In 1875, the photographer Eadweard James Muybridge stood in a field of dead cornstalks and photographed a large stone with a hole in the center and a man’s face visible through the hole. He published the photograph in his Central America Illustrated by Muybridge series, naming it “Ancient Sacrificial Stone, Guatemala”—leaving out the fact that the stone was an astronomical observation device that had nothing to do with sacrifice. But illusion in documentation was familiar to Muybridge: in earlier photographs he had added clouds to blue skies, and, as with the stone, changed titles to alter content and context. When the U.S. government paid Muybridge to document the Modoc War in southern Oregon and northern California, he took a photograph of a soldier sticking a rifle through a pile of stones and named it “Modoc Brave on the Warpath,” even though it was actually an Apache scout working for the U.S. Army, posing on a warpath calm enough to allow for a minute-long exposure.

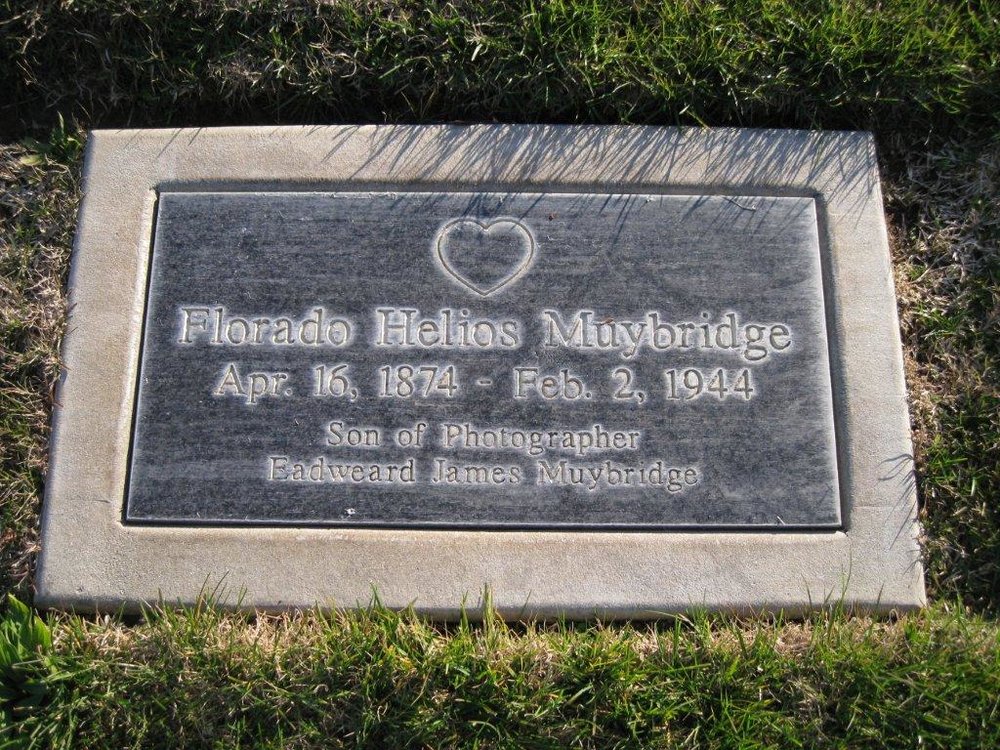

In 1874, while Muybridge was away to photograph that war, his wife, Flora—twenty-three years old to his forty—had a child. They named him Florado, a composite of their own names, and gave him the middle name Helios, from the Greek god of the sun; it was also the name Eadweard had given his studio and even used to sign and display some of his earlier photographs. When Florado was seven months old, Eadweard found a photograph of him with the inscription “Little Harry” on the back. After speaking to his wife’s nurse, he learned that Flora had been having an affair with a Major Harry Larkyns. That same day Muybridge got on a boat and then a train, convinced a liveryman to give him a nighttime carriage ride to Calistoga, found Larkyns playing cribbage in a parlor, told him “My name is Muybridge and I have a message for you from my wife,” and killed him with a shot to the chest.

Photographer and filmmaker Hollis Frampton posits that the firing of the pistol marked the precise moment that fueled Muybridge’s subsequent obsession with time and with the act of picking it apart, which is most evident in his photographic sequences of hundreds of different people and animals consumed in hundreds of different acts. To take a photograph, to conceive a child, to shoot a man: all rely on a single instant to create an image, a human being, a corpse.

After Muybridge killed Larkyns, he contested the parentage of “Little Harry,” and after Flora died he returned from Central America and consigned the boy to San Francisco’s Protestant Orphan Asylum. According to Rebecca Solnit, Eadweard came to visit a few times, but after Florado left...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in