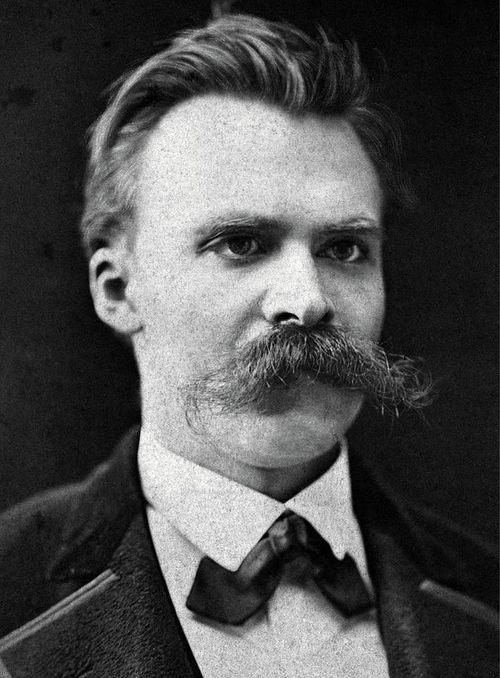

On Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo

1.

A few years ago, I was riding my bike and thinking about the declaration “I am not a man. I am dynamite,” when I hit a pothole and flipped over my handlebars, giving a new meaning to having one’s view of the world turned over by Nietzsche. The self-anointed Antichrist never wanted to be made a holy man (sooner even a buffoon, he said) and I won’t conscript him here except as, of all things, a contemporary memoirist. Ecce Homo,the mostly forgotten autobiography in which the dynamite explodes, is a downright archetypal if extremely odd memoir. The book’s subtitle, How One Becomes What One Is, nearly saysit all: this is a story not of a life but of a self in time—how the I of the

story became the I who tells the story—and like so much of Nietzsche’s writing,

Ecce Homo was, as he said, a hundred

years ahead of its time.

Nietzsche had no way of knowing, when

he wrote the text in three weeks in

the fall of 1888, that he was about to take ill or that Ecce Homo would be his final work. At the time he was mostly

ignored, and had been best known as a former philological wunderkind. His

status grew under his sister’s careful management during the insanity of his

final decade when he was unable to appreciate it, but she withheld publication

of his own self-reflections until 1908, eight years after his death.

Ecce

Homo remains a kind of lost book from a found author; in the century since

its publication, while Nietzsche has risen in prominence and fluctuated in notoriety,

Ecce Homo has remained relatively

obscure. While books like The Birth of

Tragedy and Thus Spoke Zarathustra

are frequently referred to (if less frequently read), Ecce Homo most likely sits on your shelf only as the unfamiliar

text included in the volume of The

Genealogy of Morals you were assigned in college.

If you go to your bookshelf now and

crack that 1989 Vintage edition to page 202 you will encounter Walter Kaufmann

of 1966 making the case for Ecce Homo by

comparing Nietzsche’s—can I say swagger—to

that of his contemporary Van Gogh (“the lack of naturalism is not proof of

insanity but a triumph of style”). We have Kaufmann largely to thank for the

redemption of Nietzsche’s name after the Nazis’ attempted appropriation. But I

don’t think it’s enough to read him only as a thinker but also as, perhaps, a

liver. Because life for Nietzsche was both...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in