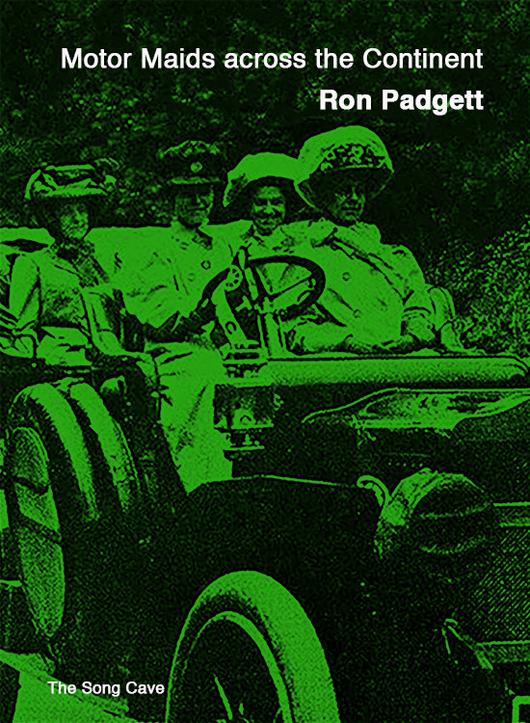

I met with poet Ron Padgett at his East Village apartment, where he and his wife have lived since 1967. He and I sat surrounded by books, archive boxes, and artwork. I asked about the oil painting just above my head, a navy blue background with thirty-odd cigarette butts falling every which way. Padgett told me it is by Joe Brainard, the late writer and artist, and Padgett’s close friend since their childhood in Oklahoma. Padgett wrote about him in Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard (2004). His most recent book, Motor Maids across the Continent, came out in the spring of 2017. Fifty years earlier he had found an old adventure novel intended for teen girls, The Motor Maids across the Continent (1911), in a used book shop. Later that day his teacher at Columbia, Kenneth Koch, took the book out of his hands, crossed out a few passages, and on page 3 wrote “The End,” kicking off Padgett’s own exploration and transformation of the found material.

Padgett is known not only for his poetry but also for his translations of Blaise Cendrars and Guillaume Apollinaire. Since 1960 he has been part of an extended circle of writers, artists, filmmakers, and modern dancers, mainly in New York, such as Koch, Brainard, Ted Berrigan, Rudy Burckhardt, George Schneeman, Bill Berkson, Kenward Elmslie, Alex Katz, Anne Waldman, Douglas Dunn, Trevor Winkfield, Frank O’Hara, Paul Auster, Bill Corbett, Glen Baxter, Alice Notley, Charles North, Clark Coolidge, Tom Clark, David Shapiro, Bill Zavatsky, Peter Schjeldahl, James Schuyler, and Jim Dine. Richard Hell has cited him as a great inspiration. Most of the poems in Jim Jarmusch’s film Paterson (2016) are by Padgett. Next year Coffee House Press will issue his collection of new poems, Big Cabin.

—Stephanie La Cava

I. Dada Heroes / Picabia / Duchamp

THE BELIEVER: What’s in the Picabia box high up on that bookshelf?

RON PADGETT: I really don’t know. I haven’t taken that box down in a long time.

I read about Picabia when I was in college in the early 60s and had seen a little of his work at MoMA. I got interested in Dada and then in 1965 I went to Paris for a year. That’s where I got really interested in him, because the resources there were so much greater. The books in that box, I bought most of them in 1965 or ’66.

BLVR: Were you interested in all phases of his work, or any particular moment?

RP: I was interested in the whole package. He was such an interesting and mysterious character, and I liked not only his writing and visual art, but his editing too—391—and the magazines that he contributed to. I think what appealed to me originally was how uncontainable and ornery he was, mercurial and self-contradictory—all those wonderful Dada-type things. I knew he was somewhat tormented as well, but he was also very talented.

Back in the 60s and 70s, people talked about mainly his mechanical drawings or the Dada work, not the later pieces—the so-called transparencies or the bizarre realistic painting he did, the portraits.

I didn’t particularly enjoy looking at many of those later works (some of which were brilliant), but I recognized that they were all part of the same adventure that made him the great Dadaist. He did things you weren’t supposed to do in art, a bit like Duchamp but without the quiet reserve.

BLVR: Were you friends with Duchamp?

RP: Not friends, no, but I did meet him a few times. And I translated a book of his, a book-length interview in French by an art critic, Pierre Cabanne. In English, it was published as Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. My translation was Conversations with Marcel Duchamp, but I didn’t have the control over the title.

BLVR: Did you ever talk to Duchamp about the translation afterward?

RP: Not afterward, but I talked to him about it before, because I had some questions for him. I remember there was one word I didn’t know, because my French wasn’t very contemporary. I asked him about the word and he gently explained what it meant.

BLVR: What was the word?

RP: It was the word store, meaning an awning or blind. It wasn’t in any of the dictionaries I had. There was no internet, either.

Several years before that I had run into him at an art gallery on Madison Avenue, maybe around ’63. It was a Kurt Seligmann show. I was the only visitor in the gallery, but I heard two voices in another room, and one of them sounded French. I was about to leave when I saw a gentleman walking out the door and I realized it was Duchamp. I had a big crush on his work—I was 21 or something like that. I followed him down Madison Avenue to the corner, where he stopped for the light, and I walked up next to him and said, “Excuse me, but you wouldn’t by any chance be Marcel Duchamp, would you?”

He turned his head and looked at me with a wry little smile and said, “I might be.”

I gushed out, “I just want to tell you that my poet friends and I really love your work.”

He nodded and said, in a very courtly way, “Thank you.”

The light turned green and I said, “Thank you. Goodbye.”

He said goodbye and that was that. When you’re young it’s thrilling to meet one of your gods.

The next time I met him was when I went to see him here in New York at his apartment to talk about the translation. His wife Teeny ushered me into the front room of their apartment. A beautiful sunlight was coming in through the windows that gave onto West 10th Street. He was sitting in a wicker chair that had a high back that flared out above his head, like a Chinese throne. He looked good in it, very much at ease with himself and with the world. I remember how avuncular he was, kind and accepting, which made it a lot easier for me to be in his presence. After talking with him for a while I forgot my fear of being there and I realized it was all going to be okay.

II. Translator / Novelist / Biographer / Poet

BLVR: You said you didn’t know French very well.

RP: I didn’t, not really well.

BLVR: So how did you become translator of poets like Guillaume Apollinaire, Pierre Reverdy, and Blaise Cendrars?

RP: Mostly out of sheer persistence. My spoken French was bad until I went to Paris to live and then things started to click a lot better. Over the years, I read a lot of books and I did a lot of looking up words in dictionaries and I had bilingual friends who helped me.

BLVR: When I read about you and about your contemporaries in the New York School, about Joe Brainard, for example, there’s always the use of words like “kind,” “generous,” “positive,” “happy.”

RP: Yes, there’s a certain amount of joy and happiness—even fun—among those writers, and Joe’s niceness was legendary. But take a poet like Frank O’Hara. There’s a lot of anxiety and anxiousness and even some depression in his work, along with all the energy and joy and pleasure. In John Ashbery too, where sometimes one finds a meditative melancholy. It comes out in Kenneth Koch’s later work, as well.

BLVR: Since you bring up Ashbery, I’d love to hear a little about him.

RP: One of the things that surprises me is how much I miss him, because I miss not only him, I miss knowing that he’s alive. He had a long, productive, successful life, so it’s wrong to think he got short-changed. He made out pretty well! But from my point of view, I just miss knowing he’s here. It’s comforting to think that someone you admire a lot is out there still being productive at an advanced age. I felt that way knowing that de Kooning was alive, as well.

BLVR: What was your relationship with de Kooning?

RP: I met him just once. He came to our house for lunch, with Joe LeSueur and Clarice Rivers. Joe Brainard was there too.

BLVR: How was that?

RP: It was wonderful.

BLVR: What about Jane Freilicher?

RP: Jane and I were always very friendly but never what I’d call close. I admired her a lot, not only her work but also her person. People say how witty she was—they’re bang-on. She was really sharp. Her wit and irony were so sparkling and dry and quick that I can’t remember any examples. It’s like asking someone to count the bubbles in a glass of champagne. You can’t: they’re rising and popping and disappearing. Another person like that was the poet Anne Porter, who was the wife of the painter Fairfield Porter. Anne looked like a little old lady in a children’s book who bakes gingerbread and quietly shuffles around in the background of the kitchen. But talk about smart and witty! And a wonderful poet.

BLVR: I was looking at some of the pictures that Joe Brainard did for Jane’s baby shower.

RP: Yes, Kenward Elmslie and Joe Brainard also did a whole book called The Baby Book, inspired by the birth of Jane’s daughter.

BLVR: It was super charming to see those sweet drawings. She was the girl amongst a bunch of guys. And they all loved her. But that makes sense that it was based on the wit, and also this idea of the painter among poets, and the sort of landscape between the visual and the literary arts.

RP: Those landscapes tended to get blended. In high school, I myself was making visual art and writing poetry.

BLVR: And this was in Oklahoma?

RP: Tulsa. In high school Joe Brainard and I became good friends quickly. He was the school artist, clearly super-talented. After we got to know each other I showed him some of my artworks and [Laughter] there was a strange silence, followed by “Hmm-hmm, interesting.” [Laughter] I suddenly saw them through his eyes and realized there wasn’t anything special about them. Joe’s gentleness made him not want to say anything bad, you know. All I had to do was look at his work and I could see where the real talent was. So at that point I tapered off in my art production, fortunately! Later Joe became a writer, mainly through the personal influence of Ted Berrigan and me.

BLVR: Tell me about how he stopped making art.

RP: That’s been overstated. He stopped showing, for sure. He had grown tired of the art world, which had become very commercialized, with a lot of pressure to have a new show every two years and to succeed and schmooze and to be “cutting edge.” The “hot” work was more and more aggressive and in-your-face and loud and big.

BLVR: He liked small, right?

RP: He liked intimate, he liked personal. And he shied away from the trend toward impersonal art made for collectors, banks, and corporate offices. At the same time, he also grew disappointed in his own production. He set extremely high standards for himself, standards he couldn’t meet. So I think he finally told himself that there’s nothing in the world that says he must keep working like a maniac, because he worked very, very hard for a period of about 17 or 18 years.

BLVR: I read the thing about the amphetamines, that was true? He’d just keep going all the time?

RP: No. He wasn’t always on speed, but he did go on jags with it and work for 24 straight hours. Then he would come down and cool it for a while. But he really loved to work. In fact, he usually worked every day, with or without speed. He was enormously productive, more than most people are in their lifetimes. My guess is that he got to the point where he asked himself,“Do I really have to base my life on being an artist? Isn’t there something else I might do or be? Is that where my self-esteem comes from, because people praise me for what I produce?” So he decided to give it a rest.

In 1992 he came back and did a suite of ink drawings for a book by Kenward Elmslie, Sung Sex. He did some other works a little later too, but to my knowledge he never showed them to anybody. He even went back to art school, a place called something like the New York Academy of Art, which offered old-fashioned classical beaux arts training —still lifes, landscapes, nudes. And for a while he was part of a private drawing group of artist friends, including Elizabeth Murray. From all this he left behind maybe 20 or 30 large nude figure studies in pencil and Conte crayon, unsigned and undated. I think he might have even forgotten he had them. After he died we found them in the back of a closet in his loft. By that time he’d gotten rid of most of his possessions. He wanted to be like Ghandi, who had died with fewer than ten possessions—a pair of glasses, some shoes, a notebook… Anyway, these 20 or 30 nude drawings were beautifully done, all well after he “stopped making art.” So really he kind of tapered off.

BLVR: Is there anything of his in this apartment?

RP: Above my head. [Pointing.]

BLVR: Ahh. Pansies.

RP: That’s a still life from 1968.

BLVR: What about Anne Waldman?

RP: She and I are old pals. We met in 1967, here in New York. She’s good-hearted and generous, full of energy. When I first met her, she and the poet Lewis Warsh lived in an apartment on St. Mark’s Place. Fresh out of college, they were footloose and fancy-free. The rent was cheap—you could live on almost nothing in those days. They had an all-night salon every night. Quite a few poets and artists hung out there.

BLVR: Who, for example?

RP: Ted Berrigan, Dick Gallup, Jim Brodey, Bernadette Mayer, Donna Dennis, Martha Diamond, Larry Fagin, Michael Brownstein, Jim Carroll, to name a few. And there were a couple of friends from Anne’s childhood, one of whom became an Olympic skier. People would actually write poems together there and listen to music and gossip and carry on. It was all quite convivial. Anne was already an extraordinary person, especially given the male-dominated environment. She didn’t let the guys push her around. She was good-humored and she had a radiance.

BLVR: Was there any place where everyone went?

RP: Well, the St. Mark’s Poetry Project was the major focal point. There was also a pool hall on 14th Street called Julian’s Billiard Academy. It was an old-time pool hall, with tobacco smoke and chalk dust hanging in the dim light, just like in film noir, and for a couple of years some of us liked to shoot pool there late at night. George Schneeman and I did it a lot, Ted Berrigan sometimes. Jim Carroll dropped in occasionally. Larry Fagin and others. But the building’s long gone. There was also a little down-home Italian restaurant, Brunetta’s, on First Avenue. It closed at three in the afternoon. You could go in there and get a bowl of pasta fagioli, with a little green salad and a hunk of Italian bread and butter for $1.25. For decades some of us also frequented an Italian pastry shop between 10th and 11th on First Avenue, called De Robertis, which went out of business a year ago or so. It had been owned by the same family since 1903.

BLVR: The East Village has really changed.

RP: It’s become gentrified, more homogenous. There’s a lot more money here now, and a lot less crime. It’s a mixed blessing. I miss the old mom-and-pop businesses, the feeling that you might just be one step away from Europe. Almost all the greengrocers were Italian at that time, and there was Lupino’s fish market and Palermo Bakery. You’d go shopping the European way, not the American supermarket way. There was a store run by an old Eastern European woman who sold nothing but zippers and buttons. And then another one, Louie’s, with cardboard boxes piled to the celing, where you could buy children’s clothes very cheaply, like Orchard Street used to be. There was a funky grocery store on East 11th, run by an old man named, if memory serves, Gerardo. He sold Italian pasta for 19 cents a pound. And there was a little hole-in-the-wall store on First Avenue between 13th and 14th that carried nothing but butter and eggs. It was open only one day a week. Each week they brought in a huge cube of butter. You’d say, “I want a pound” and they’d cut it off for you and wrap it up in a piece of paper. I miss those places.

BLVR: Was there any particular opening or art show you remember?

RP: Lots. I remember Warhol’s opening for his Brillo boxes. I walked in and saw a brightly lit room with a pyramid of those boxes. It was stunning. I couldn’t believe how beautiful they looked. Andy gave me one later.

I remember a Frank Stella show at Castelli on 57th Street. Stella was showing paintings that were mainly in purple geometric patterns with white pinstripes. I walked in and immediately smelled grapes. I thought “Did he spray those with some special grape smell?” But he hadn’t. I guess it was some sort of hallucination I had, but I really smelled it. It was like Welch’s grape juice. Anyway, these are just two among many terrific shows. Fairfield Porter, Joe Brainard, Phillip Guston, de Kooning, Man Ray, the Art of Assemblage show at MoMA, on and on.

III. Coming to New York / Kenneth Koch / The Moon Over Paris

BLVR: What made you decide to come to New York to study?

RP: In the spring of 1960, an anthology was published by Grove Press that was called The New American Poetry 1945-1960. I already knew about most the poetry. As a high school kid in Tulsa I had subscribed to The Evergreen Review—I may have been the only subscriber in Tulsa—and to even more obscure magazines such as LeRoi Jones’ Yugen.

At that time I was interested in Pound, Rimbaud, the Black Mountain poets, and the Beats. I liked Ginsberg a lot, Ferlinghetti, and Corso. I went to Columbia partly because Allen and Kerouac had gone there. At Columbia, I was assigned to Professor Kenneth Koch’s Literature Humanities class, a two-semester required course in which you basically read great books of the Western world, starting with the Iliad and ending with Crime and Punishment. The class met three times a week for 50 minutes, I think. I quickly fell under Kenneth’s spell. He was a phenomenal teacher, engaging, serious, funny, interested, spontaneous, and very smart.

BLVR: And he used to jump on tables?

RP: I’m sorry to say I’m the originator of that story.

BLVR: You started that rumor?

RP: Yes. But it was only one time that he got up on his desk and sang a spontaneous aria to show us what Goethe’s Faust was really like. The translation we were reading was stilted and boring. Kenneth said you have to imagine what it’s like in the original German: an opera.

BLVR: You stood out to him…

RP: Well, maybe at first because as a freshman I wore cowboy boots and Levi’s. Very few people in New York in 1960 were wearing cowboy boots and Levi’s. Coming from Tulsa, I also wore chambray work shirts, I had sideburns, and I didn’t look like my classmates, many of whom dressed in suits and ties. I ended up taking three courses from him, and we became friends and then co-workers, teaching poetry writing to children. And we played a lot of tennis together. We traveled around the country and gave readings and went to Paris together. He was a wonderful mentor and father figure to me.

One night in Paris we had a great dinner at a restaurant he had heard about, on the Ile Saint-Louis. Afterward we walked up the Rue de Seine and then around the west side of the Luxembourg Gardens, which was closed at night. It was a beautiful evening, maybe in May. Kenneth stopped and looked up at the crystal-clear sky with a full moon, and he said, in the most wonderfully sincere, simple, open, unaffected way, as if he were talking to himself, “Isn’t this just exquisite?” That was a very moving moment for me, to see Kenneth so unguarded, because he was normally highly aware of whom he was with and what he was saying.

IV. Collaborators: Alex Katz / Jim Jarmusch / Yu Jian

BLVR: I’d love to hear about your work with Alex Katz.

RP: Alex doesn’t work one-on-one, simultaneously, with poets. As he once put it, “I don’t want poets messing up my images.” [Laughter] So I’ve worked with him in a slightly more distant way. For instance, we did a project called Light as Air. Alex sent me 13 preliminary charcoal drawings and I wrote something to go with them. He then refined his drawings into etchings. The whole thing was published as a portfolio, with the images on the right and the text on the left. The result was beautiful.

BLVR: Oh, who published that?

RP: Pace Editions ended up handling it. Originally it was going to be done by a Swiss publisher but that guy went out of business.

BLVR: There’s a long tradition of poets working with visual artists on these kind of folios.

RP: It goes way back. Many of the other collaborations I did were more immediate, hands-on, simultaneous. Like the ones with Jim Dine and with George Schneemann.

George lived for 40 years in the same apartment, an entire floor of a building on St. Mark’s Place. He used one room for a studio. I worked with him there many times over the years. It was so nice to be there, with all his materials—egg tempera, canvas, illustration board, various kinds and sizes of paper, acrylics, oil pastels, collage materials, brushes, glue, fixative, colored pencils, inks, and charcoal. The only thing we knew in advance was what materials we would be using. Sometimes we would pre-buy nice big sheets of paper at the nearby New York Central Art Supply. After that the work was totally spontaneous.

BLVR: Tell me about the collaboration with Jim Jarmusch. You’re probably tired of being asked about it, but you were both students of Kenneth at different times. How did you meet?

RP: We were invited to dinner at a mutual friend’s house. Jim is about ten years younger than me. That we both loved Kenneth helped us get along. I knew Jim was a well-known filmmaker, but I never imagined I’d meet him. My son was a big fan of his work and, in fact, turned me onto it.

BLVR: Which movie?

RP: Down by Law first, then Stranger Than Paradise. I’m not sure Jim had produced many other movies at that time. After that I followed his career but I never had occasion to meet him. We hit it off right away.

BLVR: Paterson came out last year. I read that Jarmusch asked you to work on it, and you said, “I can’t come up with any poems for this,” but in the end you did, right?

RP: Uh, something like that. I was sitting right over there talking to him on that phone. [Points to phone]. Jim had told me some years ago that he was thinking about of making a film about a poet, but that he would talk to me about it later. Several years later he called me up and said, “You know that film I talked about? I’ve been working on the the screenplay for it. Would you mind being the poetry advisor for the film?”

And I told him, “Of course I wouldn’t mind. I’d love to. I have no idea what a poetry advisor is, but yeah, whatever you want.”

I was honored to be asked. And then on subsequent phone calls he’d kind of nudge me closer to working more on it, and finally he said he’d found some poems of mine he’d like to use in the movie.

And I said, “Great, fabulous, go to it, wonderful.”

Then he said, “I’ll send the script over to you. Maybe you’ll feel like writing some new poems for it.” I was chilled with terror at the thought of doing that. And I said, “No, I don’t think so, it’s too much pressure, I can’t handle it.” He sent the script and I read it, and lo and behold I almost immediately found myself writing a poem in the persona of the protagonist of the film and over the course of the next day or two I wrote three more.

There are a lot of poems in that movie. Seven by me. A couple by William Carlos Williams. One by the little girl in the film, which was actually written by Jim himself for the movie. Also there’s the rap poem. So there are at least 10 poems in the movie, which must be a world record.

BLVR: Was that your first experience working on a movie in that way?

RP: No. Back in the 1970s I had worked with Rudy Burckhardt, the filmmaker, visual artist, and photographer . He was what used to be called an underground filmmaker. Fiercely independent, he conceived, financed, directed, shot, and edited his own movies, in 16 mm., using a little camera. The culmination of our work together was a film called City Pasture. Rudy is still underrecognized, even though he’s had retrospectives at MoMA etc. He’s really, really good.

BLVR: Any other collaborations?

RP: There have been quite a few. For example, with the French artist Bertrand Dorny I made 50 handmade books. And I wrote some poems with a Chinese poet…

BLVR: A Chinese poet.

RP: He speaks no English.

BLVR: When did you learn Chinese?

RP: I didn’t learn Chinese, though I can say a few things in it. I can say “I would like to have two glasses of beer.” But, no, I got to know him through co-translating his work with the Chinese-American poet Wang Ping, who asked if I would help her, because at the time her English was excellent but not perfect. Her Mandarin is terrific—she grew up in China. So I worked with her on a contemporary poet named Yu Jian. That got me interested in him. Years later she and I did a whole book of his work, which we published as Flash Cards. Eventually I had the chance to meet him.

BLVR: Really? Where?

RP: At a poetry festival in Sweden. And a few years later I saw him here in New York.

BLVR: What brought the chance? He was just traveling through?

RP: For some reason he was coming to America and I was the only poet he knew in New York, so I helped him get a reading at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project.

We had a great time one day going around New York together. He spoke no English, and at that time I knew three things in Mandarin: Hello, thank you, and chop sticks.

We’re so different. He’s a short, rotund bald-headed—well, I’m bald-headed too, but he’s really bald-headed—guy who had never been to New York, and we just walked around the city gesturing and speaking our own languages, and cackling on top of the Empire State Building. Then we ate a huge lunch in Chinatown. We had a lot of fun together. A few years later I got invited to a literary conference in China. A bunch of American poets went over: Waldman, Robert Hass, and Brenda Hillman, as well as the Slovenian poet Tomaz Salamun. Yu Jian was part of this conference, which was a terrific experience. After it concluded Yu Jian and I went down from Beijing to his hometown, Kunming, where we did a reading together and traveled around a bit. Kunming, not far from Vietnam, is a little town of about five million. Pretty small by Chinese standards! [Laughter] A few years later he invited me back to China. Throughout we’ve kept in touch by e-mail.

BLVR: But how?

RP: Google Translate.

BLVR: Ah, really? That’s so funny.

RP: We even wrote 15 or 16 poems together by e-mail.

BLVR: Through Google Translate?

RP: Yes, going back and forth. At one point he came back to America and did a residency in northern Vermont at the place called The Studio Center. He was up there for around three weeks, on kind of a retreat, but I happened to be in Vermont at the time so I palled around with him there. We wrote three new poems together, passing the paper back and forth.

BLVR: How did you know what you were writing off of?

RP: We didn’t. It was like the the old Surrealist game, the cadavre exquis. It was remarkable how unified the poems turned out. I think it was because we knew each other and we were in the same landscape—on Mt. Mansfield, high up in the morning fog. It was really exhilarating.

V. Ted Berrigan, Flossie Williams, & the Wheelbarrow

BLVR: I once heard a story about you and Ted going to William Carlos Williams’ house and asking his widow for cookies.

RP: No, we didn’t ask for cookies. Actually we were visiting our friend Joe Ceravolo in Bloomfield, New Jersey, where he lived with his wife and two children. Joe was a hydraulic engineer, helping design and maintain the state highways. Like Williams, he had a day job and wrote fresh and wonderful poems. Joe invited Ted and Ted’s wife Sandy and their young son David, as well as my wife and me over for dinner. When we got there there Joe’s wife Rosemary said, “Oh, I mistimed things, the dinner’s not going to be ready for another hour.” So Joe said, “Would you guys like to go see where Doc Williams lived?”

We said, “You kidding? Great!”

So we piled in the car and drove to the Williams house in Rutherford. We parked outside and looked at it and sort of vibrated for a while. Then Ted said, “Sandy, go knock on the door.” He didn’t have the guts to do it. I didn’t either. But Sandy was young and open, with a hippy kind of innocence, so she walked up and knocked on the door. It opened, and then she gestured to us to come on. Which we did, and standing at the door was Flossie, Williams’ widow—he’d been dead for a year or a year and a half—and she said, “Come in, make yourselves at home.” We stepped into the living room and sat down. After we had chatted for a few minutes, she gave us a little tour of that floor of the house. “Here’s Bill’s little desk and this was his special bookcase, and here’s a Charles Sheeler painting, always one of his favorites.” And here’s this and this and this. She was very sweet. When we got back to the living room she said, “Well, would you like some beer? Of course not the child, but the rest of you.” And then she brought out some cookies she’d made. It was pretty great. Actually, it was hard to believe we were there.

Oh, I remember one other detail. When we came out and started to walking back to the car, I turned around and looked at the house and the driveway, which ran alongside the house to the back, where there was a small garage. And I saw, back there, overturned next to the house, a red wheelbarrow. Of course it wasn’t the red wheelbarrow.

BLVR: How do you know?

RP: It was a metal one. The original one was wooden. But it was thrilling anyway.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.