Ratik Asokan on Revolutionary Japanese Photography from the 1960s and Contemporary Urban Life

In June of 1968, Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki helped curate 100 Years: A History of Photographic Expression by the Japanese. 100 Years was a seminal exhibition. Comprising over 1,640 photographs, and the result of three years of intense research, its aim was to define a definitive canon of Japanese photography. To this extent, the exhibition was a success. 100 Years helped bring photography to the front of Japan’s cultural consciousness, and it also unearthed countless previously unknown photographers. But Nakahira and Taki weren’t satisfied.

Contrary to the titular suggestion, 100 Years largely featured documentary photographs, so much so that it seemed to be arguing that Japanese photography was a craft of kiroku (recording) not an art of hyogen (expression). Nakahira and Taki respected this approach, but the more time they spent studying it, the more they realized that it wasn’t suited to depicting modern Japan. And so they decided to establish a new tradition. In November of 1968, Nakahira and Taki published the first issue of Provoke, a short-lived but enormously influential magazine that showcased the first wave of experimental Japanese photography; photography, that is, which had never been seen in Japan before.

Provoke pioneered are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus), a style diametrically opposite to 100 Years’ documentary realism. Are-bure-boke questioned whether realism was possible. “Just one centimeter from the photographer’s reality,” Nakahira wrote, “is another reality beyond our imagination.” And responding to this provocation, a generation of photographers set out to reveal the artificial processes of their medium; and, through this self-referential act, allude what was beyond. Increasingly, this meant taking call ‘anti-photographs.’ While realists searched for symmetries and beauties, the are-bure-boke photographers took chaotic shots. They tried random triggering, they shot into the light, they prized mis-shots and even no-finder shots (in which no reference is made to the viewfinder). This represented not just a new attitude towards the medium, but a fundamental new outlook toward reality itself. If realist photographers, as Teju Cole puts it, partook in a “mysteriously precise collaboration with the world;” are-bure-boke photographers fought with the world, or sought to expose it.

Daidō Moriyama, perhaps the greatest are-bure-boke photographer, captures its aesthetic in an autobiographical statement:

My approach is very simple—there is no artistry, I just shoot freely. For example, most of my snapshots I take from a moving car, or while running, without a finder, and in those instances I am taking the pictures more with my body than my eye… My photos are often out of focus, rough, streaky, warped etc. But if you think about I, a normal human being will in one day receive an infinite number of images, and some are focused upon, other are barely seen out of the corners of one’s eye.

It’s true that our visual experience is chaotic, but isn’t art, as Robert Frost once wrote, supposed to represent “temporary stay against confusion”? And is Moriyama’s practice even an art? Anyone with a camera can run around making pictures, and anyone with pictures can traffic ideas about life. Being suspicious about are-bure-boke and its aesthetic are totally valid, but after spending a little time at Japan Society, where are-bure-boke work of Moriyama and other Japanese photographers is on display, my mind changed. In theory, are-bure-boke is no more than an interesting idea. But these photographs transcend their process to become very moving, very scary works of art.

….

Lke any important formal innovation, are-bure-boke was originally conceived as a sociopolitical response. The 50s and 60s were decades of rapid and reckless economic development for Japan. It was a period in which the country tried to overcome the destruction and humiliation of World War II by embracing the consumption-centric western model of growth. Whatever the monetary success of this approach, there were also darker social impacts. Locals felt isolated by the sprouting consumer enclaves that held no connection to traditional Japanese culture; and rapid physical growth (tall buildings, etc.) could make corporeal reality itself feel unreal. “In these volatile times,” Nakahira wrote in Provoke’s iconic manifesto, “language loses its material foundation, that is, its reality, and floats in the air.”

T.S. Eliot famously called for poets “to dislocate if necessary, language into [their] meaning.” Nakahira could be speaking for any part of the 20th century. But viewed from the present, there is something particularly affecting or familiar about 60s Japanese photography. It represented a first response to the sudden and unforeseen arrival of hyper-economic development; and the power and sensitivity of this response has allowed it to transcend its time. The ideas seem to have capture something essential about the entire project of modern urbanity itself.

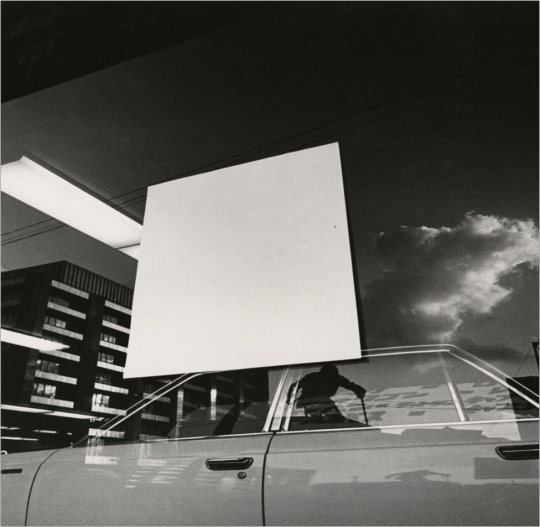

In Gallery For No Space, for example, Kiyoji Otsuji presents a palimpsest of uncertain and coexisting realities on a glass storefront. We look into commercial store, but other than a tubelight hanging strangely in the reflected sky, we can’t see anything that’s inside. A blank poster with its back facing us is placed right at the center of the shot, an ironic statement about the fact that we are on the outside of both the store, and the photograph. What we can see is a car parked on the street, a modern building; clouds, overhead telephone lies, two warped shadows of the same man painting a billboard: all of which come together on the same liquid surface of reflection. But the photograph isn’t about objects. Otsuji is channeling a sensation that many modern city-dwellers are familiar with: at some part of the day, as we walk past buildings or take a train across the river, our guard drops, and we become aware, even for a brief moment, of how ignorant we are about the city’s larger operations. It is a terrifying and lonely moment, but the moment that turns poignant with Otsuji’s eye. Despite its dark subject matter, Otsuji’s photograph has the otherworldly allure one associates with a Wallace Stevens’ poem.

Kiyoji Otsuji, Gallery For No Space

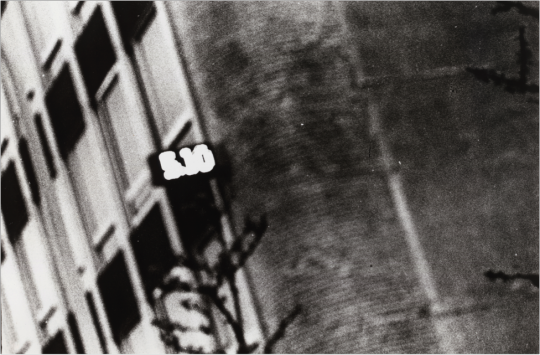

Are-bure-boke dealt with isolation and disorientation, but by eschewing this consolation of beauty, they turned these emotions into something altogether more rabid and terrifying. Consider this photograph from Daidō Moriyama’s book, A Farewell To Photography.

We are looking at the corner of a building that houses some sort of business (I am going by the digital sign). But Moriyama’s photograph is so unclear that you could convince that it is just about anything. In fact, the photograph’s real subject seems to be visual chaos itself—which doesn’t make it merely chaotic. Moriyama has cleverly framed this photograph: the building’s disparate surfaces grow out of its corner, and our eyes stretch in opposite directors in pursuit of them. This visual tension is only accentuated by the general tilt, suggestive of some collapse, of the whole photograph. What finally results is a compelling vision of chaos. In real life, our eyes simply skim over the unfolding visual chaos of visual reality. But faced with Moriyama’s photograph, we stop to drink it in.

Daidō Moriyama, Untitled 1

What’s important is that the chaos is distilled, but not redeemed. In fact, what we have is the opposite of redemption: accusation. The building can’t be remembered for it was never seen; the photograph can’t be beautiful because it doesn’t value its subject. Instead of artificially slowing down the city, and placing it on a canvas of beauty like so many other flânuers, Moriyama has focused on the internal frenzy that prevent us from appreciating the surrounding beauty. He is rubbing our faces in distilled chaos; he further blurs our vision, and doesn’t clear our eyes.

Flipping through many such photos—Moriyama was a prolific author of chapbooks—I felt myself descending into all-too-familiar, and all-too-disturbing world of sensory perception. The blurred digital signs, the dimply perceived humans, the pervasive of being bombarded by rather than soaking in, reality. This is precisely what gives these photographs their present political power. The bleak shock of recognition I felt when I saw these photographs meant that each time I visited Japan Society, each look has provided me with fresh insights into my engagement with the visual world.

Not all the insights have been bleak. For example, one Sunday I left the exhibition to find myself before a large group of Pakistani demonstrators. It was a large and boisterous group, and yet, their actions felt slowed down and neatly dramatized for my eye. This is probably because I just spent a good half an hour staring at Protest, Shōmei Tōmatsu’s iconic photograph of a stone-throwing student.

One of the major curators of 100 Years, and perhaps Japan’s foremost post-war photographer, Tōmatsu has had a long and wide-ranging career that featured a variety of styles. Tōmatsu never published in Provoke but he went through a brief are-bure-boke phase in the 60s, and Protest, taken in 1968 is a photograph that acknowledges this influence and but also transcends it. On one hand, Tōmatsu’s crisply and dramatically captured student represents the best of documentary realism. On the other hand, the student is surrounded by intentionally overexposed light that hints at a larger metaphorical chaos.

And this mixture—the familiarly human and the pervasively chaotic—best captured my experience of looking at the Pakistani demonstrators on East 47th street when I left the exhibit. Perhaps it’s even a good description of contemporary urban life itself.

Shomei Tomatsu, Protest

Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography will run at the Japan Society until January 10th.