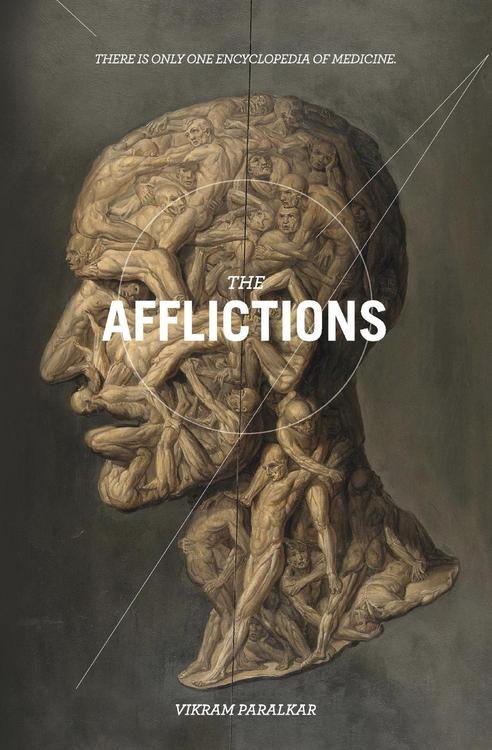

A Review of Vikram Paralkar’s The Afflictions

Disease is made into something new and strange through the eyes of writer-scientist Vikram Paralkar. In his debut book The Afflictions, Paralkar takes advantage of long held associations of medicine with magic to literalize our most darkly-held superstitions about illness.

The book claims to be a collection of entries from the fictional Encyclopedia of Medicine, a compendium of surreal and arcane materia medica. But behind the pseudo-medieval setting and the Calvino-style diction is a meditation on the symbolic resonances of the word “affliction.”

In one of the entries, a man afflicted with Corpus ambiguum can no longer understand the boundary between his body and the rest of the world. “On being asked to sketch pictures of themselves, invalids with this condition often draw incomplete versions of their own bodies, surrounded by amorphous auras and clouds of disjointed appendages.” A woman diagnosed with Persona fracta, on the other hand, is “unable to think of the ‘she’ who walked and the ‘she’ who spoke as the same individual.”

Haltingly, slowly, another story emerges from these encyclopedia entries. The framing narrative and the heart of The Afflictions is the story of Máximo, a young apothecary who wants to become a librarian. As he is guided through the workings of the vast “Central Library” by an elderly librarian, more and more bizarre medical entries are presented to the reader. In one of the more masterful narrative strokes in the book, the nature of Máximo’s own affliction is never fully explained but merely hinted at, mirroring how the encyclopedia itself only hints at the full scope of maladies that can potentially afflict us. As the elderly librarian warns Máximo, “If you read the Encyclopaedia from beginning to end, you get the feeling that every affliction known to man is part of a single, infinite progression. Or that every disease is a different facet of one great and terrible malady.”

If all this reminds you of a certain Argentinian short story writer, it should—Paralkar cites Jorge Luis Borges as his literary idol. The prose of The Afflictions at times can read like an imitation of Borges’, and Paralkar shares with Borges a collector’s delight in details. One can practically feel Paralkar luxuriating in the task of describing some of the three thousand essences of sounds distilled for the treatment of Agricola’s disease, “some that restore the invalid’s ability to hear the wings of sparrows, others that cover the lower sonorities of dulcimers, yet others that are concerned with the sounds of raindrops.”

But Paralkar’s obsession with minutiae and the archaic are more than just literary mimicry. The medieval world of The Afflictions is a vast, senseless universe that can only be ameliorated by fleeting beauty and small joys. For example, in the unlucky towns afflicted by Auditio cruciablis epidemics, every sound inflicts the most excruciating pain. Though the inhabitants are trapped in the desolation of silence without end, they respond not scientifically, by searching for a cure, but aesthetically, through dance. The medical scholars “write with wonder of the elaborate ballet of the people, the slow, viscous movements they conduct with wary grace, the extraordinary steps they take to preserve the silence.”

In The Afflictions, disease is an organizing metaphor through which Paralkar explores the unfairness of “affliction.” Why, he seems to ask, does one man wake able to prophesy in tongues, while another is fated to constantly regress to a state of infanthood? And if pure randomness is the only reliable authority in the universe, is there a way in which we can “cure” the affliction of chance? The Encyclopedia is one such attempt at a cure, where scholars try, impotently, to rationalize the irrational. As the elderly librarian warns Máximo: “One day, I fear, the separate strands will refuse to twist together anymore. The golden thread will unravel. The stacks out in the corridor will overflow the Library and become impossible to curate. The Encyclopaedia will lose its authority, and all our knowledge will disperse into fragments.”

The most poignant responses to the afflictions of chance are the moments of futile defiance. The entry on Lanfranco’s Disease tells of a village whose inhabitants became deaf to all except fragments of music only they could hear. Musical experts quickly realized that the afflicted were hearing, “A vast and magnificent expanse [which] could now be glimpsed, one without beginning or end” and yet the nature of the disease meant that it would be impossible to ever fully capture the music in its entirety. They try anyway, even though the passing of the years means that “The possibility of access to the music has dwindled to a handful of threads. Soon it will diminish to a trio, a duet, a solo.” The act of attempting to grasp what one can from inevitable loss, Paralkar seems to express, is the only human course of action, and the principle has no small resonance for the field of science as well.

The Afflictions returns us to the idea of the essential interconnectedness of mind and body, that our faculties of memory, of language, of morality, of love, are no less real and necessary to survival than the organs of the heart or kidney or lungs. Paralkar suspends, for a brief moment, the enmity between life and sickness in order to imagine how affliction can be a kind of sea-change, a shift in our being or impetus for a new mode of consciousness. A number of the diseases in the book ultimately result in victims having to become traveling minstrels or drifters. Their estrangement from any community transforms them into living ghosts, an analog to the death that is the consequence of many real-life diseases.

One such invalid, afflicted by Morbus geographicus, is forced to wander the earth endlessly, “becom[ing] a palimpsest, his life etched with layer upon layer of new scenery, until he wonders if there is anything beneath it all.” The hulking Encyclopedia of Medicine is similarly “over-written,” and threatens to lose all sense. But if we are meant to take any consolation from The Afflictions, we can take it from this, that just as the “trajectory” of the man suffering from Morbus geographicus inevitably “folds in on itself and leads him back to the land of his birth” so will our knowledge return to purer incarnations as it unravels.