Ratik Asokan on Revolutionary Japanese Photography from the 1960s and Contemporary Urban Life

In June of 1968, Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki helped curate 100 Years: A History of Photographic Expression by the Japanese. 100 Years was a seminal exhibition. Comprising over 1,640 photographs, and the result of three years of intense research, its aim was to define a definitive canon of Japanese photography. To this extent, the exhibition was a success. 100 Years helped bring photography to the front of Japan’s cultural consciousness, and it also unearthed countless previously unknown photographers. But Nakahira and Taki weren’t satisfied.

Contrary to the titular suggestion, 100 Years largely featured documentary photographs, so much so that it seemed to be arguing that Japanese photography was a craft of kiroku (recording) not an art of hyogen (expression). Nakahira and Taki respected this approach, but the more time they spent studying it, the more they realized that it wasn’t suited to depicting modern Japan. And so they decided to establish a new tradition. In November of 1968, Nakahira and Taki published the first issue of Provoke, a short-lived but enormously influential magazine that showcased the first wave of experimental Japanese photography; photography, that is, which had never been seen in Japan before.

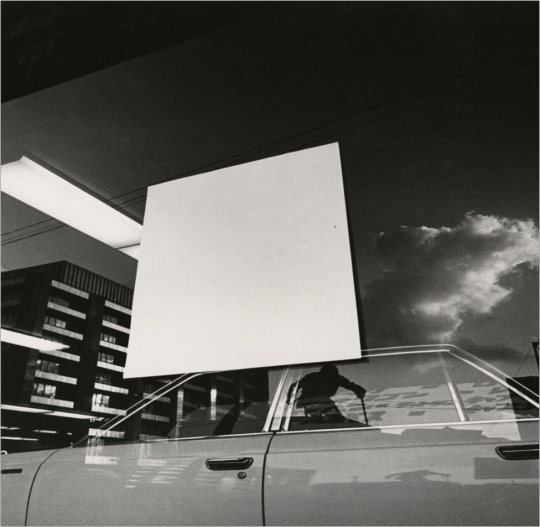

Provoke pioneered are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus), a style diametrically opposite to 100 Years’ documentary realism. Are-bure-boke questioned whether realism was possible. “Just one centimeter from the photographer’s reality,” Nakahira wrote, “is another reality beyond our imagination.” And responding to this provocation, a generation of photographers set out to reveal the artificial processes of their medium; and, through this self-referential act, allude what was beyond. Increasingly, this meant taking call ‘anti-photographs.’ While realists searched for symmetries and beauties, the are-bure-boke photographers took chaotic shots. They tried random triggering, they shot into the light, they prized mis-shots and even no-finder shots (in which no reference is made to the viewfinder). This represented not just a new attitude towards the medium, but a fundamental new outlook toward reality itself. If realist photographers, as Teju Cole puts it, partook in a “mysteriously precise collaboration with the world;” are-bure-boke photographers fought with the world, or sought to expose it.

Daidō Moriyama, perhaps the greatest are-bure-boke photographer, captures its aesthetic in an autobiographical statement:

My approach is very simple—there is no artistry, I just shoot freely. For example, most of my snapshots I take from a moving car, or while running, without a finder, and in those instances I am taking the pictures more with my body than my eye…...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in