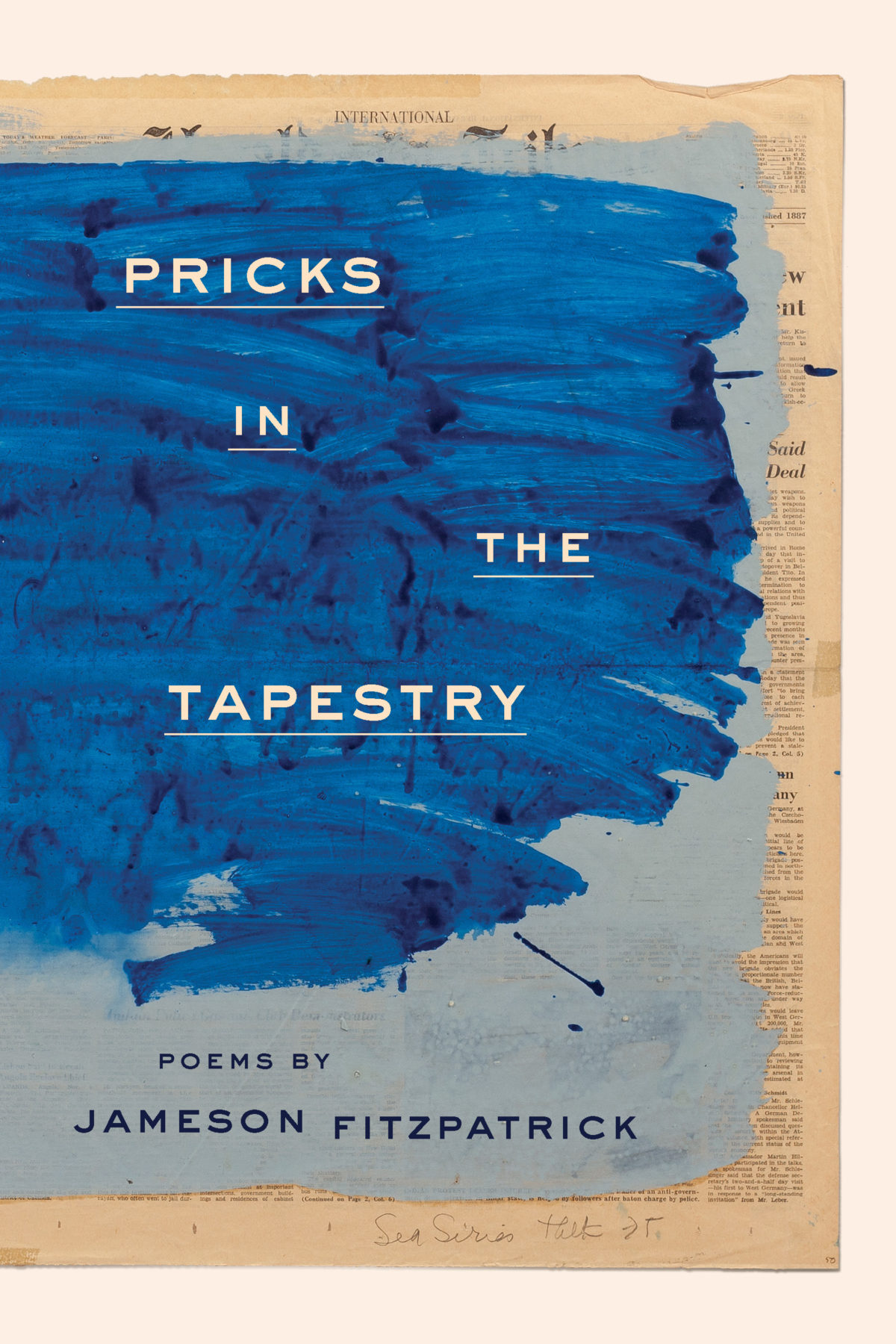

Format: 87 pp., paperback; Size: 6×9″; Price: $18; Jacket Art: Paul Thek / designed by Zoe Norvell Publisher: Birds, LLC Number of boys mentioned in the poem “Selected Boys: 2003-2008”: 17 Number of base pair deletions homozygous carriers need in the CCR5 gene in order to have resistance to HIV: 32; Another book by the author: Mr. &; Representative Passage: But isn’t the mind the body. / Isn’t mine. And what has / been done to it, and how: / plucked like a flower / versus / plucked like a string.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in