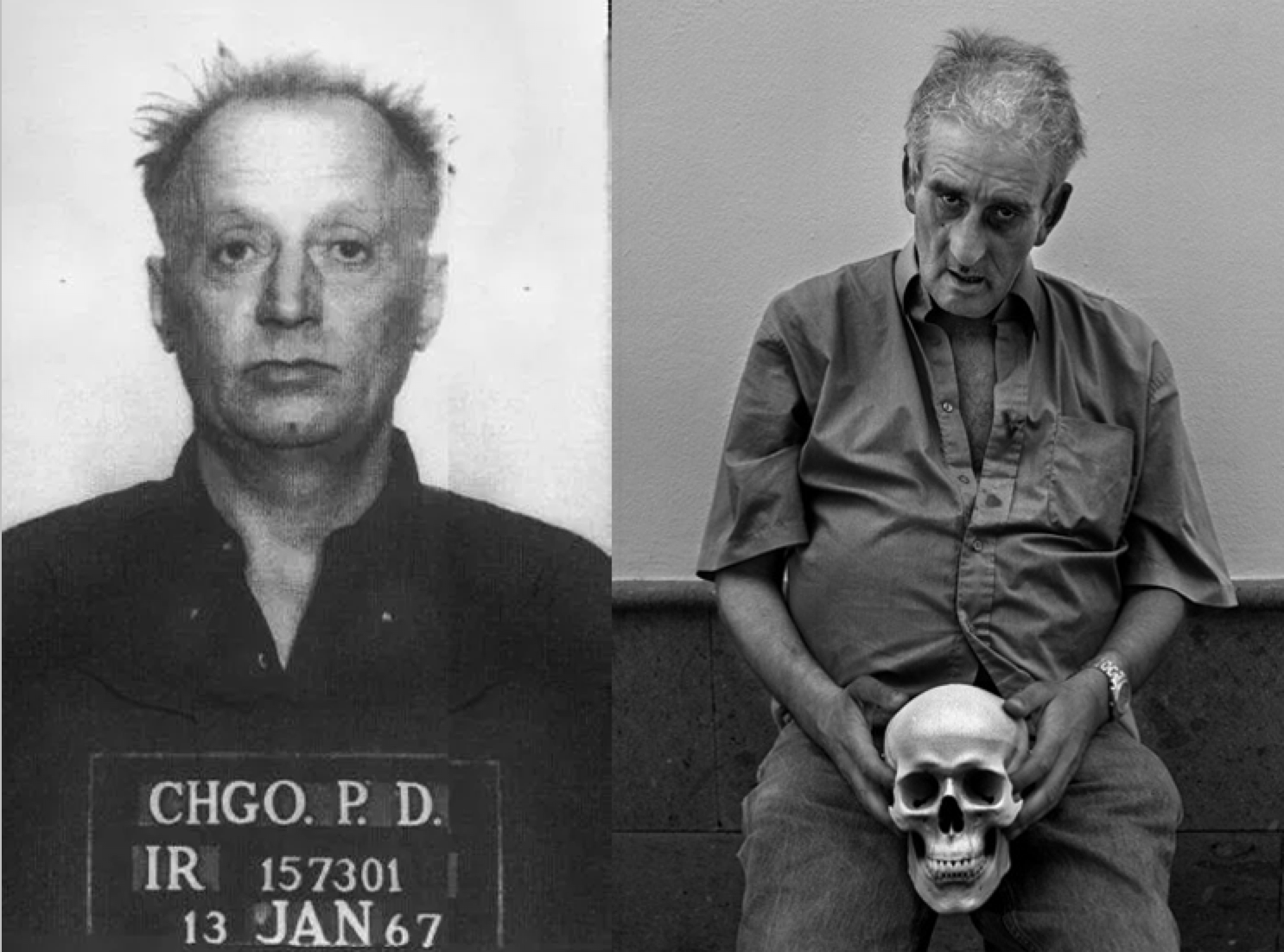

It was a story of complicated people in a complicated country: Leopoldo Panero, the patriarch, a communist poet before the Spanish Civil War and a fascist one afterwards; Felicidad Blanc, his muse and the matriarch of the family, who had had her own aspirations as a writer crushed under Franco and her husband’s career and personality; and their three sons, Juan Luis, perhaps the most like his father though also drawn to communism in his youth, Leopoldo María, a self-destructive poetic genius and political agitator, and Michi, a legendary womanizer and tabloid personality. I’ll be lucky if I ever find another story remotely as good as the Paneros’.

COLIN ASHER: I first read Algren’s work in 2009, the depths of the Great Recession. At the time, I was upset about the state of American literature. It seemed to me that no one in the literary scene was trying to reckon with the fact that the economy was a shambles, that people who had been striving and saving for their entire lives had lost everything, that people were, for the first time in decades, wondering about the stability of our economic system. I kept noticing a divide in the magazines I read most often—their reporting was routinely excellent and insightful, well-written longform that covered both the economic end of the crisis and the human cost. But when I turned to the fiction section, I would find stories that could have been published in any month of any year—vignettes of middle class ennui.

Complaining about that divide became a regular, and tiresome, part of my conversation that year until someone suggested I seek out Algren’s work, said he was a writer who focused on his moment. So I did. I bought a collection of his short fiction, poetry, and nonfiction called Entrapment and other Writings, and when I began reading it, his work struck me. It felt prophetic.

The first pieces in that book were written during the Great Depression, but they contain such insight into the emotional toll of that crisis that they seemed to be speaking to the moment I was living through. Deeper into the book, I discovered Algren trying to parse the causes of the opioid epidemic that followed World War II. There were also pieces anticipating mass incarceration, and nonfiction writing bemoaning the fact that the country’s post-war wealth had arrived without any accompanying emotional satisfaction.

Importantly, I also discovered that Algren often wrote about the purpose of literature. This struck me as well. These days, I rarely hear people discussing literature in those terms. Now, we focus on craft, on How Fiction Works or how to refine Draft No. 4, on shimmering sentences and beautiful similes—not on the role literature plays, or should play, in society.

AS: Often, in how we talk about writing nowadays, the craft part is inseparable from the crafting-a-career part. How can you become a published writer so you can get a job at an MFA program? That’s one example. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with that, we’re all just trying to make a stable living with health insurance and there’s no other way things could be. But sometimes we forget what literature should be really and always about: challenging power structures and received language, not just fashioning beautiful sentences and compelling plots, and the last concern should be about career prospects growing out of our writing, since pursuing those prospects in savagely capitalist America might influence what and how we write in negative ways.

I often think about something Leopoldo María, the middle Panero son and a famously transgressive poet and lifetime mental asylum patient, said, something along the lines of his literature being a revolutionary weapon. I think that’s important, so I try to ask myself if what I’m working on is weaponized or dangerous in any way. Not like anything I write is going to change anything in the world and I’m constitutionally not a combative person, but I hope that on some level I’m always probing taboos, uncomfortable truths, received notions, telling unheard stories, or making meaningful connections that have otherwise been hidden or ignored.

CA: Absolutely. That was Algren’s position as well. He believed that literature should be used to challenge authority, to assert the humanity of anyone whose humanity was being denied. For him, writing was generative—it is one way that we define ourselves as a people and as a society, and he saw it as his role, and the role of every other responsible author, to ensure that society acknowledge the existence of people many readers would rather ignore.

Later in his life, Algren became depressed about the state of his career and the publishing industry and lost faith in literature. At that point, in the late 1950s, he wrote heart-wrenching letters telling his friends that he felt lost. He said, in essence, When I was coming up in the 1930s and 40s writers were fighting to have a say in the future of humankind. They were asking big questions and making bold proposals. Twenty years later, he felt, no one was interested in taking risks like that—people wanted to write books that had a chance of selling, not books that had a chance of altering the course of history. Fairly or unfairly, he continued to believe that until he died in ‘81.

It took me a long time to realize how crushing that loss was for Algren because the ideas that guided his work early in his career are so alien to the way we discuss literature these days. He thought, in the 1930s, that his books, and his friends’ books, had a role to play in that era’s political and economic conflicts. He liked to say that his friend Richard Wright’s first novel, Native Son, left a mark on the “conscience of humanity.” No one, in my experience, discusses literature in those terms today.

But I think Algren’s early faith in literature would have made perfect sense to the Paneros. I dogeared a number of pages in your book, Aaron, and I think the first was at the beginning of the chapter where you talk about how both sides of the Spanish Civil War relied on poets to boost morale and recruitment. If someone said the same today, they’d have to be joking.

AS: The period before and during the Spanish Civil War was very unique. What I really loved about the pre-war era in the 1930s, is that you have all these poets—Pablo Neruda, García Lorca, Miguel Hernández, and many others—living in Madrid and they were important public figures. They were influencing the culture with their work, and writing in newspapers in ways that were very relevant to what was going on. Then, you had the Spanish Civil War and, like you were saying, there was a war of poetry parallel to actual warfare taking place both inside Spain, between the Spanish writers who were in Franco’s camp and then those of the Republic, and then outside Spain too, between people like Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound.

The Republic definitely had the better writers. There’s a great Spanish author, Andres Trapiello, who has this famous quote that the writers in Franco’s army won the war but lost the instruction manual for literature. Meanwhile, in the Republic, they lost the Civil War but they wrote indelible verses. A lot of it was propagandistic, yes, but much of it transcended its political use and was true literature. Franco could only silence these voices by killing the poets, as in the case of García Lorca, or imprisoning them, as in the case of Miguel Hernández (who died in prison), and with the other writers in exile he could try to keep their works from entering Spain through censorship.

The Republic definitely had the better writers. There’s a great Spanish author, Andres Trapiello, who has this famous quote that the writers in Franco’s army won the war but lost the instruction manual for literature. Meanwhile, in the Republic, they lost the Civil War but they wrote indelible verses. A lot of it was propagandistic, yes, but much of it transcended its political use and was true literature. Franco could only silence these voices by killing the poets, as in the case of García Lorca, or imprisoning them, as in the case of Miguel Hernández (who died in prison), and with the other writers in exile he could try to keep their works from entering Spain through censorship.

This would feel so strange today, the idea, firstly, of making it a priority in a military conflict to publish and circulate poetry to aid your cause, and secondly and conversely, to make it a priority to imprison and kill poets on your opponent’s side. It’s such a diminished role of literature in society now. Today it’s that we need to kill the YouTube influencers, the people with the most followers on Twitter.

BLVR: I mean, totalitarian states will go after Twitter accounts, right?

AS: Yep.

CA: I think you go after the TV stations if you are trying to mount an insurrection these days, or if you’re a totalitarian clinging to power—literary writers are nowhere on the radar. In Algren’s time, however, the FBI placed writers on lists of people who should be detained in the event of a national emergency, to prevent them from sowing chaos or taking part in an uprising. Algren was on it for years. I believe James Baldwin was as well. This, too, is a notion that feels very alien. I mean, choose your favorite writer, the one with the deepest insights and most incisive social critique… can you imagine that person being detained to prevent them from spreading their ideas during a national crisis?

AS: It’s funny, because here I was a minute ago saying we need to be dangerous and weaponized and transgressive in what we write, but did I really do that in writing about the Paneros and how their story relates to the present? I’m not sure. I can criticize the culture or other writers but instead of me as a writer figuring out how to be dangerous in engaging directly with the present, I turned to the past. I fall prey to this nostalgic looking back.

CA: I don’t think we’re closing our books off from the present. What we’re each trying to say is that the past, the example set by earlier, more socially engaged generations of authors, should be part of the conversation today.

AS: And I suppose the way you look at the past and interpret it can be dangerous, in both good and bad senses. But then there is a part of me where I’m just daydreaming about “Remember when writers were important,” and that feels kind of pathetic.

CA: I hear you, but there’s another way to interpret that. Instead of thinking of it as daydreaming, you could say that we both hope to influence the present by searching for precedent for our ideas in the past. I mean, nostalgia is important. Every successful political movement knows that, and I don’t feel embarrassed to say that I openly long to live in the sort of cultural moment when a debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley was considered a major social event. We’re just trying to draw attention to people who had priorities we share. I think there’s value in that. We’re saying, simply, this—radicalism, social engagement, politics, literature that responds to and struggles to make sense of the political moment of its creation—is part of the literary culture as well. Literary history doesn’t begin in the 1960s with the explosion of MFA programs. There was a time before that, generations and generations of writers we can name as our forebears.

AS: I think that’s what we’re really talking about. This idea that poets are important and writers are important.

BLVR: To go back to earlier, what was the first Algren book you read when you thought, “Oh, I should write about this stuff,”? When did the engagement level change?

CA: The first Algren book I read was the collection I mentioned earlier, Entrapment and Other Writings. I chose it because it was the only Algren book on the shelf in the store I visited, but it was the perfect text because it introduced me to Algren’s prose as well as his ideas about literature. The book grabbed me in a way that Algren’s novels may not have, but after I read it, I committed myself to reading all of Algren’s major works.

I can’t remember precisely, but I think I read Algren’s second novel, Never Come Morning, next—then, Chicago: City on the Make, The Man with the Golden Arm, The Devil’s Stocking, and A Walk on the Wild Side. I think that was the order. By the time I finished that run, I knew I was going to write something about Algren. I started sketching out some thoughts soon afterward, and then pitched the Believer on the idea of an essay. Writing a book didn’t even occur to me until after the essay had been published.

BLVR: What about you, Aaron?

AS: After I was sent the PDF proofs of my Believer piece about El Desencanto in early 2015, something clicked, and I started imagining it as a book. I think that at that time I thought I had found my identity as a writer (I was revising a novel I’d never publish, whose failure would be a huge emotional blow), but I hadn’t really, and the Panero sons somehow helped me with this, maybe because all three were so different, and so each helped me explore different parts of my identity. Apart from Juan Luis in some of his posturing, none of them came from a hyper-manly literary tradition, which in the US Hemingway I think managed to institutionalize for nearly a century, and which I didn’t relate to.

With the Panero brothers, their father was a product of the wildly patriarchal Franco era (legally speaking, women were more or less on the same footing as children), which means, like, you drank all the time, yelled at your wife and kids, and you cheated, and none of this was a big deal. But then there was the son Leopoldo María, who was a bisexual and sadomasochist, who created this whole transgressive, rebellious persona in a way that was a very taboo-smashing political act. He was really trying to rebel against Franco and all that he represented, and part of that was through the rejection of traditional masculinity. And then his younger brother, Michi Panero, rebelled with a sort of dropout cynicism as a flaneur and slacker and self-proclaimed loser. His playboy side, on the one hand, was very laden with machismo, but on the other hand, being so promiscuous also went against Catholic mores, which was the foundation of Spain.

BLVR: The Paneros were very different people, but also very different writers, yeah?

AS: Definitely. Looking at the literature of all five members of the Panero family made me wonder if all writers are oriented either inward or outward, if their writing is an excavation of what’s inside or a reporting on what’s around them. Of course, it’s usually a blending of the two, but I think most writers lean one way or another.

Algren, though he was mainly a novelist, almost seems to me in Colin’s book like a reporter more than anything else. His MO was like a journalist in how he did research, and then he would fictionalize his reporting. With the Panero family sometimes it seemed like all they had was their navel. A fascinating navel, for sure, and one that was affected by their society and their family history and said something about Spain as a whole (the personal is political, as the saying goes), but nevertheless navel-gazing. It was very much looking at who we are, our lineage, and we’re going to build that into a monument of literature, whereas Algren was a novelist out in the world, reading reality. He was really bringing the news.

CA: Yes, he was very open about that. He said that people who wanted to write needed to be in touch with the world, and he told anyone who would listen that writers should avoid other writers and the formal study of literature. He made this argument early in his career and continued making it until his death. In the first essay he wrote about writing, he said: “All the manuals by frustrated fictioneers on how to write can’t give you the first syllable of reality, at any cost, that any common conversation can. All the classics, read and re-read, can’t help you catch the ring of truth as does the word heard first-hand.”

Algren liked to say that he wrote his own books by finding spaces where human beings were in conflict—courtrooms, police lineups, street corners, SROs, bars. Then, he sat down and watched, listened, and felt what was going on around him. He worked, in some respects, in the way creative nonfiction writers work today, which I often reflect on. I wonder whether he would have been a novelist at all if he had been born sixty years later. All the energy and enthusiasm for writing about the portion of society he was interested in has gravitated to creative nonfiction now, which wasn’t an established part of the literary canon yet in the 30s and 40s when he was getting his start.

BLVR: If he were writing after Tom Wolfe, he might have seen that differently.

CA: Yes, if he were born deeper into the twentieth century, I think he would have written something like Random Family, There are no Children Here, or Life on the Outside.

AS: On the one hand it’s because genre-wise there’s been more and more permission given to really write non-fiction as if it were a novel, thanks to the New Journalists, but that happened after Algren’s heyday. Then I do think writers are pushing themselves to a depth of reporting which maybe people didn’t go that deep before. But of course, there are still those novels which have a nonfiction-ish tapping into reality. Rachel Kushner’s recent book, The Mars Room, for example. She is weaponizing her work, making it dangerous, and I do think lots of others are too. I think right now this is happening most with the work of writers from groups that have historically been marginalized, and in a lot of cases the mere fact of their voices being heard louder and with a bigger platform is a revolutionary weapon of sorts. In this sense, editors can be “dangerous” in constructive ways more than ever before, maybe putting their careers on the line to put out work they believe in.

CA: Of course, of course—you’re right to point this out. The politically and socially engaged strain of literary fiction we’re talking about isn’t dead. Kushner’s Mars Room is evidence of that, and so are Sergio De La Pava’s books, Jesmyn Ward’s novels, and others. Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen comes to mind—the book’s title character has been warped by both her environment and her own weaknesses in a way that I think Algren would appreciate.

And I should be careful, too, that I am not conflating naturalism and social engagement. Other styles lend themselves to social engagement as well, and produce books that challenge with their ideas. Here, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale come to mind—both incredibly impactful works of imagination.

I suppose it’s more a question of degree and emphasis. I think that if you are getting your start as a writer now, and you’re interested in being a part of both the cultural and political discourse, you get the sense that you should be writing creative nonfiction.

On one level, I have no problem with this. That’s my form, after all. But I think there is something lost when fiction writers abandon social engagement. The creative nonfiction writer can speak to their subject, and will be asked to, but a great novelist has the right to speak about humanity, the human condition, the soul.

I was reflecting on this recently, while watching I Am Not Your Negro, the James Baldwin documentary. Baldwin has been having a moment lately, obviously and deservedly. I think most of his resurgence has to do with his writing, but some of it has to do with the way he contextualized his ideas when he spoke publicly. When he addressed an audience, you see this in the documentary, he spoke with an incredible amount of presumption—and that’s not a knock. He had a way of speaking that reflected the level of respect literary writers used to be afforded. He used capacious language like, “we.” He spoke about humanity as an extension of himself, and of himself as an extension of humanity, and when I heard him doing so, I realized I had been longing for that. Writers, these days, it seems, always speak in the first person, speak humbly, or, if not humbly, then in language so specific and precise that there’s little risk involved.

But in Algren’s day, in Baldwin’s day, that wasn’t the case—there was a presumption then that a novelist had a right to speak their piece about the state of humanity if they had been writing long enough, well enough.

AS: I think in a way you would get attacked for presuming that, especially if you’re a man. I’m not saying that is a bad thing. Or maybe now, as a man, especially as a white man (as we both are), you have to earn that right to speak more than ever before, which is a good thing. It’s about trust more than anything else, maybe. And it seems what we’re finding today is people still trust Baldwin, and since I love your book I’m hoping people rediscover Algren and trust him too, because he had tremendous intelligence combined with a huge heart. In contrast, with the Paneros, I think the whole point is that you can’t trust them. Not only are they unreliable narrators, but they love offending and provoking. That’s their form of literary political activism, but they are most valuable in the conversations their work and behavior incite, rather than the time-tested wisdom of their words—though they do have some really moving and important gems, like Leopoldo María’s about literature needing to be dangerous.

CA: Well, like anyone, Algren wasn’t reliable in all ways at all times. He had his blind spots and his biases. I wouldn’t want people to place faith in his views uncritically, but he was a person of conviction, a true believer in the power of literature, and I would love for his ideas about the institution to gain adherents. As I said earlier, he spelled those ideas out in a number of essays, but lately I’ve been feeling that the truest expression of his literary vision appears in one of his novels.

In The Man with the Golden Arm, a defrocked priest claims that he was forced out of the church because he believed that, “We are all members of one another.” His words trouble a police captain, a man who has spent his career judging and condemning people, and result in the captain experiencing a crisis of conscience. In time, the captain begins to understand that he is no better than the men he judges each night, that he is capable of committing every sin that has ever been confessed to him. This realization provides him with a chance at redemption, which he rejects, finally deciding that it is safer to reject the common bond of humanity he shares with the arrested men who parade before him each evening.

When I first read the passages about the captain, I read them as a critique of the police. But over the years since, I’ve realized that the officer’s crisis of conscience is less important than the defrocked priest’s declaration of values because his values are Algren’s as well, and the idea that humanity is a single organism composed of many individuals bound but an immutable bond is the idea responsible for the creation of Algren’s best work. He, to strain the metaphor a bit, is the defrocked priest, a man abandoned by his religious order but intent on doing good works despite that fact.

If he ever truly had the right to speak in grand terms about humanity using “we,” it was because of that conviction. And if his work has any lasting relevance, which I believe it does, it’s for the same reason. Understanding that “we are all members of one another” led Algren to recognize that any attempt to dehumanize a portion of society thought to be unworthy of respect, any punishment or diminishment, would be visited on the remainder of society in due time.

AS: In other words, Algren is still really relevant, which makes me wonder how my book is or isn’t relevant to the present. I was writing it both before and after Trump’s election win, and the subsequent emboldening of white-supremacist and ethno-nationalists, so I’ve thought a lot about the resurgence of fascism, and the connective tissue between Spain in the past and the US today. And there are lots of connections: young men believing they are “saving” their civilization from decay and contamination, ethnic and regional hatred and anti-semitism, aesthetic stylization (haircuts and clothing), and so on. The history of the Spain that the story of the Paneros traces has been been helpful for me in understanding that this thing hasn’t come out of nowhere, that there is a long tradition of fascism, and that this ritualistic mystique and selling of an idea to young men that they’re saving civilization has been around for a long time. And writers will emerge at some point to tell the stories of our current time in timeless terms. They’re emerging already.