Ann DeWitt on Annie Leibovitz’s Photographs of Susan Sontag

In Greek mythology Proteus was able to change shape with relative ease—from wild boar to lion to dragon to fire to flood. But what he found difficult, and would not do unless seized or chained, was to commit to a single form, the form most his own, and carry out his function of prophecy.

— Marvin Israel, Birthday Card to Diane Arbus, 1971

In 1973, Susan Sontag said of the nation’s increasing obsession with photography, “Kodak put signs at the entrances of many towns listing what to photograph.”[1] Sontag’s own life could have populated a town and had its very own sign. But in 1973, America’s focus was on other landscapes. As Sontag notes in On Photography, photographers, laymen and otherwise, were capturing images of a once hidden middle-America through the scope of the photographic lens. The American family was embracing the photo album with a catholic philistinism, reclaiming Nature as well as the nature of time in a “program of populist transcendence.”[2] It had been that way, says Sontag, ever since the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, when the camera rode the rail West. Like so many of Sontag’s essays on aesthetics—rife with literary comparisons and insistent on bridging the gap between literature and the “craft based arts”—here Sontag stakes photography’s evolution with Whitman: “Nobody would fret about beauty and ugliness, he implies, who was accepting a sufficiently large embrace of the real, of the inclusiveness and vitality of actual American experience.”[3] “The United States,” Whitman offered, “themselves are essentially the greatest poem.” Sontag interprets the work of Walker Evans and Diane Arbus through a similarly optimistic intersection: “All facts, even mean ones, are incandescent in Whitman’s America—that ideal space, made real by history, where ‘as they emit themselves facts are showered with life.’” It was photography’s job to demystify the ordinary lives people already led behind closed doors.

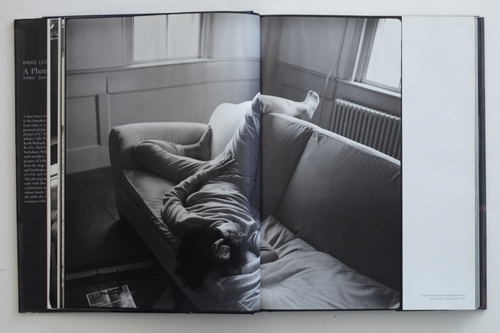

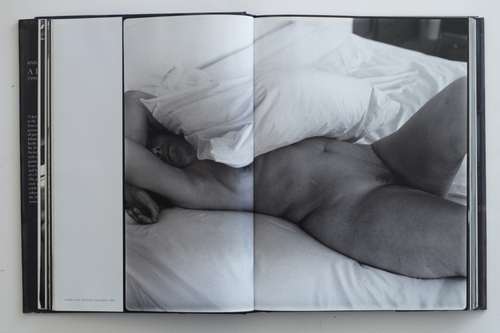

West 24th Street, New York. 1993

(While reading Sontag’s description, I picture an executive from Kodak erecting signs in front of various hangouts in a town in the Midwest, circa 1950. Red pickup trucks. A dog named Dan in front of a diner. A 24-hour store called “Stewart’s,” with a sign in the window advertising a special on Cream Soda and liter bottles of Tab.)

In an article for Artforum after Sontag’s death, Hal Foster said of Sontag’s desire to connect the aesthetic and the moral, “What could be more Arnoldian than her seriousness?”[4] For a moment, I think he is right. Sontag was a great annotator of dangerous ironies. “In the form of a photograph, the explosion of the A-bomb can be used to advertise a safe,”[5] she once said. And yet as I look at the photographs of Sontag taken by her partner and co-icon, Annie Leibovitz, on their last trip together to Paris—Leibovitz stopping to capture Sontag’s face smiling up at their new apartment overlooking the Seine—I wonder if Sontag wasn’t a bit more fun than all that.

“Susan’s favorite book as a child was Richard Halliburton’s Complete Book of Marvels,” Leibovitz tells us in her Introduction to A Photographer’s Life, a book commemorating the 2006 Leibovitz retrospective held at the Brooklyn Museum whose best photos, arguably, were of Sontag. In a rare moment of candid reflection on what was once publicly considered their enigmatic relationship, here Leibovitz captures Sontag in a single word. “Discovery,” she says. “[Susan] knew so much, but she always wanted to find out about something she didn’t know before. And if you were lucky, you were with her when that happened.”[6]

I picture Sontag’s face as she discovered the Roman amphitheatre, the Etruscan sarcophagus. Red pickup trucks. Stewart’s. Liter Bottles. A dog named Dan.

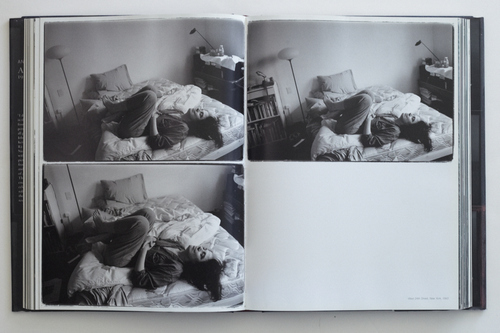

Sontag with Peter Perrone, Giza. 1993

*

I make the trip to the Brooklyn Museum to see the Annie Leibovitz exhibit three times over the life of the show. I go to see her photographs of Susan. I go on Fridays, heralding the weekend’s freedom with dog-eared copies of Illness as Metaphor, On Photography and a cup of tea from the bakery on the corner. The tea is weak; the bakery is a chain. The woman at the coat check at the museum asks me if I would like to check my bag; these books, she seems to imply, might be heavy.

It is odd, this journey. Ostensibly I am going to enact a visitation. I suppose I am not alone here. This is the draw of entering a museum: to travel to an untrespassed space where one can quietly, and without embarrassment, look outside of themselves. Often, this alone is enticing. Yet, each time I make this specific journey I returned with some satisfaction left wanting. I go to encounter something lived and yet a spirit still livid amongst us. To glean some authentic impression of this woman, this writer, whose ideas have sprung loose some screws in my head. (I would later learn Sontag had owned an apartment at the end of the block where I too had holed up in a studio—really, more of a renovated equipment closet with a windowless bathroom, an airport sink and a single window with a view on the Hudson—to write my thesis. How this instilled false dreams of having passed her on the street, I won’t detail.) My insistence on this encounter of Leibovitz’s photographs of Sontag after her death is beguiling, as the series of snapshots on view are meant less to memorialize the significance of Sontag’s written life than to capture the impressionistic—and often lonely—nature of her travels and discoveries. It is striking where light casts shadows around a room.

*

You can’t say more than you see.

Thoreau

The first time I go to see Susan, the 2 train to Brooklyn from my studio on the Upper West Side is diverted. There is construction on the Brooklyn Bridge. The Express train stops at Chambers Street. To get to Flatbush, I have to take a bus from South Ferry to the 4,5 at Bowling Green. My mind recalls a memory of Latham, NY, 1985. My grandmother, Hazel, is narcoleptic. Her license was revoked in the early 50’s when she nodded off once on the interstate. Afraid of falling asleep at the wheel, Grandmother travels through her domestic life in rural New York by taking a yellow cab through the quiet, suburban upstate streets. On one of her outings, she finds a stray dog in the back of a parking lot. She names the dog Boy as it is the first thing that occurs to her. Each evening she fries him up a mash of ground hamburger and Dole’s frozen peas, on the stove, in a 10-liter saucepan. She tosses the meat onto the pan like a Frisbee from the counter where her tape deck is playing Elvis, listens to hear the grease sizzle to be sure she’s turned the burner up high, dials Harry at Red Cab and invents somewhere she’d like to go.

By the time Harry arrives, Grandma has applied her lipstick and spritzed her hair with a blanket of Aquanet and donned her fur coat. For me, she dabs a drop of White Musk behind each ear. Harry delivers us to Woolworths, to Stewart’s, to Toys “R” Us and the arcade. On the way home, we stop at the Price Chopper for Kool-Aid and ham. We insist we are traveling abroad in a coach touring the Continent, as we watch the quiet contours of suburban New York in the early eighties go by from the backseat of an old, yellow cab.

*

Appetite is supposed to be immoderate.

Susan Sontag

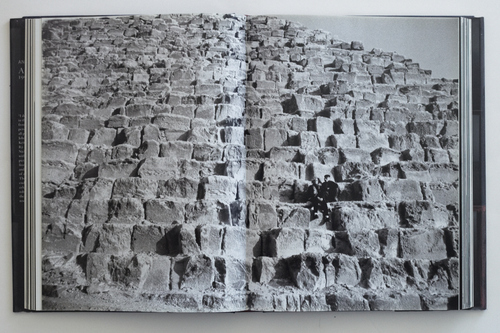

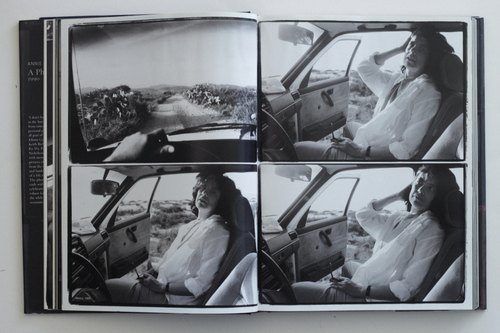

Photograph: Mexico, 1989. Leibovitz’s image is a series of four snapshots. Together, the four images recall the panes of a window. The first photograph in the series was taken through the windshield from the vantage point of the driver behind the wheel of a car. Up ahead, a myriad of cacti and scrub brush empties out into a long stretch of endless, dirt road. At the base of the picture, the driver’s left hand is visible gripping the wheel. In the three other photographs in this montage of Susan in Mexico, the car is stationary, pulled over onto the side of the road. The doors are thrown open and Sontag straddles the passenger seat, one leg on the floorboard of the car, the other already out-the-door and onto the dirt path, a black watch on her wrist and a pair of sunglasses in hand. Sontag is primping herself for the camera. Her shirt is unbuttoned. She leans back against the faded fabric of the seat. The image radiates a palpable heat. The photos are taken at close range. The intimacy between the two women is immediate. Leibovitz is in the driver’s seat with Sontag beside her. The photos capture the movement of Sontag’s arm as she reaches up to run her fingers through her hair. The movement of her arm is almost coquettish. It displays the coarseness of appetite. The remembrance of hair.

Memory: Latham, NY, 1984. In a little girl, there is a love for the body of Woman. A mired sense of possibility and age which is just beyond reach.

Grandmother lives in a duplex which was converted into a large scoping, single-family residence surrounded by a stone wall and guarded over by an old maple tree out of which some child was always falling and breaking an arm. Her husband, my grandfather, owns a factory in a nearby industrial city. He spends much of his time there and employs much of the town. The house is a sphere in which he feels awkward, often retiring to the workbench in the basement where he can walk about silently amidst the noise of the rotors and blowers. My grandfather’s company fashions speaker boxes for Bose. The irony being that for all his silence, he built a life amplifying sound.

When he comes home—those nights, if he comes home—the two sleep in separate twin beds.

Their bedroom is as big as an amphitheatre. A large cathode ray tube television is installed like a birdcage in a bracket which hangs from the ceiling in the back corner of the room.

When I visit, Grandmother and I push the two beds together. The beds are electric. The foot and the head operate independently. We each have our own personal remotes with which to operate our respective inclines.

One of Grandma’s many curatorial projects is the large candy bowl, which we pass between us. Whitman’s Samplers and Whoppers and Andes mints. We pop bonbons and sift through the dioramas on the inside covers of the chocolate boxes and watch reruns of I Love Lucy on Nick at Night. She loves Lucille Ball.

My mother keeps a photograph of my grandmother where she found us in bed together one morning, the candy bowl between us. Grandma’s large rose-tinted glasses hang off her face. Next to her are visible a shock of my curls and my foot where it protrudes from the side of the bed.

*

By her criteria, she was herself a lover rather than a wife.

—Arthur Danto on Susan Sontag

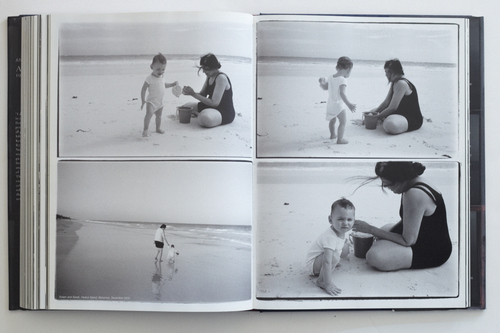

Photograph: Susan and Sarah. Harbor Island, Bahamas. December 2002. The idea for Leibovitz’s book and museum retrospective was initially Susan’s, before the end of her life. As I scan the black and white portraits of her lining the walls, I wonder whether she wanted a say in how her own life would be curated after she’d gone. Perhaps this is the highest vanity for which we all yearn. And yet upon entering the gallery at the Brooklyn Museum, the immediate impression is that the photographs are undeniably Leibovitz’s— Demi Moore’s pregnancy, Johnny Depp and Kate Moss, Presidents Clinton and Bush, Nelson Mandela, Bill Gates, Jack Nicholson standing on a golf course, a cigarette in his lips and a golf club in hand.

However, the arrangement of the exhibit is unquestionably Sontag’s. The gallery radiates a haunting reification of her aesthetic alive in the flesh, the desire she found inherent in multiplicity, her sense of reality as “plural, fascinating, and up for grabs.”[7] The show is comprised of an unabashed mixture of public and private, fashion photography and family photographs, the glossy faces of Vogue and the intimate photos of Sontag in Venice, Sarajevo and Berlin. So, too, one encounters the trajectory of Leibovitz and Sontag’s shared private spaces, the evolution and brief merging of their various individual artistic projects, and their gravitation toward capturing what Cartier-Bresson called “the decisive moment.”

As I peruse the photographs of Susan with Leibovitz’s child, Sarah, it comes to me quite suddenly that Sontag’s own partnership with Leibovitz was a private foreshadowing of what was to become a public idea; the extendedness of their family (Leibovitz’s children, their various families, friends and cultural acquaintances) strikes me as a fitting blueprint for the family unit of the next generation. In her own frustrated way, Sontag was leading the feminist band.

Memory: Latham, NY. 1987. Grandmother has aged and is beset with forgetfulness. One afternoon she gets into a cab dressed from the waist down in nothing but stockings and her lacy, white underslip.

“Hazel?” the driver asks.

“What, Love?” she replies. (Her father was Irish. He taught her to call people “Love.”)

“I think you forgot something important.”

“What?” she says, reaching up toward her head. “Don’t I have on my hat?”

Like Sontag, Grandmother was an emotional activist. She believed in purging the soul in loud flashy hats, in living as loud as one pleased to. She walked her dog each morning dressed in my Grandfather’s thermal long underwear, a thin Lycra slip, a pink cashmere cardigan, a blue coat with football like shoulder pads and a rabbit fur cap. For her time, she was an embodiment of the transgression of Camp.

*

Language is a virus.

—William Burroughs

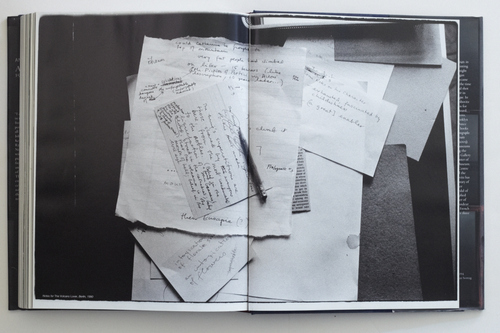

Photograph: Notes for the Volcano Lover, Berlin, 1990. Sontag once said, “The photographer’s approach—like that of the collector—is unsystematic, indeed anti-systematic.”[8] To Sontag, photography indeed developed out of the Whitmanesque landscape, the belief that “America, that surreal county, is full of found objects. Our junk has become art. Our junk has become history.”[9]

Sontag was a virulent seer. She had an almost telepathic intuition for the development of the aesthetic, in art, in literature and in culture then and now. One of her many great predictions was of the importance of the Found Art movement and its impact on literature—a medium often left out of discussion of object trouvé—as well as its resonance as part of the Surrealist vision.

Leibovitz’s photograph of Susan’s notes for The Volcano Lover prickles with Sontag’s posthumous hand. “Some Notes on his character,” reads a small index card sticking out to the left of Sontag’s pile of notes; “exhausted, fascinated by childishness.” On the next line appear the words, “(a great) enabler.”

Another small note card in Sontag’s pile reads, “An intoxication of flowers.” In the lower right-hand corner of the card the word “impregnable” is crossed out. A large scrap of notebook paper in the center of the pile contains several notes on Dickens: “On litter—15 hearers (like Mr. Pickles of Portici in Dickens) could Catherine be brought to the top of the mountain?” At the bottom of the page appear the words, “Them Eusapia (?).”

As I scan Leibovitz’s photograph of Sontag’s notes, I am reminded of what was, in some respects, Sontag’s own Surrealist vision, her insistence that American consciousness was built on the ad hoc. In her essay on Nathalie Sarraute and the novel, Sontag once said, “Art is the army by which human sensibility advances implacably into the future.”[10]

If language is a virus, Sontag was infected by it.

Those who knew her were sick with her vision.

Memory: Sterling, Massachusetts. 1984. My parents drop me off at the neighbor’s house on their way to the hospital. Mother is carrying the small suitcase she’d prepared some weeks earlier. Our neighbor, Bill, waves to Father as he backs the car out of his drive. “Say hi to Sam,” Bill calls to my parents from his front porch. “A boy!” I’d heard Father announce while listening to Mother’s stomach. (My sister is born later that evening, blonde, blue-eyed and radiant. She could have won pageants.)

The next day, Grandmother comes to stay with me in our small cape in rural Massachusetts. We play with the dollhouse my mother purchased for me when she knew the new baby was on the way. The dollhouse is painted and wooden. I regard it with mild interest from the corner of my room from time to time. Sensing my hesitation, Grandmother pulls out a pack of gum from her pocketbook. (She always carried at least one package of Wrigley’s Doublemint Gum when she traveled.) We unwrap several sticks of the gum and fashion the silver foil wrappers into doll blankets.

(My Grandmother, too, was a great enabler, fascinated by the escape provided by imagination and childishness.)

Through the plastic windows at the front of the dollhouse, the small foil blankets look like flame guards thrown on a blaze.

Memory: Sterling, Massachusetts. 1982. This memory is not my own. (I was two when it happened.) But I have heard the story so many times that I can almost picture the scene: My grandmother and mother are sitting around the kitchen table, listening to Elvis. They dig out an old tape recorder and record themselves singing, “Ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog.”

Memory: Latham, New York. 1990. Grandma and I are dancing in her kitchen. The morning has barely broken. Even Boy is asleep on his rug. Marlow Thomas’s “Free To Be You And Me” is playing on the cassette. (I can still hear Mel Brook’s voice pontificating on the difference between the sexes. “Boys are bald. Girls have hair,” the song said. It was simpler back then.)

That winter, I decide to start a newspaper. Mother takes me to the library where I photocopy stories and recipes and other things I have written out. I send the photocopies in envelopes to family members and anyone I know.

My first story features dancing in my Grandmother’s kitchen.

To me, this is the news.

*

Beauty will be convulsive, or it will not be at all.

André Breton

I am reminded of Sontag’s damning of literature’s employment of illness as metaphor. “Cancer is a demonic pregnancy…a disease of middle-class life…the overnourished, unable to eat.”[11]

Sontag was right. Pain is neither demonic, nor overfed.

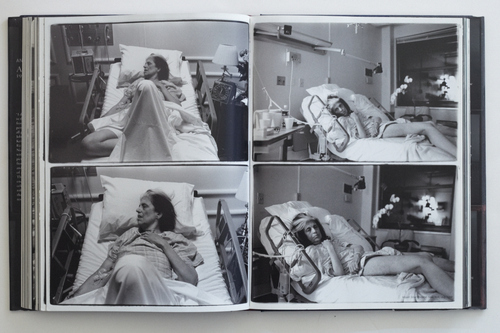

Photograph: Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, July 1998. Sontag lies on her side in a hospital. She is perched in an electric bed with the Hill-Rom insignia. (This must be its maker.) A nurse stands behind Sontag, injecting her rear.

Memory: Latham, NY. 1992. Grandma is standing in her kitchen. I hand her a copy of my paper. She struggles to pronounce the title. The words are too long. Her stroke took away her ability to formulate language.

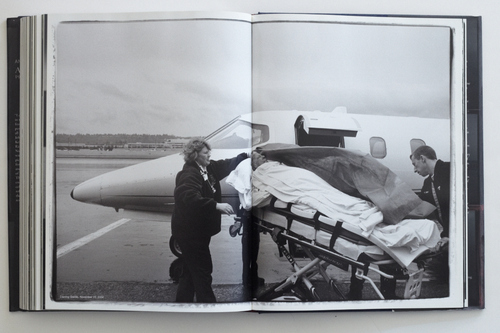

Photograph: Leaving Seattle, November 15, 2004. Susan’s body unconscious on a stretcher. Her hair is short and white. The attendants cover her with a sheet. Leibovitz borrows a friend’s plane to transport Susan to the Fred Hutchinson Research Center in Seattle where she receives a bone marrow transplant which eventually fails.

Memory: Latham, NY. 1993. Grandma asleep in a hospital. She is lying in an electric bed like the one we’ve operated together in her bedroom. When I come into the hospital room, she says, “Hello, Love.”

I bring the candy bowl and am quickly shuffled out of the room.

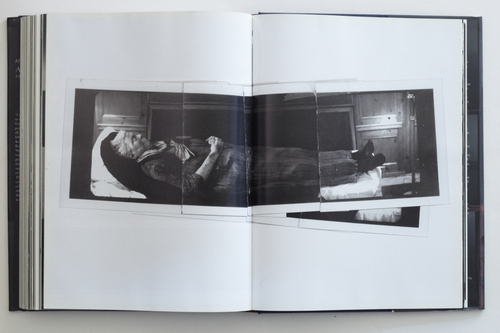

Photograph: Annie Leibovitz. New York, December 29, 2004. Susan laid out in Frank Campbell’s funeral home. She wears a dress she purchased with Leibovitz in Milan. “[The dress] is an homage to Fortuny, made the way he made them, with pleated material. Susan had a gold one and a green blue-one. She had been sick on and off for several years, in the hospital for months,”[12] reads Leibovitz’s voice on the placard aside the photograph.

Of Sontag’s illness and eventual death Leibovitz says, “It’s humiliating. You lose yourself. And she loved to dress up. I brought scarves we had bought in Venice, and a black velvet Yeolee coat that she wore to the theatre. I was in a trance when I took the pictures of her lying there.”[13]

Leibovitz captured Sontag’s deceased body in segments. The final picture has been pieced together—a composite of individual photographs of head, hands, torso and feet. The edges of the photographs are jagged and overlap slightly. Sontag’s body appears distorted. I am reminded of Sontag’s understanding of what she termed “the Whitmanesque imperative;” “Treat all moments of equal consequence.”[14] The body after death is perhaps Surrealism’s great claim that experience is not whole.

Memory: Grandma’s funeral. September 2, 1993. New Paltz, NY. Grandma is wearing her large butterfly-shaped glasses with the pink and blue tint to the lens. I am reminded of standing in her downstairs bathroom, spraying Aqua Net on her bangs, of the pink plastic comb she kept in a box over the sink.

I look over the rim of the coffin. There is little evidence of the cancer which trespassed into her life those last six months. The pink sweater she used to wear while walking the dog is draped across her shoulder, as if to say she might still catch a cold.

As I leave the gallery on my last trip to Brooklyn, I am reminded of what James Elkins terms “the drama of the eyes” in his opening essay from his collection, The Object Stares Back: “Still, this daily drama of the eyes, which foreshadows the darkness of old age, is only a minuscule portion of the daily ration of sight…vision, I think, is more like the moments of anxious squinting than the years of effortless seeing. Looking at the world is not a matter of raising the eyelids and turning the eyes in their sockets; or, to say it more exactly, that idea is a lie we tell in order to make sense of ourselves…The first thing to be said is that this informal notion of just looking will not do, since the eyes never merely accept light. Instead there is a force to the light; it pushes its way into our eyes; and conversely, there is a force to the eyes: they push their way into the world.”[15] I wonder if this is perhaps what Sontag meant when she identified dying as another mode of life: Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship.[16]

[1] Susan Sontag, On Photography, (New York, NY: Picador, 2001), 65.

[2] Ibid, 27.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Hal Foster, “A Readers Guide,” Artforum, March (2005): 191.

[5] Sontag, On Photography, 175.

[6] Annie Leibovitz, A Photographer’s Life: 1990-2005, ( New York, NY: Random House, 2006).

[7] Sontag, On Photography, 110.

[8] Sontag, On Photography, 77.

[9] Sontag, On Photography, 37.

[10] Susan Sontag, “Nathalie Sarraute and the novel” in Against Interpretation and Other Essays, (New York, NY: Picador, 2001), 100.

[11] Susan Sontag, Illness aAs Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors, (New York, NY: Picador, 2001), 15.

[12] Leibovitz, 29.

[13] Leibovitz, 29.

[14] Sontag, On Photography, 37.

[15] James Elkins, “Just Looking,” in The Object Stares Back: On The Nature of Seeing, (New York, NY: Mariner Books 1997),18.

[16] Sontag, Illness As Metaphor, 3.