“IT’S THE STORY YOU ENTER, NOT THE CHARACTER.”

An Interview with Aimee Bender About Her Syllabus

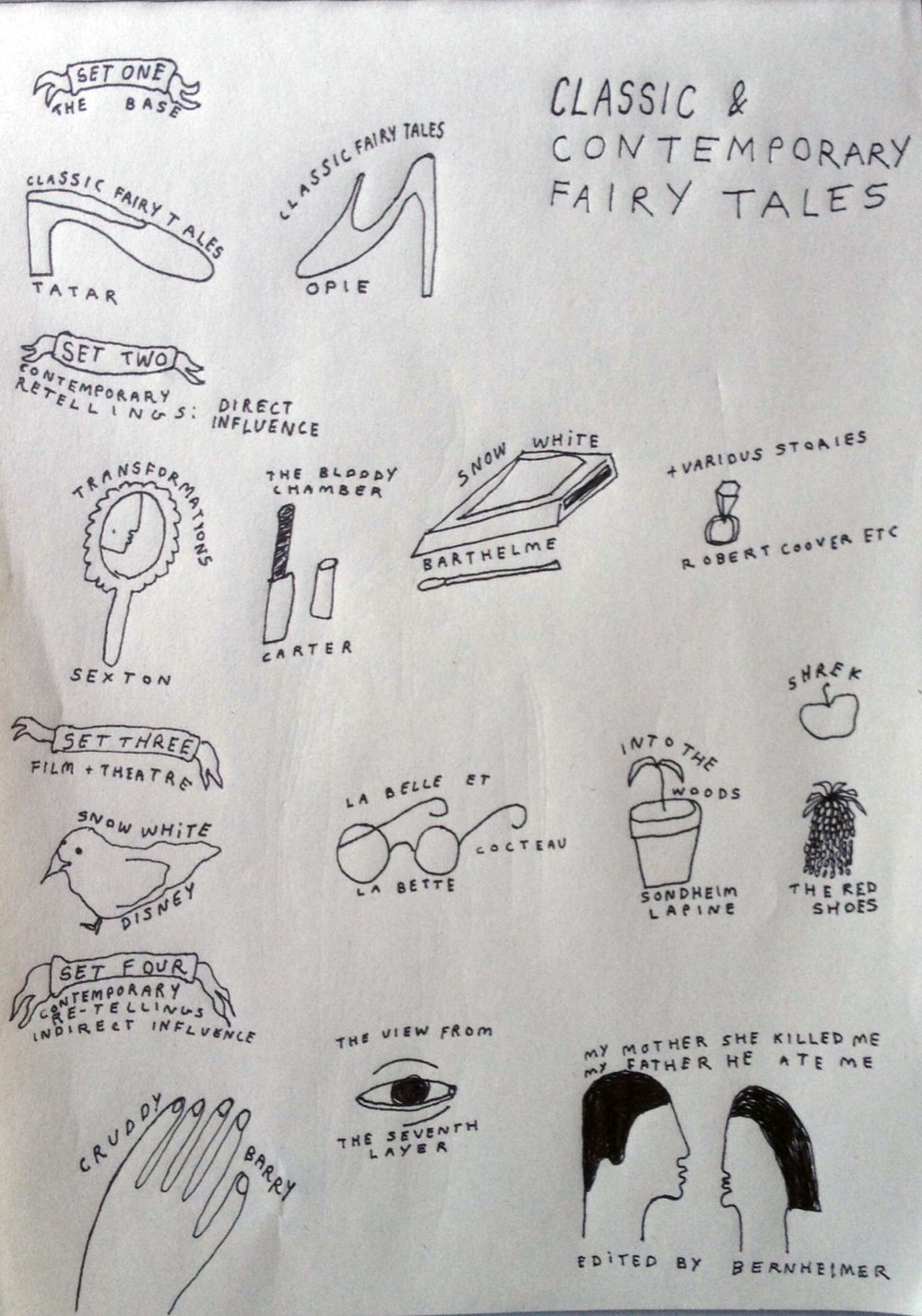

This is part of a series of conversations with writers who teach, where we discuss how they develop an idea for a course, generate a syllabus, and conduct a class. Read the full syllabus here.

Aimee Bender is the author of The Girl in the Flammable Skirt, Willful Creatures, and The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake. Her most recent short story collection, The Color Master, includes two retellings of fairy tales. Her work has been published in The Paris Review, Harper’s, and Granta, among other places. She teaches at the University of Southern California.

—Stephanie Palumbo

I. THE ECONOMY OF THE TALE

STEPHANIE PALUMBO: Tell me about the background of this class.

AIMEE BENDER: I’ve only taught this as an undergraduate class, and the people that have taken it are not necessarily English majors—they’re science, pre-med, communications. It’s changing now, but the general education program had a template of things you had to include in a class: a certain amount of writing, emphasis on critical thinking, and pages of reading per week. You got to take those factors and stir them in a pot and come up with an idea. I knew I would naturally lean toward doing something with fairy tales. They’re perfect little nuggets to talk about.

SP: So many books have been influenced by fairy tales. How did you narrow down the reading list?

AB: I split it into two halves. One part was direct influence: stories taken from a specific tale. So for “Snow White,” we’d first discuss the tale and all different kinds of Snow Whites from various countries, then look at a new telling, like Donald Barthelme’s Snow White, which is radically different but uses the story as a base. There aren’t an endless amount of these direct retellings. The other part, which is super flexible, is indirect influence. I switch those readings a lot more, because so many things can fit. For years, we read José Saramago’s Blindness, but a lot of the students would argue that they didn’t feel it had fairy tale elements, just certain craft similarities, like very little internal reflection and characters without names. What makes a fairy tale a fairy tale is pretty debatable.

SP: How would you define a fairy tale?

AB: There are various definitions, including a great one by Bruno Bettelheim. I think fairy tales are usually quite short, have archetypes, include very little internal experience of the characters, involve an element...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in