Daniela Franco on Meme Theft and Homicidal Adolescents on the Run

I.

Let me start by confessing that I am not entirely sure what a meme actually is. I don’t know how far removed the word as used in Internet culture is from Richard Dawkins’ original concept of cultural genetics. Is a meme an original unit that mutates slightly as it is propagated, like the subtitle parodies of the scene in Hitler’s bunker from Downfall? Or is it the original unit unvaried, but with a new claim of authorship at every reproduction? Either way, what is the ultimate aim of a meme?

Meme theft is common in Mexico: someone with few Twitter followers comes up with a witty image-text combination, only to have it retweeted and reclaimed by a mainstream “social entertainment company,” then indignantly re-reclaimed by a third party as his or her own creation. I can (roughly) understand how a media company monetizes thousands of retweets, but what’s in it for the regular meme appropriationist? Has a meme ever made a commoner rich or popular? More often than not, a meme’s authorship is seemingly devoured by its own virality.

Also common in Mexico’s conservative literary scene is plagiarist hunting. Every suspected writer is a plagiarist until proven an appropriationist, his work scrutinized until the origin of his dubiously authored quotes is found. Ostensibly the Internet reverses this witch-hunt process, thanks to altruistic meme-dissection websites like Know Your Meme. But who would want to know the real author of a meme anyway? Who is interested in the origin of the image or its original context? For all Mexicans care, this bewhiskered chub is just some sarcastic Mexican office worker, not Neil deGrasse Tyson.

The redundancy of the notion of authorship paired with diligent manual (digital) labor that has no purpose but entertaining the masses: it could be said that a meme, in the age of viral reproduction, is the quintessential act of appropriationism, the epitome of uncreative creation. Yet in experimental writing appropriationism often comes signed, and in contemporary art it often comes with a profit. An Internet meme is like a Richard Prince giving his work away for free.

Yes, most likely I am missing the point entirely. Imagine my surprise, then, to discover myself as a meme generator.

II.

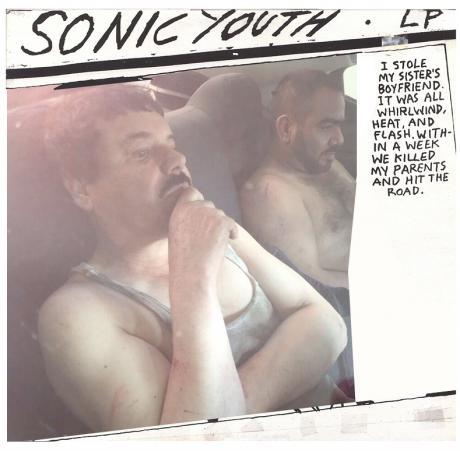

A few minutes after photos of the (most recent) capture of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán were published on Twitter, the artist Cuauhtémoc Padilla (@cupagu) posted a side-by-side image of the photo of El Chapo and his sidekick El Cholo inside a car and the cover of Sonic Youth’s 1990 album Goo. Formally and conceptually, the convergence was striking.

El Chapo and El Cholo are not only arranged in a fashion similar to Raymond Pettibon’s homicidal adolescents on the run; they also share an attitude of aloofness and melancholy. El Chapo and his friend are the poor man’s version of those teenagers, a Sinaloa corrido to Pettibon’s L.A. punk. It was an irresistible match. I had to complete and polish @cupagu’s discovery. Like many inspired by Lawrence Weschler, I too seek and archive convergences: a church designed by Sol LeWitt and a kids’ clubhouse in Oaxaca; a Bacchus door knocker and Melanie Griffith’s hairdo in Working Girl; Momus and Tancredi Falconeri; a Lucian Freud painting and the band Veronica Falls.

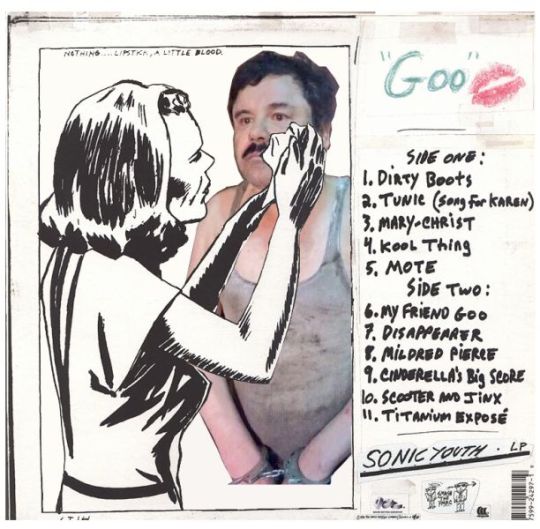

While looking for the original image to create a composite with the cover—I was aiming for a roughish collage, avoiding impeccability or the worn-out Goo parody—I discovered that other recent picture of El Chapo that was a perfect match with Goo’s lesser-known back cover: a woman cleans blood and lipstick from the face of a man as perplexed and petrified as El Chapo in that motel room. I Photoshopped both covers and shared them on Twitter with @cupagu, as well as a few others already following our thread.

After some sparse retweets, we thought we had reached the end of the joke. Never would we have guessed that a snobbish Twitter conversation with references to Aby Warburg’s pathosformel could be the origin of a viral meme. I later posted the photo to Facebook, where one of my 300 friends, the director of the Mexican gallery LABOR, took it and posted it on Instagram. As I’ve worked with record covers in the past, a friend asked, “Is that a new piece?” (A meme d’artiste, he later called it.)

Only 10 or 15 people had shared the photo on Facebook, but within a couple of hours it came back to my timeline transformed into a meme: a music journalist had shared it without knowing I’d made it. By the end of the day even Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth had caught wind of the meme through LABOR’s Instagram. Though LABOR had attributed the meme, Ranaldo—in accordance with meme protocol, I assume—reposted a rather exhausted copy of my cover, tagging Raymond Pettibon, and captioning his post “El Chapo Youth! Latest Goo variant. Reposted from… the Internet!”

The Internet! How humiliating!

“You should be proud, not offended,” a friend told me. “He’s called you God.”

III.

Even though memes are a widespread release for Mexican frustration with corrupt authorities, not many circulated involving the photos from this new El Chapo capture.[1] Someone joked that the Sonic Youth meme was so good that it stopped meme production altogether. (If only.)

I’d volunteer a couple of more plausible explanations, naive yet hopeful: that we are finally jaded, that we find the exploits of our government surrounding El Chapo’s escapes and captures less funny and more distressing. There is also the aesthetic and conceptual complexity of the aforementioned photos. The images surrounding his last escape were filled with all the unintentional humor of a banana republic. The two new images seem to present us with a novel-like story (probably false [2]) reminiscent of a cinematic aesthetic, of failed outlaws, outsider nostalgia—an aesthetic akin to Pettibon’s.

I exit the meme factory as mystified by its mechanics as I entered; what may seem obvious to meme-savants is still unfathomable to me. I only shared my images twice. Five days in, while even Kim Gordon had retweeted the cover, @cupagu had already forgotten all about it and gone back to work on a real project. But my friends are still in awe of me. “The Sonic Youth/El Chapo cover was you!? Wicked, it’s the first time I’ve met a meme creator.” Okay, then. If an accidental meme is to be the proudest accomplishment of my career, I shall milk it for all I can.

“The only meme is an accidental meme,” Kenneth Goldsmith wrote to me last Sunday. “Like chanterelles, you really can’t grow them. They have to grow themselves.”

[1] Though shortly thereafter Sean Penn unleashed a new batch of memes as seemingly endless as his Rolling Stone piece.

[2] El Chapo had actually escaped from the Marines and was captured by federal police who didn’t know who he was—again not unlike Pettibon’s couple, who weren’t homicidal runaways but witnesses to the Moors murders on their way to court.