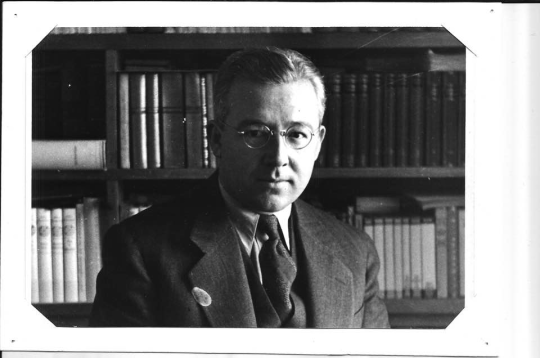

A self-portrait by Sabahattin Ali.

Kaya Genç on Sabahattin Ali’s Madonna in a Fur Coat

In 1938, at the height of Turkey’s single-party rule, three of the country’s four great writers were in jail. Two of them, the poet Nazım Hikmet and the novelist Orhan Kemal shared the same cell at Bursa Prison. They wrote poems and stories, translated and reviewed fellow authors’ works, and engaged in lengthy correspondence with the novelist Kemal Tahir, who was serving a fifteen-year sentence in another prison in Anatolia. They all agreed on the brilliance of the writings of their fellow author Sabahattin Ali, a thirty-one-year-old novelist and short story writer, who had done time at Sinop Fortress Prison (where most communist sympathizers were locked up) in the early 1930s. Ali had been imprisoned after lampooning several leading republicans in a poem he recited to a group of friends. After his release in 1933, Ali was forced to compose a poem full of praise for the same figures, so as to be allowed to teach at a state school in Konya, the Anatolian city where Rumi composed Mathnawi in the thirteenth century.

Hikmet considered Sabahattin Ali the leading Turkish fiction writer of the age. His first novel, Yusuf from Kuyucak, ridiculed the statist argument that there were no classes in the young Turkish republic; Ali saw signs of a class society everywhere, however passionately Turkey’s rulers denied its existence. Ali’s 1943 novel, Madonna in a Fur Coat, recently published in English for the first time by Penguin Classics, is also about noticing these things in New Turkey.

Madonna in a Fur Coat tells a story with a frame that some find even more interesting than the actual story. The main story follows a young, fragile Turkish man’s love for a charismatic German artist. The narrator of the frame story, meanwhile, is an unnamed twenty-five-old banker. The narrator is introduced to us after he loses his modest post in a bank (“I am still not sure why, they said it was to reduce costs”). Like Sabahattin Ali, he is a dreamy young man in love with books and is considered a failure by people whose cruelties towards the less fortunate he never fails to see.

Early in the book, as the narrator wanders among different ministries and companies in New Turkey’s capital, Ankara, to look for work, he sees numerous episodes of class division. While watching workers march alongside the façade of the People’s House, an official building of the republican regime, the narrator comes across an old classmate, Hamdi, now a successful businessman, who invites him to his house. With a few masterly brush strokes, Ali draws...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in