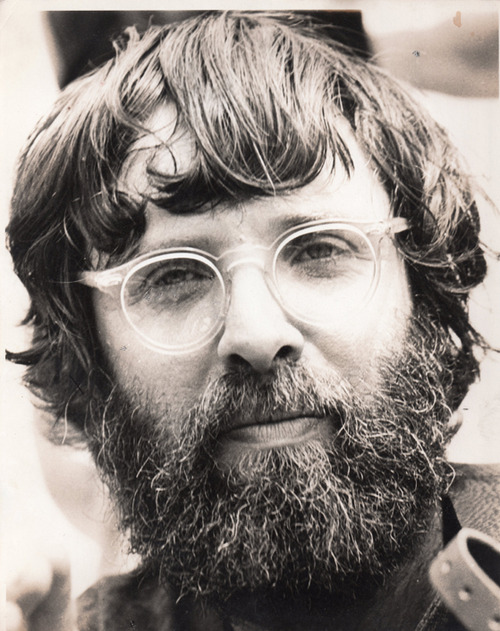

Eric von Schmidt in 1965.

An essay by Joe Boyd

While it’s true that Inside Llewyn Davis takes some of its plot from The Mayor of MacDougal Street (Elijah Wald’s book about Dave Van Ronk), the Coen Brothers never intended the character portrayed by young, skinny Oscar Isaac to bear much resemblance to gruff, burly Van Ronk. This hasn’t prevented re-evaluations of Van Ronk’s music appearing in both The New York Times and The Guardian, explaining to younger generations his importance as a folk-blues singer and an influence on the young Bob Dylan.

Before proceeding further, I’d better declare my interest. I knew Van Ronk and heard him play a number of times, but was never a fan. From my youthfully opinionated 1962 perspective, I disliked the path he laid out for younger white folk singers to butcher the blues: scratchy voice, “red-hot-mama” clichés, plunky Josh-White-influenced guitar picking.

In White Bicycles, I wrote about waking on the morning of November 22, 1963, hearing about the killing of President Kennedy and rousing Dave, who was sleeping on my couch in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His reaction was to gloat that “chickens” were “coming home to roost,” and then to turn over and go back to sleep.

Having read a good deal about the assassination since, I have to admit that whether he was referring to Kennedy’s reliance on Sam Giancana’s Cook County machine to deliver Illinois’ electoral votes or his green-lighting of the CIA’s Castro overthrow mission and then scuppering it, Dave may have actually had a point. At the time, however, his response was not endearing.

Van Ronk ended up on my sofa because, following a Boston area gig, he, along with me and my roommate Geoff Muldaur and a few other denizens of Harvard Square, had joined a poker game at the apartment of Eric von Schmidt. It had gone on too late for him to rouse his planned local hosts, so at 5am, Geoff and I offered him our sofa.

Von Schmidt was a singer and songwriter who made a number of records but has never had much of a reappraisal or revival. He resembled Van Ronk in a number of ways: Germanic-prefixed surname, beard, raspy voice, blues-ish repertoire, and father figure to a generation of young singers—including Bob Dylan. The similarity ends there. Eric was not without his dark corners, but he was a generous and open guy, a successful painter and illustrator, and he helped lead the Boston-area folk scene away from the Greenwich Village pitfalls.

I first heard him in 1960 as the opening act at a Joan Baez concert. He finished his set with a stunning rendition of Sin-Killer Griffin’s “Wasn’t That A Mighty Storm”; I felt I had experienced a completely new folk-revival aesthetic. Greenwich Village folk singers followed the example of Pete Seeger and the Weavers, who had their own party line agenda, which was to teach the world to sing each other’s songs. This admirable aim had the unfortunate effect of creating a bland, hearty style of strummed, harmonized performance that made Spanish Civil War ballads, Sea Shanties and South African miners’ songs sound as if they were part of the same canon. (Seeger’s solo work often reached genius level, but that’s another story… and teaching the world to sing “We Shall Overcome” turned out to be a pretty good idea.) Dylan’s hero Woody Guthrie had injected an edge of energetic authenticity to the New York school, so it was natural that he would gravitate to his fellow Guthrie acolytes Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and Van Ronk as he settled into the New York scene.

Eric von Schmidt on the Tom Rush Radio Show, 1960.

In Chronicles, Dylan describes the attractions of this world, but goes on to recount how he began listening to older, wilder forms of music in the Harry Smith Anthology of American Music, with its reproductions of commercial 78s from the 1920s and 30s. Before long, he was leaving the strummy protest songs of his early years behind and exploring more interesting byways of American—and British—traditions as the basis of his songwriting, as well as keeping one ear open to the Top 40.

On his first LP, Dylan includes a shout out not to Van Ronk, but to von Schmidt; and it is a von Schmidt record jacket that appears on the cover of Bringing It All Back Home. The change in Dylan’s music that climaxed with his electric performance at Newport in 1965 was closely connected to his friendship with Eric and his frequent visits to Cambridge, where he also connected with Bob Neuwirth, who was to be his loyal sidekick for many years.

In Cambridge, Dylan found a community of specialists, not generalists, who tried to replicate the tuning, fingering and subtle inflections of the classic original, rather than enveloping it in an accessible style. And, by 1963, after-hours jam sessions around Harvard Square could veer from Willie MacTell or Bill Monroe classics into numbers by those startling new songwriters from Liverpool, Lennon and McCartney. The agenda around von Schmidt and his disciples was “music for music’s sake,” with politics second. The terrible events of the morning after the poker game began the decline of political folk song; what was the point of singing for change if powerful forces were waiting to kill off any idealism that might evolve into a movement?

Dylan recorded von Schmidt’s version of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” and announced, “I first heard this from Ric von Schmidt. I met him one day in the green pastures of Harvard University.” “Follow You Down” was one of Eric’s reworkings of a traditional song. His approach was never slavishly imitative; his strong personality meant that such songs became as much a part of Eric’s musical identity as his own compositions, while maintaining a rhythmic and spiritual connection to the original.

Von Schmidt wasn’t an apolitical songwriter, but his compositions were subtly didactic, never hectoring. One of his most beautiful and moving songs, inspired by time spent painting on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent, is “Joshua Gone Barbados”, a song about a cane cutters’ union boss who betrays his workers. “Joshua gone Barbados, staying in a big hotel / People on this island, have many sad tales to tell.” Another is “Wet Birds Don’t Fly At Night”, which gently mocks Westerners’ quest for Zen enlightenment. His songs are sensual, romantic, cynical and subtle and someone should do a box set of them or a tribute album.

Von Schmidt didn’t often appear on Cambridge stages, but his presence was felt everywhere. The pin-up boy of Harvard Square folk, Tom Rush, drew most of his repertoire from songs Von Schmidt taught him. People talked reverently about how Eric would send away to Moore’s Orchid Farm in El Paso for peyote buds, cook them up on his stove and invite friends round for a transcendent evening. Bach, Lord Buckley, the Swan Silvertones and Doc Boggs would be stacked up on the record changer to provide the soundtrack for the journey.

Music was just a part of Eric’s life; he was first and foremost a visual artist. After his discharge from the army in the mid-‘50s, he won a Fulbright to study art in Florence. Back in Cambridge, he designed record covers, posters and books and painted. His father had been a “Western” artist and he maintained the family tradition by painting a mural of the Battle of Little Big Horn that now hangs in the Ulrich Museum in Wichita, Kan. His large painting of the Battle of the Alamo is on display in San Antonio.

It was always a treat to see a von Schmidt poster for a concert, or his artwork on a new LP cover, or to discover that he would make a rare appearance at Club 47. He was quiet and self-possessed but never aloof and a very funny man, with a laugh that put a smile on every face in the room.

On the Eric Sings von Schmidt LP, “Kennedy Blues” tells of going to bed that fateful night and waking to be told “they stole my man away.”

I run to the river, the river run into the sea,

When I heard the news, I felt I’d lost a part of me

The performance is heart breaking in its understatement, a deeply felt expression of what we all lost that day in Dallas. My own strongest memory—aside from Van Ronk’s comment—is of staring into the waters of the Charles River.

In Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coen brothers capture the atmosphere and look of the early-‘60s Greenwich Village folk world. The heart of the film—the drive to Chicago and back—is a brilliant set piece, startlingly reminiscent of my own treks to the Windy City during those years. My only misgiving is that we had a lot more fun than the characters in the film seem to. And the man who taught us the most about enjoying life to the full was Eric von Schmidt.

Eric von Schmidt with Joe Boyd, Tom Rush, Geoff Muldaur, Maria Muldaur and Eric Anderson at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Photo by Jim Floyd.

Eric von Schmidt backed by Dick Farina and Bob Dylan.[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lgRo5XGlgOU?list=PLinwTX9Pvnxh4M1GBnh6R1q68qLxU7Mxp]

Champagne Don’t Hurt Me Baby, Eric von Schmidt.[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3IBv3dsp8w?list=PLinwTX9Pvnxh4M1GBnh6R1q68qLxU7Mxp]

Fair and Tender Ladies, Eric von Schmidt.[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBx1TRKIWoY?list=PLinwTX9Pvnxh4M1GBnh6R1q68qLxU7Mxp]

Joe Boyd is an author, most recently of White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. He has produced records by Nick Drake, Incredible String Band, Cubanismo, Fairport Convention, REM, Pink Floyd, Ivo Papasov, and many others. He’s produced the films “Jimi Hendrix” (1974) and “Scandal” (1988) and curated a number of concerts. See more info on joeboyd.co.uk.