Drawing by Jos Demme

Drawing by Jos Demme

This is the first in a series of conversations with writers who teach, where we discuss how they develop an idea for a course, generate a syllabus, and conduct a class.

Ben Marcus is the author of Notable American Women, The Age of Wire and String, and The Flame Alphabet. His most recent book, Leaving the Sea, was released in January. He has been published in Harper’s, The New Yorker, and The New York Times, among other publications, and he is the recipient of several awards, including the Whiting Writers’ Award, three Pushcart Prizes, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. Most importantly for the purposes of this interview, he taught at Brown University before joining the faculty at Columbia University, where he is currently a professor.

—Stephanie Palumbo

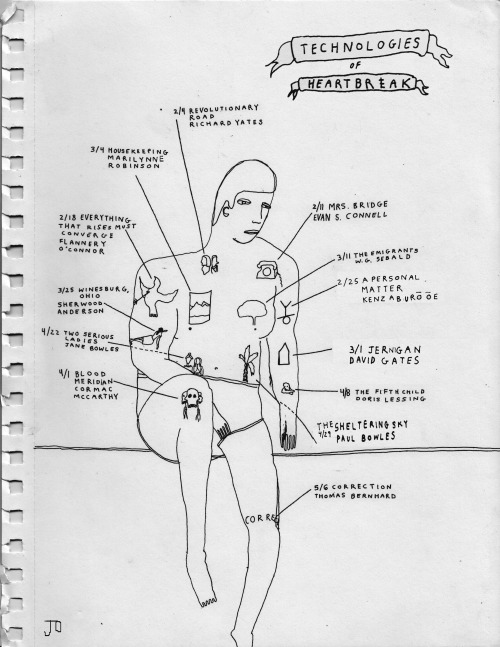

See the syllabus for Marcus’s fiction seminar, Technologies of Heartbreak.

I. A KIND OF TECHNOLOGY

STEPHANIE PALUMBO: How did you begin to design this course?

BEN MARCUS: I created this class when I first arrived at Columbia, which I think was in 2000. There are workshops, which are the standard creative writing classes, and there are seminars, and back then, there was a more open question about what you did with writers outside of a workshop. What were lit classes really for? A lot of times they would mimic an English department class, where you’d read some good books and talk about them interpretively. It seemed like there was this opening to not be tied to that format. So I thought, what did I struggle with as a writer when I was a certain age? What did I not know how to do, what was confusing, what did I not even know was a problem?

I kept returning to something that I value as a writer—creating feeling out of nothing. We open a book and within half a page, our heart is racing, there’s all kinds of biological stuff happening, there’s actual physical emotion. How is that done? In some sense, it seemed obvious that the goal of so many writers, regardless of aesthetic, is to create feeling. It is a kind of technology.

SP: Did you ever take a class like that in college?

BM: I went to an MFA program and I was perfectly happy, but I never got this kind of instruction. I had a really good course called Ancient Fictions with Robert Coover, who was a favorite teacher. We read some of the oldest fictions, including the Old Testament, Gilgamesh, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and looked at how recurrent and timeless some of their tropes are. But it wasn’t really about parsing technique.

SP: In your syllabus, you asked, “Is it impossible to isolate our reaction to a book in terms of its language?” Were you able to answer that question through this class?

BM: I think the answer is yes and no. Fiction is too complicated and too elusive to break down into a set of tricks. But making students ultra-aware that they’re in the business of creating feeling out of sentences can help. This class tries to reach into a writer’s process and push on it a little, form it, test it, and get students to ask hard questions and practice different approaches. I wanted my students to read some books that are teeming with feeling and take them apart, sentence by sentence, to try to figure out exactly how that feeling is created.

II. STRANGE, OBSCURE, CREEPY LITTLE BOOKS

SP: Is any book you love inherently instructive?

BM: When I was first teaching as an MFA student at Brown, I assigned my ten favorite books at that time, and they were strange, obscure, creepy little books. I made no effort to look at who my students were, what they’d read, and what might trigger some development in them. It took me a year or two before I realized a reading list is not my trophy case. It’s actually for others entirely.

SP: What books were on that early syllabus?

BM: Ida, a beautiful little Gertrude Stein book. And I was into the French New Novel writers, so I included Alain Robbe-Grillet’s The Voyeur. But I wasn’t enthusiastic about that when I was my students’ age, so I started to think, when I was nineteen, what would’ve ripped my head off?

SP: How did you put together this particular reading list?

BM: I was thinking of books that use different means to create great doses of feeling. Revolutionary Road is a tearjerker, a big American novel. The students might read that and feel devastated, but I don’t want them to think they have to write a big American novel. They could actually just go deep with one character and write short episodic scenelets, like Evan Connell did with the novel Mrs. Bridge.

SP: Mrs. Bridge is made up of more than one hundred brief vignettes. Compared to a traditional novel, how does that style affect the reader’s experience?

BM: Mrs. Bridge is such a beautiful, haunting book in part because each very short chapter can function as a short story. There’s a kind of completeness, compression, and sorrow that’s punched in, and something cumulative happens when you experience that many intense sorrowful moments. In Revolutionary Road, there’s a chess game to what’s going on, and it moves you in and out of feeling in broader, slower ways. Arguably, it’s a more complicated book. But in Mrs. Bridge, you get to see how in one page, the writer takes you from nothing to a very big, very devastating something, over and over and over again. That’s instructive for students—to say, actually, I don’t have any excuses, I could get this done right away. Yes, we read a book that took its time, but now we’re looking at one that’s moving fast, creating feeling very quickly out of very little.

SP: How exactly does Connell build that tension?

BM: The feeling arises out of us sensing this very well-meaning person who has a lot of love but has trouble projecting it out into the world. So there’s a lot of nice irony—we see her coming across as stilted and awkward, yet we have full access to her interior and know the depth of her love and compassion. It’s hard not to feel sympathy for someone who is so poor at being able to project all of that. The form of short episodes allows Connell to cycle through this stuff. The book is an epiphany machine. He generates them in almost every chapter. And so I think the form clearly suited him.

SP: Winesburg, Ohio is structured somewhat similarly, as a series of loosely-linked short stories, and its author Sherwood Anderson later wrote that “the true history of life is but a history of moments.” As a writer, how did he make these smaller moments cohere into a larger whole?

BM: I have a lot of students who want to write linked collections but wonder what those really are. Winesburg is the quintessential one, I think. It worked because the universe is circumscribed. He has a bounded space that he is pulling from, and there’s this nice, unexpected resonance when things return and recur. Anderson makes a series of portraits. Some are more successful than others, some are more poignant than others, but he binds his space and works within it.

III. THE NATURE OF FEELING

SP: Housekeeping began as a list of metaphors that Marilynne Robinson wrote when she was a PhD student studying language in 19th century American literature. She later returned to the list and realized there was a common thread throughout the metaphors, and she decided to turn it into a novel. But it reads very cohesively.

BM: It’s a favorite book of mine. Okay, you start out reading about a couple of girls growing up by a lake, being raised by their grandmother. Big deal, right? And yet it is. The book has this nearly bottomless sorrow. A lot of what we looked at in class was how you can take pretty basic domestic materials, the landscape, and very little action, and methodically create the conditions for something really, really devastating. You can’t just write a bad family and make everyone care. So we assessed how we come to care, how to get the reader not to take sides, and what arises in that book that captures you and doesn’t release you and subjects you to something nearly unbearable.

SP: How does Robinson create that intensity?

BM: I think it’s in her observational detail. There’s a scene where the girls are eating sandwiches, and she includes a description of one of them kicking her legs under the table. I think it’s the poetic acumen, the way the grandfather’s train goes into the lake, the way the lake is described—it’s incredible.

SP: Why did you include David Gates’ novel Jernigan on this list?

BM: Jernigan is on there because the nature of the feeling is quite, quite harsh. There’s a really abrasive main character. There’s a lot of devastation. There’s a lot of heartbreak. It’s narrated by an alcoholic protagonist, very male, very angry, hyper-articulate though, as self-damning as he is damning—a great, attractive protagonist who is his own worst enemy. In class, we looked at the psychological configuration of that book, somebody tearing everything down around him, and the behavioral trajectories that you can put into place and their consequences. It’s a great book. The Correction is also on the syllabus—that’s a much more distilled, purified version of rhetorical fury. Because the class focused on the creation of feeling, we talked about ways anger can be provocative and compelling in fiction and ways it can feel flat, limited.

SP: How does Gates make that anger seem provocative and compelling, and not unapproachable?

BM: There’s a train wreck, voyeuristic feeling that arises in Jernigan. He’s destroying himself, but he’s quite poetic and lucid about it. You’re rubbernecking a little bit. And I think a lot of fiction is asking that of us. Certainly with A Personal Matter, where a character is trying to destroy his own child—you feel like you shouldn’t even be reading this. It feels inappropriate, like it’s someone else’s secret and you found their diary. It’s a big creep out.

So what makes it work, I suppose, in Jernigan, is he’s a rake. He’s charming, even if he’s bad. And in some sense, part of his engine is love. You’re horrified and seduced by him. Whatever’s bad about him doesn’t feel simple. So often the answer to that question, in one way or another, is complexity and shading. When something gets too easily knowable, it gets less interesting.

IV. KEEPING READERS AWAY

SP: Blood Meridian is another intense book on the syllabus. How does Cormac McCarthy’s distinct, sparse writing style convey the violence of the story he’s telling?

BM: His use of language is completely tied to how you feel when you read it—it certainly seems like the delivery is all. Blood Meridian is among the most rhetorically hyperbolic of McCarthy’s books. In fact, the book that followed, All the Pretty Horses, looked like it was written by a totally different writer. Often we’re looking at work that’s a lot more stylistically mild than Blood Meridian, so what is the emotional effect when language is cycled up the register like that?

He does this recurring thing where some character spits and someone else spits, and someone says something and someone else doesn’t answer, and then he’s like, “Off in this distance, they saw two riders hanging as if by strings, like some pale marionette set adrift in a world long since cooled and died.” He’s constantly serving up the world as this mechanical, contrived, hollow place. Where everybody’s a puppet or a mannequin or skeleton, or everything’s dead or fake, and everything’s manipulated by unseen forces. We’d ask a question in class like, why describe a landscape at all? What is that ever for in fiction? Is it to be pretty? The answers are sort of obvious. At its best, it creates mood, the same way music does in a movie. But McCarthy would use those sometimes bland tools from the writer’s toolkit and make them really bleak, reminding you every time he describes the landscape how empty it is and how pointless everything is.

SP: A New York Times review of Blood Meridian said that “the brutality of his subjects may have kept readers away,” and some people have criticized Richard Yates for appearing cold toward his characters in Revolutionary Road. How does it change a book if an author seems more gentle toward his characters?

BM: It’s hard to say, because I read criticism like, “So-and-so hates his characters,” and I never quite understand. To me, I think there’s got to be a lot of compassion to create a book like Revolutionary Road. I even think Bernhard, who is essentially anti-humanity—there’s something tremendously compassionate and sympathetic in that apparatus for any of this to come out.

SP: The willingness to let characters do morally questionable things shouldn’t be equated with a lack of authorial tenderness toward them.

BM: Right, and I tend not to look at characters in that way, whether they’re likeable or not, but rather, since they’re not real, in terms of how compelled I am by them. I’m not evaluating them as potential friends—I’m evaluating them as linguistic constructs that might cause complex reactions from me.

SP: One of the last books on your list, Two Serious Ladies, has been described as bewildering, mesmerizing, and hallucinatory. How does Jane Bowles create those sensations in the reader?

BM: That’s a sort of eccentric favorite—in some ways, it may be my favorite book. It is so insane, so beautiful, and in some sense, unknowable to me. On the surface, it’s not really about much, but the arrangement of words does something chemical to me. I feel a kind of reverence and awe about the power of fiction, but that doesn’t seem to stop me from trying to think through its possibilities with my students.

Photograph by Heike Steinweg

Stephanie Palumbo is a documentary film and television producer, and a former assistant editor at O, the Oprah Magazine. She lives in Brooklyn with her boyfriend and cat. You can follow her @onetoughnun.