Translations from the French by Mitchell Abidor

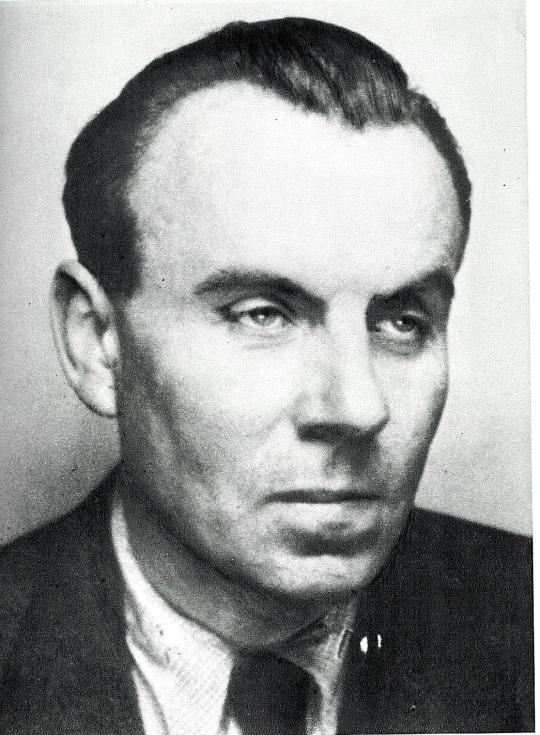

At the time of his death in 1961, French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline remained an extraordinarily controversial and contradictory figure. He had been a cavalryman in World War I who collaborated with the Vichy government during the French Occupation and was later found guilty of treason. He was a physician who treated the poor in some of the worst slums in Paris, yet who was also a virulent racist and anti-Semite. He was a disillusioned humanist who turned misanthropist after seeing a world overrun with stupid human brutality. He spread myths about himself, and publicly attacked those who repeated them as truth. He loved the ballet, he loved animals, and was during his lifetime perhaps the most singularly despised man in France—a role he accepted and performed with undeniable gusto. Some said he was the embodiment of evil, others that he was merely and utterly insane.

He was also one of the most important and influential writers of the 20th century. He smashed forms and rewrote the conventions of what constituted proper style and storytelling. Without Céline’s bitter, sprawling, phantasmagoric black comedies, there would have likely been no Henry Miller, no Beat movement, no Jean Genet, no Kurt Vonnegut, Nathaniel West, Hubert Selby, Thomas Pynchon, William Gaddis, or a thousand others.

So then the question becomes, given Céline’s undisputed literary importance, why does so much of his work remain unavailable?

In 2009, fifty-five years after its original French publication, Normance, the last of Céline’s twelve novels to be translated into English, was finally released for the first time. Mea Culpa, an attack on communism written after a brief visit to Russia in 1936, was translated and released in the States in 1938 but never reprinted. In 2012, a small Quebecois publisher released a limited edition of three notorious pamphlets (some would call them “screeds” or “rants”) written by Céline between 1937 and 1941. It was expressly forbidden to sell or ship the book outside of Canada. Apart from the novels and two minor works (a play and a collection of ballets), none of Céline’s other writings are available in English. The amount of untranslated material is staggering—thousands of pages worth of essays, speeches, and correspondence.

Yes, Céline was an unpleasant fellow with some mighty harsh and unpopular ideas, but I’m hardpressed to think of another writer of similar stature, no matter how loathsome we may find his or her opinions, whose work has been so effectively quashed. Contrary to general perception, it’s not that these works have been banned. They haven’t been, at least not in any official manner. People are simply afraid of them, it seems, in a way...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in