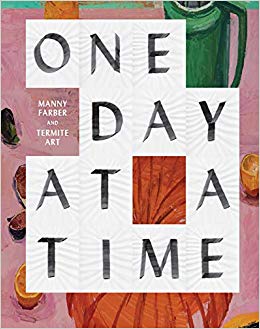

One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art

Museum of Contemporary Art, Companion Book by Helen Molesworth

Walking into “One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art”—the final show at Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art with former chief curator Helen Molesworth at the helm, unfortunately, but what a way to go out—I found that my first task was to get my bearings. Painter Manny Farber’s canvasses are crowded with stuff: notes with obscure directives that take the character of mantras (“Order everything in place,” reads one), suggestively placed eggplants, broken chocolate bars scattered across a desk, staplers perched next to asparagus stalks, miniature women shimmying out of or into bikinis, tiny cowboys strutting cutely, out of context. Standing before ones of these paintings, it can be difficult to figure out where your eye should land, where Farber’s compositions want you to enter.

Take a painting like “Rohmer’s Knee:” its circular canvas is populated by bikini-clad women wandering a landscape of watermelon slices, rulers precariously balanced upon cheese wedges, and magazines thrown wide open to the viewer. It is composed as a closed loop of incessant action; there’s no obvious resting point, no static moment. A model railroad track—circular, of course— sits like a halo at its center; picking up on its cue, my eye wanders in circles around the canvas.

Before he traded his New York apartment for a position teaching art at UC San Diego in 1977, Manny Farber worked as a film critic, and there is indeed something filmic about his paintings. They’re imbued with a chaotic sense of movement that goads the viewer into unceasing motion. It’s the only way to enter these paintings, which free-associate Farber’s obsessions (included but not limited to Westerns, candy, the films of Fassbinder, and women) into miniature dramas. In his most famous essay, “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” (which Molesworth includes in the exhibit’s companion volume), Farber decried the lethargy of “masterpiece art” that subdued an artist’s personal interests to the requirements of monumental compositions obsessed with grand statements. Such art found an artist’s vision “squandered in pursuit of the continuity, harmony, involved in constructing a masterpiece.” In the masterpiece’s place he lionized “termite art,” which was concerned only with giving voice to quotidian “in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn’t anywhere or for anything.”

Farber’s paintings feel like a visual companion to his critical notions. Every corner of a canvass has the potential to house a minor drama: the interplay between black and yellow that animates “Patricia’s a Legend,” for instance, or the tension springing from the way a ruler balances upon the model train set in “Rohmer’s Knee.” You’ve got to let...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in