This is the third part of a series on lost landscapes by Stephanie LaCava. Read the first part here. Read the second part here.

Stephanie LaCava on Artistic Youth, False Geo-Tagging, and the Poetry of Aram Saroyan

Some time ago, I received a request over email from a young woman based in London. Her address did not contain a name, but a word I did not understand followed by the year 1990. She asked to interview me for a Chinese story on “Artistic Youth.” As she explained it to me, the term, call it AY for ease, speaks to a subculture that has gone through three phases in its Chinese incarnation.

Between 1912 and 1949, AY spoke out about feudal forces. In the 1980s, when China became a free market, AY were hopeful dreamers, writers who “wrote the country’s change, their experience and dreams into their works,” and became beloved by the nation. For many famous writers who came from working-class families and the army, the AY represented hope for the new political and cultural landscape. The third and most recent installment was not so promising. AY has become twisted, distorted, a kind of pretentious lifestyle. Of this last phase, she wrote:

It’s more about how to look like an AY rather than what it used to refer to. One of the reasons is that the growth of social media has allowed people to create an illusion about their life or personality online. Many young people pretend to be AY and present an image that is just emotional with no social capabilities or any contribution, making the society think AY are irresponsible with useless imagination. More and more people forget that the AY are supposed to be intellectual with profound knowledge on the fields that they truly love. Another reason is that in China most people are pursuing material achievement, they are utilitarian and tend to judge others according to their own value standards. Therefore being romantic and sentimental is undesired, and the work of literature and art seems to be devalued. Many young people have to give up their pride and dream under the pressure of the reality.

She mentioned she had read and loved a book of essays I’d done three years ago about growing up overseas, a self-obsessed, unwell teenage girl. Above all, it was the story of a very curious girl. We spoke on the phone and emailed a few times. The story appeared in a Chinese magazine. She discussed the changing landscape of AY, and how she is hopeful that this faction is coming back around to represent its older meaning. We unapologetically begin following one another on Instagram. I know it’s her, because she messages to tell me so.

Months go by and I post an image of my son wearing a tricolor sweatband, in the background, stacks of books. I false geo-tag it on Instagram (something which has become a signifier of another kind of subculture, a kind of trickster AY playing with faux-Bohemian irreverence. False, because, despite this demonstration not to play by the rules and post where we really are, we, too are still engaging online.) In this case, I chose the tag because I wanted it to say 5:30 am, when the day starts in my house. What I found read 5:30 with the Chinese letters 中正桥 just after.

After posting, I receive a few comments asking if I’m in China, and then a direct message from my interviewer asking if I’m in Taiwan working on my lost landscapes series. She had read the past two posts and seen images of the travels on my page.

Stephanie, just saw your post. Are you in Taiwan? Is it another follow-up about the old bridge there? I thought you were going to write about it as it somehow goes with the series you did before? When I read the first one, I thought you should check China and Asia. I’ve grown up seeing how tradition and culture are destroyed and twisted.

The tag turned out to refer to the location of an early morning run at the Zhongzheng Riverside Park. The Zhongzheng Bridge is located in Taipei. Once made of wood, it is now made of cement, concrete. It is in a controversial state of decay.

*

Last year, I realized I kept being drawn to writers who play with mark making, or at least are attentive to its powers much in the same way as visual artists. There was Eve Babitz (“I am really an artist, not a writer. So, I like the way Arabic numbers look un-written out on a page.”) And in a roundabout way, one of her boyfriends who featured her in his artist’s books, Ed Ruscha.

Ever the clever faux naif, Ruscha is renowned for playing with words: “I always looked at a word like it was a horizontal bunch of abstract shapes, which is really what it is…Words in horizontal lines are like objects lined up on a table and I’ve always liked still lifes.”

There was also, Clarice Lispector. The epigraph of her Agua Viva comes from the Belgian artist Michel Seuphor: “There must be a painting totally free of dependence on the figure-or object-which, like music, illustrates nothing, tells no story, and launches no myth. Such painting would simply evoke the incommunicable kingdoms of the spirit, where dream becomes thought, where line becomes existence.”

There are more on this list, like Cy Twombly and his playful misspellings and classical Greek allusions splayed on wildly abstract canvases.

Lately I’ve been intrigued by the reissue of Aram Saroyan’s Complete Minimal Poems. They are deceptively simple (the same goes for much of the aforementioned work) and in many cases, funny.

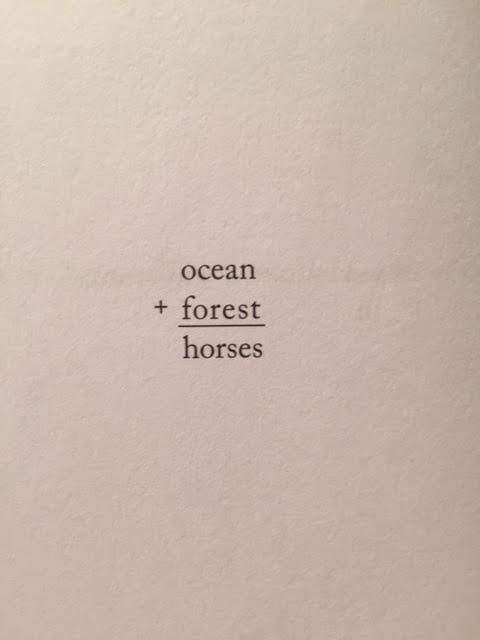

There’s:

A nod to two mythical landscapes and then, the animal riddled in cliches of lifestyle and running free. To keep these creatures outside of any sort of natural habitat is a wildly expensive endeavor.

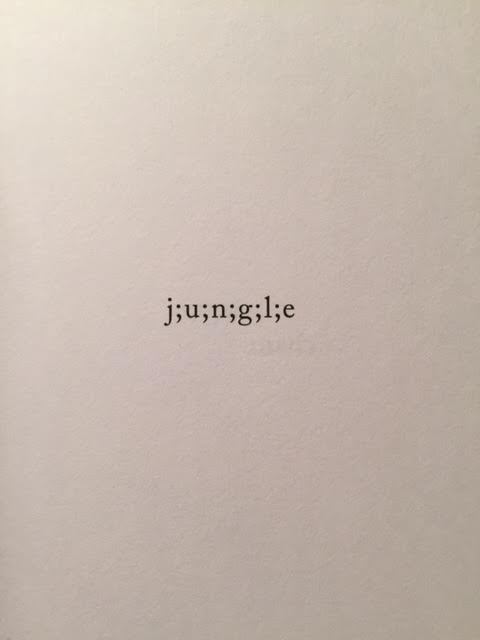

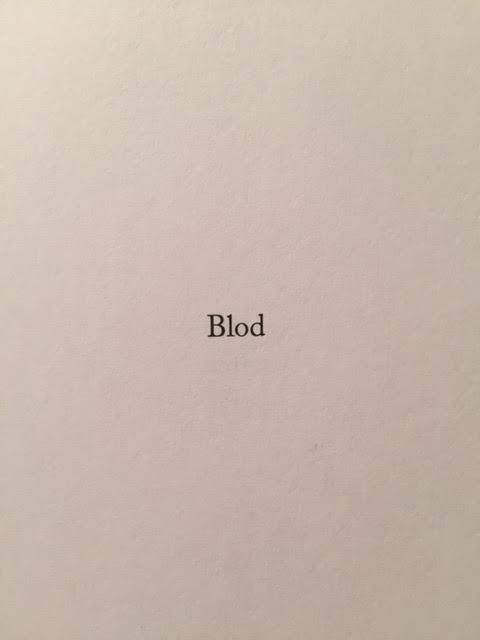

There are the one word poems, like:

Is another “O” missing? Or was the “L” added by mistake?

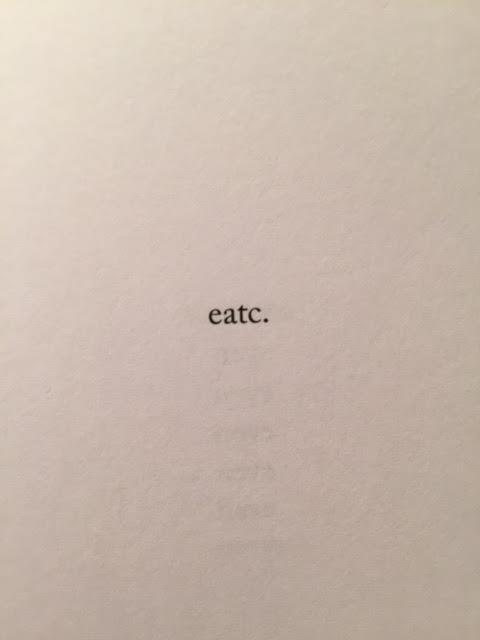

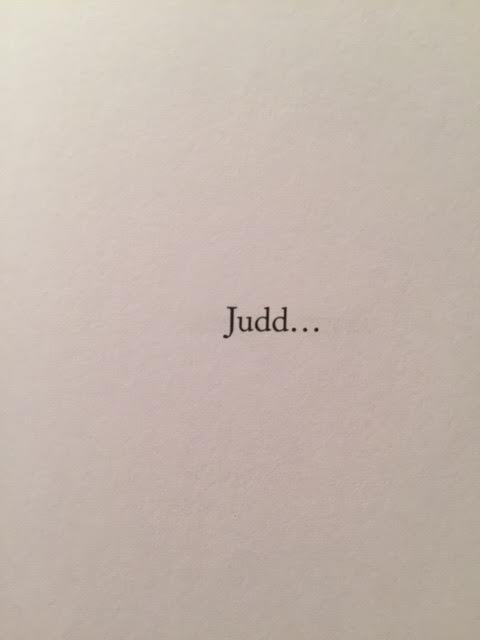

and even:

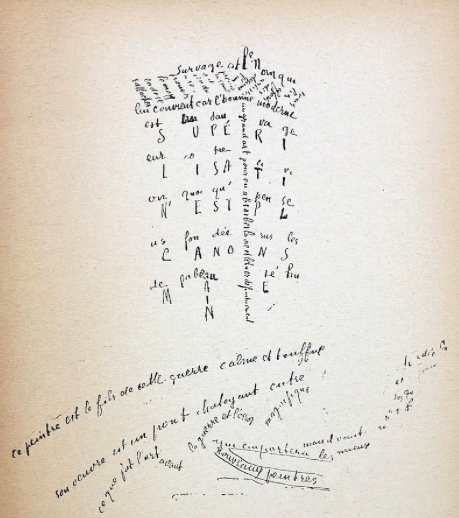

Saroyan’s work is often linked to Concrete Poetry, in which visual approaches are used to play with the meaning of the words. An earlier player was Guillaume Apollinaire with his Calligrammes: words sometimes even in the shape of a place. Concrete Poetry is less about typography, more abstracted topography on the page.

While Instagram is known as a social media platform for pictures, its etymology betrays the importance of the words involved: captions and geo-tags. It is from the Greek gramma, a picture, but one which is written, often involving characters, alphabet letters.

I email my interviewer from above asking her if I can use her name in this piece, explaining to her that I will quote from her note and messages. She tells me, of course, use Alison Yu. It is her pen name.

Initials: AY.