A Review of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, By Haider Shahbaz

Hip-hopgave birth to an aesthetic that combined the concepts of

disruption and flow. Pioneering artists of the Bronx created rhythms that

flowed with ease while at the same time interrupted and broke open songs to add

layers and counterpoint to the ongoing emulsion of sound. DJs paused their cassette

players and rewound the beat multiple times to make breakbeats and record the

perfect breakdown. Early rappers had a stop-go technique—with sharp falls

between the bars/verses—that’s testament to the ubiquity of these breakbeats. Hip-hop

eschewed the values of harmony, synthesis, and climax—characteristics that provide

the basis for most forms of Western music, instead using loops, repetition, and

breaks to create a unique and contradictory style.

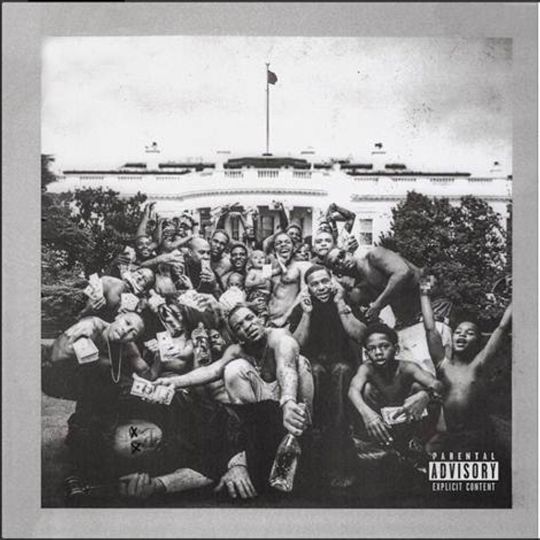

Kendrick Lamar’s new album, To Pimp A Butterfly, is a fitting tribute to hip-hop’s commitment to

disruption and flow and with the split makes for a layered interrogation of

society. Even on the cover art, the album’s disruptive intent is clear: a group

of jubilant black men and boys, including Lamar himself, stand on the lawn,

interrupting the view of the White House. The album seems to be taunting the

monolithic, homogeneous global order that works so hard to civilize, surveil,

and assimilate all dissent and difference.

The opening track, “Wesley’s Theory,” is a compendium

of clashing elements from the archives of Black diaspora culture. The title is

a reference to Wesley Snipes’ unsuccessful attempts at employing tax protestor

theories to save himself from imprisonment. The song begins with the crack and

hiss of vinyl, the beginning to a sample of the Jamaican Boris Gardiner singing

the heavy-funk anthem “Every Nigger Is a Star,” from the 1970s Blaxploitation movie

of the same name. Before the listener has a chance to settle into the sample, the

legendary Parliament singer George Clinton, interjects with an emphatic “Hit

me!” and the beat swiftly breaks into producer Flying Lotus’s psychedelic-jazz

arrangement, backed by horns and alto sax from Terrace Martin. And as if it

wasn’t enough to squeeze the vastly different Snipes, Gardiner, Clinton, and

FlyLo into the same song, Kendrick cuts the song midway through with a recorded

voicemail from Dr. Dre over a splat of cosmic chords that sound something like

Sun Ra’s lost tapes. After an upbeat outro, “Wesley’s Theory” gives way to a

sax cry reminiscent of Miles Davis’s flirtations with free jazz which opens to

the “For Free? Interlude,” a rap that sounds like a sped-up version of Ginsberg

or The Last Poets, accompanied by sparse and textured piano keys.

The spirit of disruption, the same break-and-flow

methods that define “Wesley’s Theory” and “For Free? Interlude” are spread

throughout the album. Despite the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in