An Interview with Tintype Photographer Josh Wool

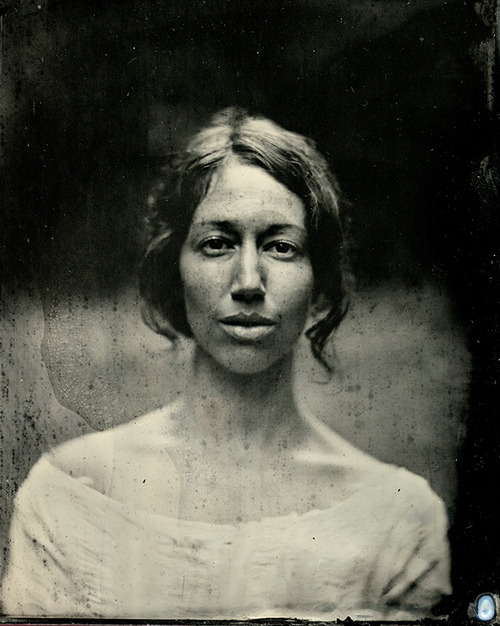

I first came upon Josh Wool’s work last year while researching a piece on the passing of Phillip Seymour Hoffman. Wool had processed one of the last images captured of Hoffman at Sundance, a grainy black and white tintype of the actor shot by Victoria Will. There was something deeply haunting about the image, a kind of strange foreshadowing of the end of an internal war. As Wool’s recent bio for the Visual Supply Company states plainly, “With an honest approach to documenting his subjects, Josh captures intimate, up-close moments. His portraiture puts the viewer right in the room with his subject and conjures a desire to understand their story.”

I heard from Wool again this past summer. I had recently moved to Lake Hill, a small rural community in the Catskills when Wool contacted me about doing a shoot for a project on artists and writers who had escaped the mélange of the city for the artistic life up north. I was honored to sit for him as one of his subjects.

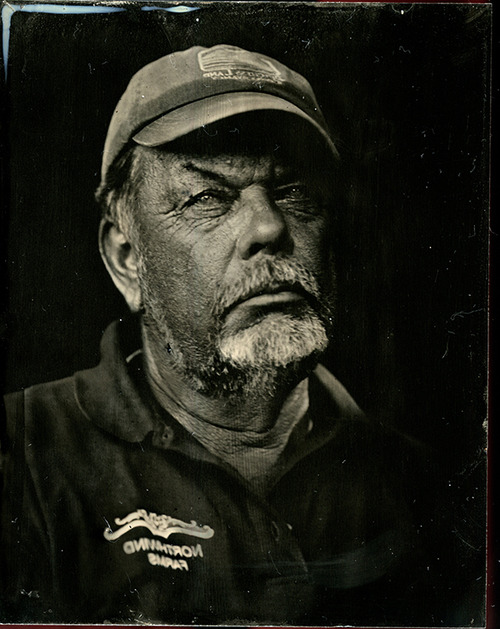

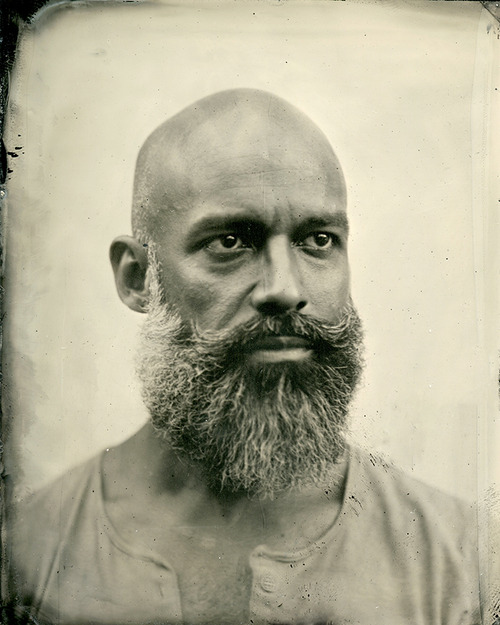

The evening of our shoot, a heavy rain descended upon the mountain. Afforded some time indoors, Wool and I took refuge in conversation and a pair of margaritas. Shut away until the sky cleared, we discussed the role of the south in Wool’s work, how he first came to photography after his career as a cook in the kitchen and reclaiming the intricate process of tintype photography—an age old trade. The next day was glorious. I sat out under the maple tree in a straight backed folding chair, while Wool captured the above image. I’ve always been shy about being photographed, but I think the image speaks to Wool’s talent—his ability to see the deeper flaws in his subjects and reveal them as strength. As we stood together in the August heat, working out of the traveling dark room which Wool creates in the trunk of his car, smelling the strange smell of processing chemicals, I had the pleasure of watching one of Wool’s images come to life. I hardly recognized myself. He had captured my life in a moment of great transition.

—Ann DeWitt

I. The South & The Purity of The Flawed

THE BELIEVER: Do you feel like the south plays a role in your work?

JOSH WOOL: A little bit. There’s definitely that southern, gothic sort feel to some of it.

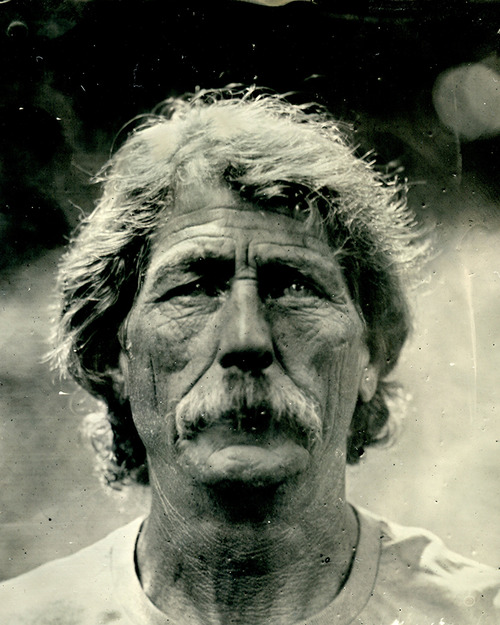

BLVR: There’s a real purity in a lot of the people who you choose to photograph. But there are others that are flawed, too. Which is what I respond to in a lot of your portraits. There’s something vulnerable about everybody.

JW: That’s what I enjoy most. Growing up in the south there is that very proper society kind of thing. But there’s also, just below the surface, this really dark underbelly. For me beauty is in the flaws.

BLVR: Same here.

JW: I’m still figuring out a style and figuring out how I want to shoot. It’s always evolving.

BLVR: When I think about creating characters with writing, I always tell students you have to think not necessarily what peoples’ flaws are, but about what their wall is, you know? What are their parameters, what can’t they work beyond? If you can get that down, you’ve got a character, basically. Either that or what they’re an expert in, what they’re neurotic about.

I feel like that comes through in a lot of your photos, which is hard because you don’t have language to translate for people when you’re a photographer.

JW: For me, a portrait session would basically be like this: we’d sit down, have a conversation, and I’d just happen to be taking pictures. I don’t use a lot of strobe or artificial light, it’s less distracting. If a job calls for it, that’s fine, but the less distractions the better. When I get in front of the camera and there are a bunch of flashes going off, I sort of want to back up into a corner.

It’s interesting to shoot people you don’t know beforehand. You have to break down the wall fast. And then there’s a different wall with people who you know, because they have a different idea of you. Sometimes it’s too relaxed.

BLVR: Do you walk into a room and know where you’re going to shoot somebody or what the setting is?

JW: It depends. I shoot at my place a lot so I know the light.

BLVR: You’ve got your palette.

JW: Yes. There are certain color palettes that I like and more of it’s about the light and matching the light to the person. You don’t want to do really hard light on somebody who’s got a rounded face. And then people who have more angular, rugged faces—harder light is going to make them appear a bit more dramatic.

But I always had an idea in my head of how I want a picture to look. I’m always striving to get there. It doesn’t happen all the time.

II. A Dark Room in the Back of Your Car

BLVR: How did you get into tintypes? Were you more interested in the process or the result?

JW: The result is definitely part of it. And the fact that all these films are disappearing and you can easily buy everything to make tintypes off the Internet. The materials are all used in a million other things so you can get ahold of them.

BLVR: And then you just construct a portable darkroom in the back of your car like we did today?

JW: Or in your house, or whatever. I saw Sally Mann’s work a couple years ago, and I studied history in college.

BLVR: I was just going to ask, were you fine art, or?

JW: No. I actually never finished college.

BLVR: More and more people I know who are really successful never seem to have.

JW: I got really bored. My first year in college was like being back in high school again. It was all the same classes. I felt like it was a waste of time and money, especially not knowing what I wanted to do.

BLVR: I was talking to a young man who works in the barn today and he was saying, “You know, I went for a year and didn’t know what I wanted to do, why go?” It’s hard because I teach in the college system and I feel so torn about it. I completely understand where he’s coming form. I have always believed that the cost of education is the biggest element that keeps the class system in America so tightly set. It keeps the 1% up there and doesn’t account for the other 99% of us. Which I loathe. And yet I teach in it. If you have four kids and it’s sixty-thousand dollars a year to go to school, how? How does that happen? I think about that now as I think about having my own children and whether or not I legitimately afford to educate them, even as an educator myself.

JW: You’ll be in debt for the rest of your life.

BLVR: Right, or you just period can’t. The young man in the barn was saying, “I don’t know what I want to do. And I said, “You know that’s the biggest thing. You need to find your passion first and then figure it out.”

There’s a great quote I always think back to that essentially says, “It’s the second thing in life you think you’re going to do that you end up being successful at. The first thing is always the thing that you put so much pressure on. You think: “I’m going to be a chef.” Or, “I’m going to be a writer.” Then it’s what you pursue without allowing for the idea to possess you—one of your other passions—where you actually might find your success. I’ve got this weird hobby on the side where I collect medium format cameras. Then you think, “Maybe I’ll become a photographer…”

JW: Yeah. I used to pour through magazines, I always liked photography and I was always interested in it. I would buy a little camera and I’d lose it or I’d break it. I was so busy, I was working sixty, seventy, eighty hours a week in a restaurant so I just didn’t have time.

Then, I met a couple of guys a year or two ago who were just getting into it and had a couple of portraits taken, and as I saw the process I said, “This is amazing.” I didn’t know that it was still really a viable thing. And then I had fallen in love with Edward Curtis photos. Are you familiar with those at all?

BLVR: Yes.

JW: It was like twenty-five volumes of Native Americans. To go back now and to think that they’re doing basically what I’m doing but on a horse and wagon. They’re shooting on 11×14 glass plates, and they have to transport that and transport all the chemicals and to do it in the field and then they’re all so good. I think the average success rate for that stuff was like thirty to forty percent for really good ones.

BLVR: Exactly. How many do you shoot of each subject?

JW: Depends. Sometimes one. Sometimes two or three. I’ve been having some issues with the chemistry, so I’ve had to retake a couple here and there. On a new day, you always have to take one or two to kind of meter it, because there’s no way to meter any of it so you have to just sort of take one or two and see how it turns out. I’ve generally been doing around three to four second exposures for most of the trip so far, but it’s fairly consistent.

BLVR: Is process cost prohibitive? How much does it cost to make one wet plate?

JW: The initial cost is what took me awhile. After that you can get pretty much any camera you can fit a plate into, so it doesn’t really matter. I figure it costs me about five dollars a shot, which isn’t bad.

BLVR: No, that’s not bad.

JW: But once you get everything together, the more you shoot the less it costs. There’s a little cottage industry that’s popped up for this kind of stuff. A guy in Maine makes all the silver bath supplies for sensitizing the plates. He makes those out of Plexiglas and he’ll cut plates to size. I thought, well, I need around five hundred plates, so I’m just going to call a metal shop. So I bought a couple sheets and they cut it for me, which cut the cost in half. There are ways to get around it.

BLVR: You have to know how to scope for it and be enterprising.

JW: And modern UV coated lenses slow it down even more, so I sourced out the lens I have. It’s from 1884.

BLVR: Where did you find it?

JW: eBay. There’s a guy up near Ithaca, the guy who kind of started everything. He spent like eight or nine years traveling the country in a horse-drawn wagon doing traveling tintype photography.

BLVR: Is there a documentary on this person?

JW: Yeah there is. There have been a couple. He’s been on some major news programs like 60 Minutes.

BLVR: What’s his name?

JW: John Coffer. He’s a really interesting guy, but he sort of lives in the 1800s. He has a cabin that he built from trees that he felled. Kind of awesome but a little extreme, I think. You can’t email him. Or, you can email him but it goes to a friend of his and the friend prints the email out and drives it over to him. It’s faster just to send him a letter. He does a couple of workshops every year.

BLVR: Actually the editor that I work with pretty closely works the same way. You have to send everything snail mail. She’ll occasionally answer personal emails but you can’t send her a word doc that’s got tracked changes or something. That is one of the things that I really cherish about working with her. It adds to the process. We actually had to put up a mailbox after we moved here.

We had to wait for a week for the mail to get forwarded and we didn’t think it was coming. And then, first thing, after we get this huge white mailbox from the hardware store in town, a little white envelope from my editor arrives saying, “Here’s your edits to the next excerpt to your novel,” handwritten and everything.

I thought, “This place is going to be magic if this is the first thing I’m receiving!” I thought honestly, “I’m never leaving!” This didn’t happen in Brooklyn, ever. [Laughs]

JW: Exactly. You can’t rush. I feel that way with photography. Everything is too fast right now which is the big draw for me to tintypes. It’s slow and takes time. I do jobs where people want the photos the next day, and I think, “I can’t.” I’ll do it, but it’s not fun.

III. The Hudson Valley & Santa’s Little Farm

BLVR: What made you think about shooting in the Hudson Valley? Do you feel like there’s a resonance with the south here?

JW: A little bit. It definitely reminds me of South Carolina in a lot of ways, and even Tennessee. I have some friends who are out in Woodridge, on the west side of the valley at the base of the Catskills, and one friend has a clothing company. She makes knit or crochet bikinis, you know like fashion bikinis, they’ve been on the cover of Sports Illustrated. She also does angora. She’s got thirty or more rabbits and sheep and goats and chickens—a Santa’s little farm type setup.

BLVR: Where is it again?

JW: Woodridge, it’s six miles from Monticello. It’s about the same distance from the city as here. Just sort of North West instead of north. It’s only twenty minutes from Pennsylvania, actually.

BLVR: It’s always inspiring when you hear about people who actually got out and constructed their own enterprise and made it creative, but also survived on it too.

JW: Her boyfriend is a recording engineer and he bought the house ten years ago and they’ve slowly renovated it. They built a recording studio there. It’s not huge but they started out with just two bungalows on the property and they do AirBnB. They built a geodesic dome last year and they have a little pond and they just put an airstream trailer on the property.

BLVR: If we ever did buy something up here—straight to god’s ear from my mouth —there is going to be a shack in the back and there’s going to be a bed that you can rent in that shack because people are making so much money off of that.

JW: Exactly. They just bought the house next door so they’ve got twenty acres now. It’s this nice little compound. When I was up there Yeasayer was recording for five weeks.

There’s a whole community of people that are in that area who are farmers and other craftspeople and she’s got a team of girls who help her make everything. There’s eight or ten people in this little community. They all hang out and they’ve really carved out a niche for themselves. I’ve always wanted to do something like that.

BLVR: Me too. I have so many friends who keep saying, let’s just start a school. I feel like a lot of the artists that we think of coming out of the sixties and seventies went to Black Mountain College, places that were actually founded by the artists living somewhere who just thought, “Okay, we’re going to teach people to make their craft.”

I just had an experience teaching at an art school in the city where they’re using the “artists as mentor” model, hiring working writers and artists. It’s a system of permanent adjuncts. If you’re there for four years, supposedly according to the union, they keep you and provide health insurance and that kind of thing. It’s an odd system when you think about it, because the kids who come in are paying forty-five to fifty-thousand dollars a year to go there. As an adjunct there you’re making forty-five hundred dollars a class. You’re still just getting paid by the class and, maybe, getting health insurance if you’re lucky.

It’s bizarre because why not just start a full-time school with a bunch of practitioners who think, “Okay, I’m a sculptor, I’m a photographer, I’m a pianist, I’m a whatever,“ and have people come?

I don’t think those days are over yet. I hope they’re not.

JW: I hope they’re not. There’s that tradition, especially in rural places, of oral histories, and oral stories that get passed down through generations and evolve from generation to generation.

BLVR: You know there’s a cool guy right up the road. We were trying to buy a used grill when we first moved here. If you just go up 212 that way a little bit, right when you go into Willow, you see that sign. It just says, “Sale.” The guy runs garage sales on the weekends. He lives in an old abandoned white church, just up on the right. I think he may have been a photographer of some kind but he lives in this kind of makeshift shack in back that he used to run a photo gallery out of.

JW: Wow. There’s an old guy in my neighborhood and he looks like he’s out of another, completely different time. Very European, eastern European looking. He’s got one big bulging eye and looks like a cartoon character. He’s probably in his 50s. But he wears this sailor cap with a captain’s hat, and has a chin beard that’s really long. He’s such an interesting looking guy, I have to snag him at some point.

BLVR: I love people that literally wear their heart on their sleeve, where it’s all there physically. All of those flaws are just externalized in some way, whereas everybody else works so hard to kind of keep those things on the inside.

IV. On Process: You Can’t Rush & “There’s Always Cooking Steaks”

BLVR: I was in Berlin by myself last winter. I don’t know why, but that city’s always been very attractive to me and I always wanted to go. It has that kind of dark, neurotic energy about it.

JW: It’s sort of like that in New York, as far as art goes.

BLVR: Totally. A woman I teach with who does art history had a friend who lived in Berlin. When I arrived he emailed and said, “Come over for tea and we’ll go out or do whatever.” I got there and it seemed to me he and his roommate lived in a palatial loft with beautiful floors and crazy molding. We were talking about working and how to support yourself as an emerging writer or artist in Berlin verses America. He said, “Why don’t writers in America just get a grant?” And I said, “That doesn’t really exist.” I was telling him over tea about a friend of a friend, an emerging artist, who receives twenty-two thousand euros from the German government just to make art.

JW: Wow, that doesn’t really happen here. [Laughs]

BLVR: No! [Laughs] I said, a grant from who? The NEA? I mean that’s next to impossible.

JW: Moving to New York was a really strange experience for me because I moved there when I was thirty-four and I had come from a really successful career where I had lived in a two thousand square foot loft in Tennessee.

BLVR: Wow, what were you making as a chef?

JW: Like six figures, or close to it.

BLVR: So who were you cooking for, fancy restaurants?

JW: Yeah, sort of. The last place was a big steakhouse which was not my favorite. But, it was big and it was busy and we did six or seven million dollars a year in sales. It was always busy.

BLVR: [Laughs] People need their steak. Or, so I’m told.

JW: Yeah and a lot of convention business. But it was a big transition for me going from a very comfortable lifestyle for many years to quitting that and not making any money for the last two years. It’s been such a huge adjustment. I really like it in some ways, then other times I think, “I’m going to be forty soon.”

BLVR: Right, that’s the crisis of our generation, now everybody’s saying the same thing.

JW: I don’t want to have roommates anymore unless it’s someone I’m in a relationship with. I hadn’t had roommates for years other than girlfriends and now I’m living with four other people. It’s fine but I can’t do it for long term.

BLVR: It strikes me that this is the thing our mid to late 30s crowd is going through, where we think, “Okay, we’ve made this choice to live outside the lines. We’re doing this particular thing. But these lifestyles that seemed approachable or nearly approachable for maybe our parent’s generation or even people that were ten years older than us rather aren’t anymore. It’s a different world. It’s a different place. Everyone’s in massive debt from school and mortgages are impossible to get and inflation is such that I feel like people don’t make any more money for doing the jobs that they do but the cost of living has gotten so ridiculously expensive. You can’t dream of having the baby boomer lifestyle that our parent’s generation could have.”

JW: The idea of buying a place to me is really scary. I’ve never been in any one place in my adult life for more than three or four years.

BLVR: Yeah I’m totally the same. The idea of putting down roots somewhere seems almost unfathomable.

JW: It’s a tradeoff, you either pay rent and have mobility or you buy and you stay put for a while. It depends on which side of the fence you want to be on. I mean, for me I need to be around people because that’s what my work is about and I need social interaction. I think it might be tough for me right now to move out to someplace like this and do it on my own, without having some sort of support network of some sort.

For me I just want a bus. I just want a small, little cottage, and then an apartment studio of some sort, some place where I can set up a real studio and actually do my work, and be close enough to the city where if I need to go in for a commercial job I can go. I still have some money to make before I can move.

BLVR: There’s always cooking steaks.

JW: I’ve been having conversations like this with a lot of people recently and a big part of this grant trip for me was not so much just the farmers or artists or creative but the small communities and people carving a niche out. It’s just escaping the whole rat race. It’s almost counter-culture.

BLVR: Yeah, that old photographer who lives in a abandoned church up the street, I ended up talking to him for a while. And he was like, “You know what? It takes a commitment to live up here.” I agree. It’s just far enough that it’s not like you can take the train to work everyday. It doesn’t feel like you just live in Williamsburg or something.

When I go into the city for something I tend to do everything all at once. It’s the first time in my life where I honestly have a place where I live and I think, “I want to come home.”

You look around and think, “Okay, it’s a house.” And somehow that made me nervous. All my friends kept saying, “What happened to you, did you fall off the grid?” And I just say, “I’m actually so happy. I wake up at 7:30 every day and jump out of bed because I just want to go and do all the stuff that you can do around here. I want to do my damn laundry myself, not at the laundry mat.”